Hamburger Golf Club

Hamburg, Germany

Located two hours inland in Falkenstein, Hamburger Golf Club is one of Europe’s most attractive courses thanks to its the rolling topography and large areas of heather. Pictured above is the reachable par five seventeenth.

When Harry Colt took the train between the classy De Pan Golf Club in Utrechtse and Hamburg in 1929, little could he have realized how swiftly the peak of golf course architecture in Europe was coming to a close? The Great Depression in North America was about to commence and Europe itself would be torn apart a decade later. Yes, the firm of Harry Colt, Alison, & Morrison would go on to build several more courses of great distinction in Europe, most notably at Royal Hague, but by and large not only was their best work done but some of it like their seaside course at Knockke would be forever lost as a result of World War II.

Fortunately, there is a renewed appreciation today in England and across Europe for Harry Colt‘s work and Falkenstein is now widely regarded as Germany’s best course. Built during the transition from hickory to steel shafts, it was always meant to be a course for great events. Set on nearly 175 acres, there is a sense of spaciousness to Falkenstein that not all Golden Age courses enjoy. In addition, its practise area is one of the best in Europe, which is a good thing – Germans famously receive more golf lessons per golfer than do golfers in any other European country.

The raw site with which Colt had to work was ideally suited for golf thanks to its sandy soil, open nature and rolling topography.

Though the club is rightly proud of possessing a Harry Colt course, that is not to say that changes haven’t occurred to it since play commenced here in the summer of 1930. According to historian Christoph Meister,

