Glens Falls Country Club

New York, United States of America

Nestled between the Adirondacks and Green Mountains, Glens Falls seduces rather than overwhelms and is one of Donald Ross’s most engaging designs.

Typically, the more events a club hosts (especially if professional players are involved), the worse a golf course becomes. This sad but accurate observation is largely unique to golf. Most other sports arenas receive enhancements in order to stage prestige events but for championship golf countless Golden Age courses have been altered/mutilated for the sake of difficulty in order to ‘test the best.’ Some clubs (Augusta National, Carnoustie, Pebble Beach) do an excellent job of hosting events but eventually fall prey to poor judgement. After debacles like the U.S. Open at Shinnecock Hills in 2004, it’s a wonder that grand clubs still even agree to host such events!

On the other hand the lack of television may mean that fame will be slow to arrive. Such is the case with Glens Falls, located north of Saratoga Springs in upstate New York. Tom Doak in Volume 3 of The Confidential Guide asks, ‘How has such a fine course escaped attention this long?’ True but what a delight to discover it! Canadian golf architect Ian Andrew has been the architect of record since 2011 and recounts his initial visit:

The first time I came here, I was immediately awestruck by the undulations on the opening hole and was eventually grinning when I passed the seventeenth green. It turned out that I hadn’t seen anything yet and as we worked our way around I was blown away by its brilliance. I appreciated how Ross incorporated the diagonal ridges into landings, swales in front of green sites, occasionally bizarre and always brilliant interior green features, tee balls that played “up” to the mid-ridge brow, epic shots into the valley, greens set on the edge of an abyss, natural plateau green sites and most of all the holes that slide away from the golfer playing down the mid-ridge. Ross made many outstanding decisions and then backed them up with even better architecture.

At Glens Falls one can often look back from the green (in this case, the tenth) and find that the hole’s high point is between you and a tee hidden by the fairway contours. Judging how and where to land one’s ball and have it trickle onto the green is part of the charm of a game here.

Andrew goes on to say, ‘The course was an architectural education. I went out to play after finishing a walking tour and 18 holes were not enough and began to replay “on the run” as many holes as I could till I found myself on the eleventh as the sun set. Only the thought that wolves might exist caused me to retreat!’

Ross’s first nine holes opened in the 1910s and all eighteen were in play by the early 1920s. Today’s course is largely as Ross left it. The exceptions are related to the fairway lines altered by tree growth and a bustling country road that caused an alteration to the sixteenth. Thankfully, no insipid ponds or water features have been added like those that mar the East Course at Oak Hill or Congressional. Instead, trees were allowed to proliferate but the club has started to gain the upper hand recently. For example, take the valley that the second hole occupies and that the mighty twelfth brushes alongside. Just five years ago, six fifty foot tall evergreens lined the far valley wall, shielding from view the upsweep to the twelfth green and beyond as one stood on the second tee. Shrouded in shade much of the day, the second fairway was perpetually damp and soft. A sense of its rollicking topography was muted and its fairway width compromised. As for the twelfth, the steep drop off to the right wasn’t as keenly felt standing on the tee. In both situations, the natural attributes were inadvertently snuffed out instead of highlighted. When the trees were removed in 2011, both holes could ‘breathe’ again and their singular attributes amplified.

Aptly named after its glorious location, Glens Falls offers important advantages similar to those at Pebble Beach or the Homestead where vacationers have been drawn to its beauty for decades. Additionally, America’s early history played out across this region. Whether your interest lies in George Washington’s exploits or the native American Iroquois, there is plenty to do. J. Lewis Brown, the former editor of Golf Illustrated, authored Golf at Glens Falls in 1923, states it well:

‘And what an ideal setting the course has! Not content with providing all the historical associations which make it of great interest to tourists and others, Nature has outdone herself in her own way. Picture with me if you can, range after range of mountains which rise up to meet the blue sky, their blue and purple peaks blending with the azure blue of the fleece-flecked heavens and their verdantly laden slopes, with their lofty pines and evergreens, forming an almost artificial fringe for the course itself. Donald Ross’ {sic} creation lies in the valley of this huge ampitheatre and even if such a master has not played such a prominent part in the construction of the course, the natural beauty of the place would have endeared it to every golfer.’

Like so many great courses golf clubs are not a prerequisite to enjoy being on this property! To the surprise of no one, Ross’s routing capitalized on the natural features and a series of arresting holes followed. Andrew’s advice to date has been straightforward: ‘Get the course to play the way it should first. Then we will look at other details to improve. So for the last few years we have concentrated on proper grassing lines, often outside the bunkers, to restore options and reintroduce alternate playing routes.’