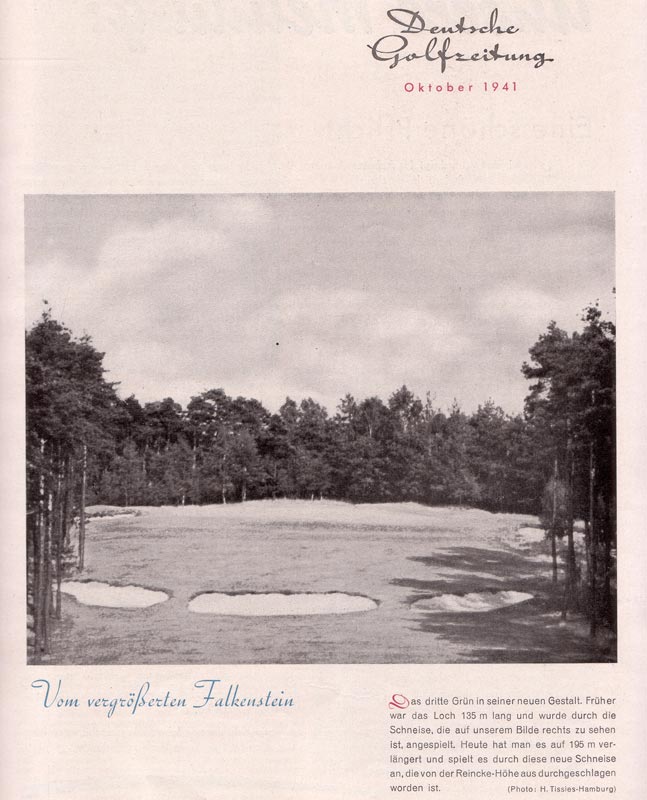

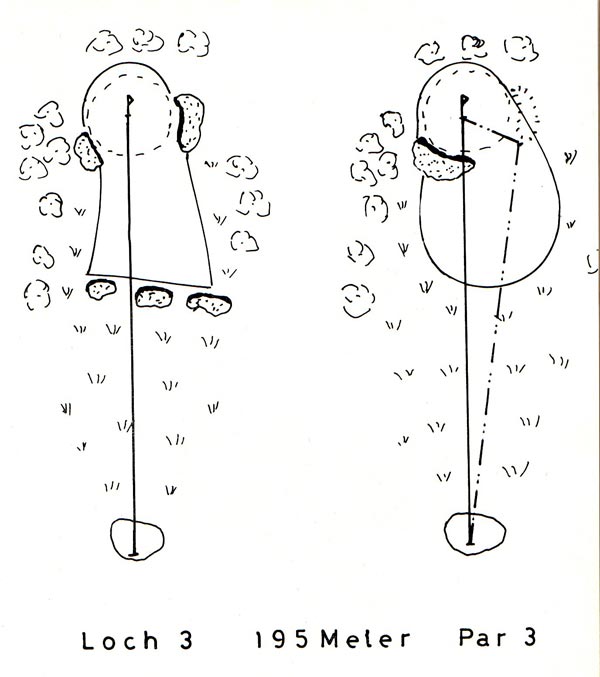

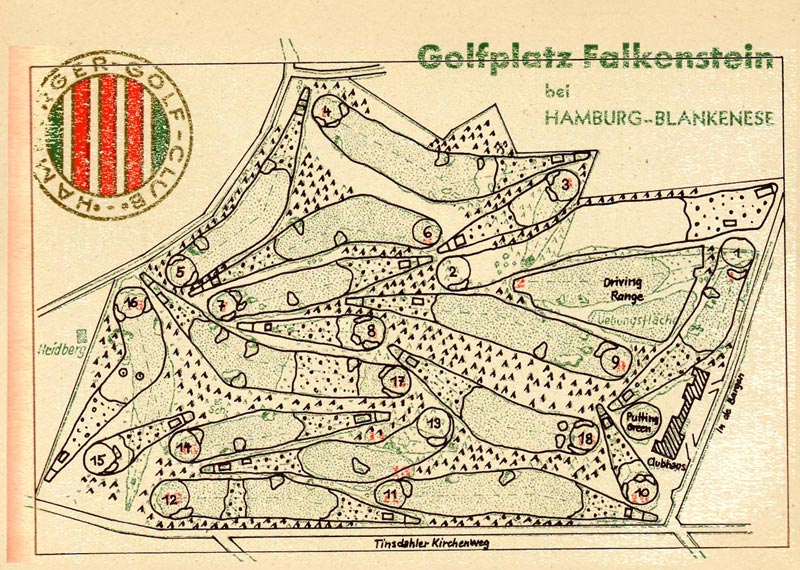

When the new Falkenstein Golf Course was officially opened on July 24th, 1930 it played 5,612m (6,137yds). Bernhard von Limburger, editor of the German Magazine “Golf†and golf course architect himself, wrote in his article covering the opening tournament that all the course was lacking was a true par-5 hole. Also with the steel shaft becoming more popular, it became evident the course could use some more length. Thus, in 1938 a major reconstruction was started to lengthen the second hole from 345m (377yds) to 500m (547yds). In addition, the third hole was lengthened from 125m (137yds) to 195m (213yds) and was accomplished by moving the tee westwards onto the “Reincke-Höheâ€, the highest point on the course. A new 3rd fairway was cut through the forest. The 3rd green was already graded towards the new teeing area so that the green only needed very little movement. A row of cross bunkers was built some 50m in front of the green. The work was done and supervised by then club manager C.A.Hellmers, who was himself a former scratch player. The author of these lines nevertheless believes that like in Frankfurt around 1937 Morrison was asked for his opinion regarding some course alterations. No.9 at Berlin-Nedlitz, also designed by Morrison, had a similar if not even more impressive cross bunkering as Falkenstein’s No.3 after the redesign. Construction of the second hole was finished in 1939 and during autumn of the same year the new 3rd fairway was cut through the forest. The two holes were opened on August 30th 1941. The “Reincke-Höhe†became a very popular spot for spectators, as from that spot you could watch the golfers on green No.2, Hole No.3, Green No.6 and Tee No.7. The creation of these two holes has definitely strengthened Falkenstein with the addition of a true three shot hole and a long one shotter. Plans for work on the back nine were shelved for twenty years due to World War II.

Meister provides this photograph as to how the third hole appeared in 1941 after the playing corridor was relocated and the hole lengthened by C.A.Hellmers. A wood was sometimes required to reach the back hole locations.

Here is how the third hole now looks and plays today after von Limburger himself modified it in 1961. His alterations offer a real insight into how he approached golf course architecture. Specifically, he was a fan of fewer hazards but that they should be well placed. In that manner, the maintenance expense would be reduced while the course would be strategic and enjoyable to a wide range of playing levels.