Glens Falls packs quite the punch considering that it measures less than 6,500 yards. It’s praiseworthy that the club has seen fit to keep it that distance. Still, the author had the opportunity to play with member Anders Mattson, Director of Instruction at Saratoga National Golf Club, whose textbook swing generates disturbing power with little apparent effort. In fact, he drove over the par 4 seventh green with my hickory driver! Mattson notes ‘Unlike any other place I’ve been, this golf course makes me want to play golf. It may not be considered long any more but I have never seen anyone overpower the course. For instance, I might get near or on the par 5 fourth green in two but that green has a way of turning two shots into three.’

The swale in front of the fourth green eventually leads to a back right knob as well as a lower left bowl that houses today’s accessible hole location. Greens like this with its soft shoulders and interior contours keep the best at bay.

Mattson’s words echo those of Mr. Brown opining in Golf at Glen Falls: ‘it is a course that grows on you. The more you play the more you want to, and every time you do you’ll find some new wrinkle that Donald Ross and nature have put in just to take care of that particular erring shot of yours. I’m going back to play it again. I am going to have my revenge. Can you – as Baucis inquired of Philemon – beat it?’

For the author it’s this form of golf – man alone with nature’s splendor – that should be celebrated and trumpeted far more than that generic thing called ‘championship golf.’ The freshness of the course and the exhilaration of being begins at the first tee, which is located below the clubhouse and reached by traversing a quaint wooden bridge. It concludes in a fittingly unique manner with a par 3 adjacent to the clubhouse and there is nothing not to like in between, as we see below.

Holes to Note

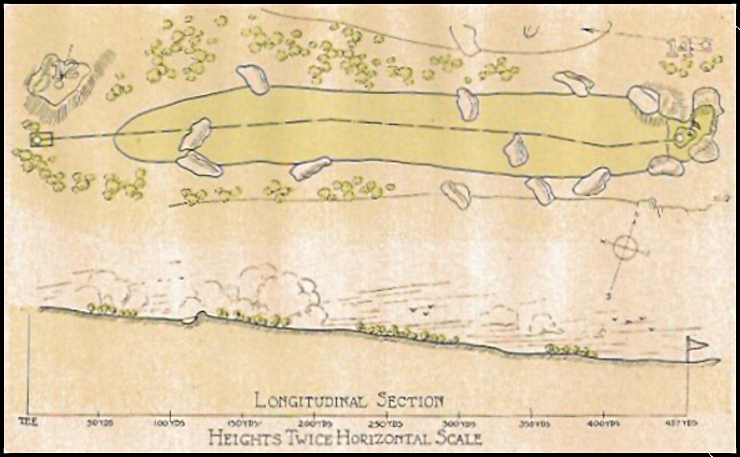

Second hole, 400 yards; No architect in history has built more holes that play from an elevated tee past a fairway below to a well-draining green above. No one. Here’s a prototypical example with an attractive tee shot into a valley. As usual, Ross places greater demands on the approach resulting in one of the hardest shots confronted all round. Having said that, where Glens Falls distinguishes itself among Ross’s courses is that this is the only such hole on the course! (The eighth and seventeenth are possible exceptions, depending on how far one elects to advance his tee ball). The great preponderance of holes ask the golfer to hit down to greens.

Third hole, 170 yards; Played into a corner of the club’s property, this one shotter features a wickedly canted back right to front left green. A ball might release and meander as great a distance across this putting surface as on any other green on the course. It’s a shrewd ploy by the architect: show the golfer your most evil greens early in the round to make him wary the rest of the way. It’s pointless for an architect to hold his best stuff until late in the round as he will have squandered a psychological advantage that he could have gained in his chess match with the player.

Fifth hole, 340 yards; Situated on the least interesting part of the property, Ross compensated by building one of his all-time great putting surfaces. Many modern architects would move prodigious volumes of earth tee to green in a desperate effort to enliven a calm portion of the property. Ross knew better. What really matters is the quality of the ultimate target: the green.

As seen from back right, this unique contour has earned the fifth green the moniker of a ‘top hat’ green.

Sixth hole, 400 yards; Half of the fourteen non-one shotters (e.g. the fourth hole, here, ten, eleven, thirteen, fourteen, and fifteen) play up and over the crest of the hill that dominates the middle of the property. This is likely the best of the bunch because of its one-of-a-kind roly-poly putting surface that is much broader than deep. The first time visitor may well have never seen anything like it, which speaks volumes as to the originality of this Ross design.

Note the graceful swales and rises that define the sixth green complex. Typically such rounded contours are only found on sand based sites. Today’s right hole location in a semi – punchbowl elevates the hole from being hard to being both hard and fun.

Seventh hole, 290 yards; Brown (did he love golf or words more?!) quotes Drayton as saying that ‘Sirens sing sweetest when they would betray.’ As well a designed hole as you will ever find, three bunkers are artfully cut on a diagonal into the far slope of the valley wall. How and where each player wishes to place his tee ball is ability dependent but ideally one long and right leaves the golfer but a pitch to an open green on the same level. A slight pull or overcooked draw from the tee shifts the advantage to the architect as the pitch is played from either a hazard or from well below the surface of the green.