Of course, one may wonder that if the creation of the new true three shot second hole was so beneficial to the course, why didn’t Harry Colt himself build it? The answer is simple in that the club did not own the property in 1929 and that Harry Colt‘s first hole played into the corner of the club’s property as it existed at the time. Hence, Harry Colt had no choice but to send his second hole back down what is now mostly occupied by the club’s practice area. The land two hundred yards behind the first green that the club eventually acquired in the late 1930s was in fact a sand quarry (!) and there is no doubt that Harry Colt would have found a way to incorporate it into his routing.

By the early 1960s, as Europe heeled, thoughts again turned to what was best for the course. Meister continues the story on the evolution of Falkenstein,

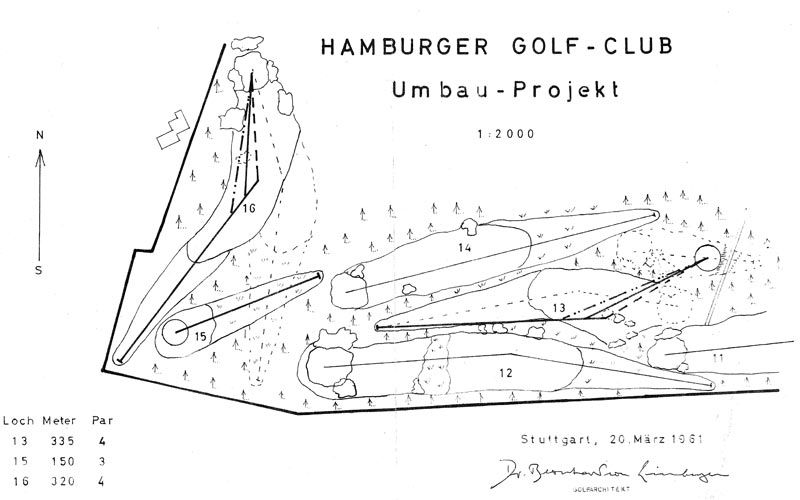

The members of Hamburger Golf Club had to wait until 1961 to pursue the pre-war idea to lengthen the course to more than 6,000m (6,562yds). Bernhard von Limburger, who in 1930 had written that No.13 was probably the easiest hole on the course, brought forward the idea to close the Par-3 14th and lengthen No.13 by 40m by putting the green onto the edge of a ravine that was formerly part of hole No.14. Ever since then, No.13 has been a challenging dog-leg Par-4 hole. It might make the reader smile to hear it was von Limburger himself who said during this time at Falkenstein that he felt like a painter who was sent to the Louvre and being asked to prettify Mona Lisa’s mouth. Old No.15 became no.14 and the hole was lengthened by a few meters putting the tee where there was formerly green no.14. Now the course needed a second Par-3 hole on the second nine and so the spectacular downhill par 3-hole was added between old No.15 and No.16. As Mark Rowlinson states in the latest edition of the World Atlas of Golf, “the 155-yard 15th is almost as far down as it is long! It seems quite out of character with the rest, as does the 329-yard 16th, a short par four that involves a drive which must pierce the narrow gap between two tall trees. Neither is a Harry Colt originalâ€. Right he is as both holes are the work of von Limburger and not Harry Colt or Morrison. The new No.15 necessitated moving the tee of No.16 westwards to the outset edge of the golf course. No. 16 now became a dogleg and just recently German-Canadian architect David Krause added a nice deep bunker where long drives will end up if they don’t get around the corner of the dogleg. The second part of the hole as well as the position of the green is original though. Some people say 15 and 16 are the weakest holes on the course, all I can say is that on most German golf courses they would be considered nice holes. The end result is that after the 1962 and 1965 renovations Falkenstein played 6,010m (6,573yds). The course was again well suited for Championships such as the German Open, which was played at Falkenstein eight times between 1951 and 1981 when Bernhard Langer won the tournament for the first time.

The changes to the 2nd, 3rd, and 13th-16th holes are evident above when the 1970 course is transposed over Colt’s 1930 routing.

In looking at the routing above, the upper middle section where it shows the second green, third tee, sixth green and seventh tee is the Reincke-Höhe, the highest point on the course. How devastating it would have been if the club founders had been insistent that the clubhouse be located here! Mercifully, they didn’t handcuff Harry Colt in this manner and he was free to incorporate that landform into the golf. Far too modern day owners/founders of courses make the mistake of allocating prime land for golf for the clubhouse instead. This blunder helps doom many a modern course to mediocrity.