The drivable seventh scores a 10 out of 10 for design and deserves to be celebrated with Ross’s finest short two shotters.

Eighth hole, 360 yards; Alister MacKenzie once lamented that no one said anything bad about Cypress Point. He feared that meant that the architecture was too tame! Clubs that routinely host events invariably have their controversial features snuffed out. The most polarizing single feature at Glens Falls is the ski-slope pitched putting surface at the eighth. Great care must be taken when selecting the day’s hole location as things readily go haywire if the hole is cut on too much of a slope. Truth be told, that leaves only a few spots. Andrew’s advice to the club is to hold strong for now: ‘The eighth green is a conundrum for the club. It’s clearly too steep, but also one of the most memorable greens sites because of it. When asked if they should consider rebuilding it, I answered that every great course has one green that seemingly crosses the line, but if there’s a way to play for an unconventional par, then it should remain. Yes, the eighth green is really hard, but it has not crossed that threshold.’

Ninth hole, 150 yards; As noted in other Ross profiles on this web site, Ross had a penchant for building ‘Volcano’ green complexes for short one shotters. This is one of his best, though the player who misses left or right and finds himself some thirteen feet below the putting surface is unlikely to agree. That there are no longer bunkers at the base of the green complex adds to the dilemma because the golfer is as likely to draw a squirrely lie on hard clay as one sitting up nicely on grass. Witnessing play within your group at this modest length hole is always entertaining as the golfer’s greed is pitted against the need for prudence. Which force wins out is starkly visible to all!

Playing this hole is not unlike the seventeenth at TPC Sawgrass: ignore the hole location and just aim for the middle of the green.

Eleventh hole, 435 yards; Given that the hole’s high point is in its middle, pressure is placed on the golfer to get away a good tee ball, least he suffer a lengthy, blind second. Similar in key respects to the sixth, this longer version – mercifully – features more beneficial ground game options on the approach. It’s worth repeating: a plethora of downhill approach shots provides the course an uncommon abundance of ground game interest for a course so far removed from the sea. As such the course surely ranks high on Ross’s own list of places where you would like to learn the game as well as grow old. Add in the world-class holes sixth, seventh, ninth, eleventh, twelfth and seventeenth holes and behold a course you want to play your entire adult life as well!

Playing a carom approach shot off the hillside would be fun for all skill sets, so the author hopes that this fairway can be expanded to better accommodate such.

Twelfth hole, 225 yards; What a thriller! On par with the breathtaking thirteenth at The Addington, the golfer delights in the task at hand despite the obvious difficulty. Brilliantly routed parallel and just below the dominant ridge line, quite a bit of dirt was required to bench the tee and enormous green pad against the hillside. It’s a testament to Ross and his crew how peacefully the hole rests upon the landscape. Similar to another famous twelve hole found in Georgia this one can be a card wrecker. It also anchors Glens Falls’s own three hole version of Amen Corner, where even the most talented struggle to keep up with Old Man Par.

As seen from the 190 yard tee markers, note how Ross artfully benched the green into the hillside. The removal of evergreens along the right hillside has allowed the hole to regain its epic quality.

This view from behind better captures how uphill the tee ball actually plays. A back middle puff in the green helps feed balls toward right hole locations.

Thirteenth hole, 455 yards; Another up and over hole capped off by the kind of approach the old trooper aches to play. Scooting an approach past the multiple hazards and watching the little white ball trundle all the way onto the putting green is sheer delight. From well back in the fairway, the golfer is afforded the ideal vantage to watch such a shot slowly unfold which surely beats the modern version of hoisting an aerial shot high and seeing the ball dully splat onto the green.

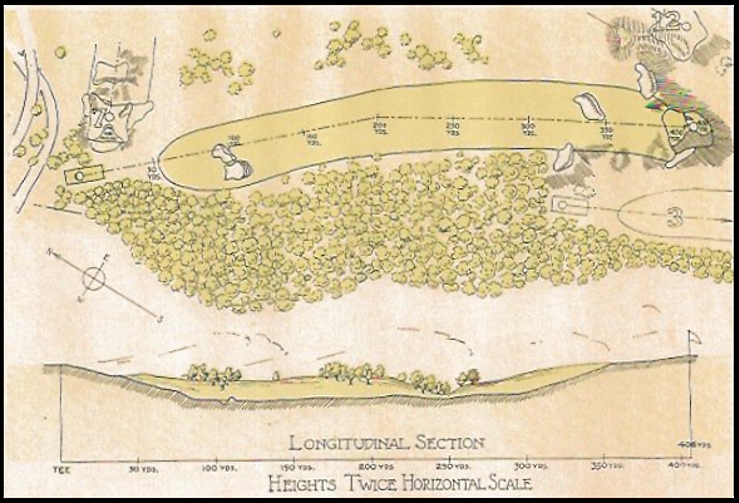

Lewis’s diagram above highlights the need to carry over the ring of hazards and then have one’s ball feed down the slope onto the open green.