Hole to Note

Fourth and Fifth holes, 480 yards & 430 yards; As referenced above, Falkenstein gets off to a solid start that requires stout hitting but the course becomes altogether more special starting on the fourth tee, thanks to Harry Colt‘s innate ability to route holes over landforms in such a manner as to create unique, arresting holes that live long in the player’s mind. The manner in which the fourth and fifth fairways are draped over the rolling land is Harry Colt at his very best. At both, the holes dogleg to the right over crests of hills with out of bounds on the inside of the doglegs and guess what? That leaves blind tee shots of the sort that the modern tiger golfer despises. Yet, standing on the tee, all but the first time golfer (of which there aren’t too many at this private club) knows exactly when he has executed a good drive. The reward of a long tee ball that is properly shaped from left to right is that the golfer enjoys a much easier second shot after his tee ball receives additional kick and roll off the sloping landforms. In the case of the fourth, this half par hole becomes reachable in two. Though the visuals are perfect on holes two and three, it is when more mystery is presented that Falkenstein becomes truly special.

Colt used the broad slopes and ridges to great effect, especially on the front nine. Both the tee balls on the fourth (see above) and fifth are blind and play over the crest of hills.

Sixth hole, 430 yards; In the first several months from when the course opened, hickory shafts were the norm but that quickly changed. Always keen to test the best, Falkenstein looked where it could best pick up length. At the sixth, they were able to both move the tee back fifty-five yards and also shorten the green to tee walk from the prior hole. The only downside was that the new tee made the hole more of a pronounced dogleg right than Harry Colt initially had it, meaning it was the third hole in a row that is shaped from left to right. Nonetheless, the hole is a standout and plays completely different than the prior two due to its uphill nature. If anyone was ever inclined to compile an eclectic list of Harry Colt‘s hardest holes, this would be included! The Nordwand of the Eiger is often referred to as the Wall of Death and that’s how someone in a stroke play event might view this brute.

A monster of a two shotter, the sixth hole climbs eighty feet from tee to green. As if that’s not enough, its green features the most back to front slope of any on the course.

Rare is it for a hole to climb so dramatically on both the tee ball and approach shot. As seen above, the contoured green offers no respite.

Seventh hole, 380 yards; As noted above, the highest point at Falkenstein is called Reincke-Höhe and it bears the sixth green and seventh tee with the second green and third tee some thirty yards lower but cut into the same landform. Variety is at the heart of all great architecture and that is exactly the opportunity that topography affords the architect. What could be more different than the bruising sixth with its uphill climb and fiercely sloping back to front green? The answer is a downhill hole with a green that falls away to its back right which is exactly what Harry Colt built. Such diversity is extremely rare to find on a flat course.

Hamburger is hillier than most heathland courses around London. The prospect from the elevated seventh tee is friendlier than the prior three tees as everything is clearly laid out before the golfer. A drive down the left best opens up the green.

continued > > >

Hamburger Golf Club

Hamburg, Germany

Eighth hole, 180 yards; When taken as a set, one shot holes are typically among the strengths of any Colt design as he famously searched out ideal green locations for them early in the routing process. Here is different though as Colt didn’t design either the third or fifteenth holes as they play today. Thus the golfer is left to appreciate only two Colt one shotters, being here and the tenth. This is the most attractive of the bunch and it serves as a transition hole. As previously noted, the land at Falkenstein was largely open and Colt didn’t have to fell near as many trees as on some of his other inland projects. However, with this hole, Colt takes the golfer from the open heathland and points him toward the most densely forested portion of the property. The next four holes are more tree lined than what has gone before.

Though just a one shotter, the eighth is a transition hole. The tee area is in a sea of heather while the green is nestled into the trees. The next three holes are more akin in playing in a forest before returning to the more open part of the property as seen at the twelfth below.

Twelfth hole, 390 yards; One of the best holes in Europe, Colt perfectly incorporated the hill’s shoulder into the playing of the hole. However the golfer elects to do it (a chasing draw that takes the slope and runs to the left or a drive long down the left), the golfer wants to find the left half of the twelfth fairway from the tee. From there, he will enjoy something close to a level lie to a built-up green that is heavily defended short, left and beyond. How the right side of the green ties in seamlessly with the hill is first class and give J.S.F. Morrison credit as he supervised the construction of the course for the firm of Colt, Alison & Morrison.