The land and green follow the slope of the land, which is to say that they fall away from the player.

Fourteenth hole, 370 yards; Golf historian David Normoyle, who lives in Saratoga Springs, some thirty minutes away, is a former member and has as keen an eye for architecture as anyone. He knows the course well and deems this hole his favorite: ‘Glens Falls is an attractive course because it has so many natural holes with thrilling topography. But my favorite hole is the fourteenth, primarily because it has more clever Ross architecture than any hole on the course. Relatively short, dead straight and only slightly uphill, the land is unimpressive. Classic hazards challenge off the tee, with bunkers staggered left and right. Taking on the more imposing left bunker sets up the preferred angle to a broad, subtly undulating green with a skyline backdrop. Open at the front, the green presents a simple target to hit but a challenge to get close due in part to the intimidating natural falloff behind. Ongoing green expansions have recaptured the most tempting corner hole locations and reconnected the deep greenside bunkers. As for the skyline, until recently there was no skyline feature only a dense wall of ill-considered trees that stripped the hole of its primary charm. Though there are still more trees to be removed along the playing corridor, this cunning hole makes the player think on every shot and is deeply satisfying to play in a way that suits one’s abilities and appetite. You could probably play it with a putter, if so inclined, but to score requires bold, thoughtful play. And, that endless backdrop is just awesome.’

Given the steep fall off behind, chasing after back hole locations is one of the day’s tenser moments. The trees in the background are 300 yards away; in 2010, a row of trees formed a backdrop just 10 yards behind! As the trees and mow lines improve, Glens Falls rise in fame has followed.

Seventeenth hole, 400 yards; Though the author lives in the Southern Pines/Pinehurst area, even he acknowledges the overwhelmingly superior advantage and allure of the Northeast’s tumbling topography. The view from the tee here is one of those WOW moments that happens rarely in the Sand Hills of North Carolina. Brown leaves no doubt as to its merits: ‘There is no mistaking that this is by far the best two-shotter on the course and one of the best I have ever seen.’

The view afforded the golfer as he turns onto the club’s entrance road (seen above the green) informs the golfer that a special day lies ahead.

Restraint from the tee leaves the golfer with a relatively level stance for his approach to a green at the same height. Beware the false front.

Eighteenth hole, 150 yards; A course this charming deserves to end poetically. Essex County does, Mid Pines does and happily, the lyrical Home hole does so for Glens Falls. The tee frightfully close to the clubhouse patio points to an angled green that features a distinct rise. Under the watchful eyes of the discriminating membership a shot that finds the proper plateau for the day’s hole location is tantamount to glory. Alternatively, an unfortunate mis-hit into the water can be mitigated by an immediate retreat to the bar (140 yards nearer than the green).

So concludes the round, beneath the clubhouse and by the same enchanting lake upon which the round commenced. What a walk it is too! Some quibble about the 150 yard plus green-to-tee walks from fifteen to sixteen and again to seventeen. So be it. Their origin stems from when Ross’s straightaway 400 yard sixteenth was converted to a dogleg left par 5 due to increased automobile traffic on the country road that Ross’s hole crossed. The author likes the addition of a par 5 to the second nine, as well as the fact that it swings in the opposite direction to the par 5 first. Rather, the author’s prime concern is that the club stay on its present course of removing interior trees that block the views of the surrounding mountains. This romantically located valley course merits a keen sense of place, something that tall evergreens do little to encourage. Let Ross’s hazards dictate play, not decades of tree growth.

Happily, continued tree work remains a focal point. Andrew explains, ‘In 2015 Golf Superintendent Chris Freilinghaus and I marked out the last of the grassing line adjustments. Some were done this fall and the rest will be done next year. During that walk, we began to talk about future tree removal with the Greens Committee. We discussed opening up more views across the course, removing the conifers that have imposed themselves into play and returning the original scale of the design.’ This is good news indeed!

As seen from the high point of the course (the thirteenth tee), no reason for the evergreens to shield views of the Vermont mountains.

Andrew’s voice of reason is a perfect match with the club’s reticence to preserve what is already very good. Andrew notes, ‘The membership has the ideal mindset for this course. They are not in a rush to do anything. We meet to consider things and often let them sit for a year or two before talking them through one more time.’ If only more Golden Age courses had such good stewards! A club’s board is meant to look after the best interests of the club member. Happily, that continues to occur here and hopefully the fame that this course is now finding won’t alter that one iota.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)