Thirteenth hole, 340 yards; At least to this writer, this is the best of the non-Colt holes as it captures some of the playing charm that Colt imbued into his work. A central bunker is located right where a well hit three wood would like to finish. Does the golfer dare risk hitting over it with a driver into a narrow neck of fairway? Perhaps but why take a risk only to be left with a dreaded half wedge/feel shot? Time has convinced many members that it is more prudent to lay back from the tee, be sure to hit the fairway, and then come into the sharply tilted green with a full short iron.

Colt’s original hole played straightaway and slightly to the right of the central hazard seen above. His next hole was a par three to an area near today’s green. Give von Limburger credit for successfully combining the two holes into a fine, testing short par four.

Bernhard von Limburger’s drawing shows how he combined a short par four and a short par three by Colt into today’s thirteenth. This copyrighted drawing is used with the kind permission of the Deutsches Golf Archive in Cologne.

Seventeenth hole, 480 yards; In contemplating Falkenstein and where it fits relative to Colt’s best work, it has two great attributes in its favor. First, it enjoys lush and healthy heather that lends the course much texture and flavor. Second, in the hands of a master architect, its rolling topography meant that a number of distinctive holes would emerge from a successful routing. No architect has ever been better at routing eighteen holes than Colt and this is a prime example. To that end, both the seventeenth and eighteenth holes utilize the heather and topography as well as any on the course. As a result, the course gallops home in an invigorating manner. If only the Dunluce Course at Royal Portrush could have finished with two such sterling holes, then there would be no debate as to Colt’s finest work.

Two blind drives over large swaths of heather finish off the round. Does any Colt course finish with two finer holes? Perhaps not.

Colt cleverly used the heather as central hazards at Falkenstein. A good drive that carries the crest of the hill gets a big kick forward and leaves this enticing approach shot from appoximately 200 yards into the green, making this a world class half par hole.

Eighteenth hole, 380 yards; Rare is the Colt course that plays favorites to a certain shape shot. Generally, Colt made sure that his holes hit the land in differing ways with the end result being the golfer was called upon to hit different shape/type shots. This holds true at Falkenstein as well though, truth be told, each nine does favor a particular shot. The first nine with the fourth, fifth, sixth and ninth bending to the right certainly is well suited for a fader of the ball while the second nine with the thirteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth going right to left fits the eye perfectly for the drawer of the ball. Over the course of a round on a Colt course, the player who can hit shape his ball at will enjoys an advantage, as it should be. Though the golfer is not necessarily rewarded visually with a well constructed shot (i.e. a fade at the fifth or a draw here at the eighteenth) because his tee ball disappears over a hillcrest, he is rewarded with a much simpler/shorter approach shot based on how his tee ball interacts with the ground. Good players relish the subtle playing qualities of a Colt course as Colt allows them to show off their full arsenal of shots.

Colt benched the eighteenth tees into the hillside behind the seventeenth green, creating one final attractive blind carry over the crest of a far hill.

Assuming all has gone well with the drive, the golfer finishes with a short iron approach to an interesting green. Why can’t more courses finish in such style?

The tenor of the course briefly changes at the fifteenth and sixteenth. The first is a short drop shot par three of the sort not found on a Colt course and the next hole is a short par four that plays between two large hardwoods that dominate the landing area from the tee. Neither enjoys the playing qualities of a Golden Age course and thus they don’t feel quite a home on a Colt course. Indeed, the club owned the land that the fifteenth green and sixteenth tee now occupies and the fact that Colt and his partner Morrison opted not to utilize that corner of the property is telling. Nonetheless, the manner in which the course steams home with the last two holes leaves the golfer highly desirous to keep playing.

Travelers who take the time to know Hamburg are left wondering if this diverse port city isn’t among the two or three finest cities in Europe. Similarly, those who take the time to get to know Falkenstein can’t help but fall under its considerable charms as well. Though five of the holes aren’t original to Colt, they add to the overall mix of shots that are required in the modern game. As it stands, Falkenstein joins a select few inland courses (De Pan, Morfontaine, and Saint-Germain) on contintental Europe that are a must see for devotees of classical architecture.

As seen from behind the second green, Falkenstein’s rich texture and hills leave a distinct – and deeply satisfying – impression.

The End