Friar’s Head

NY, USA

Green Keeper:Bill Jones

The natural hazards at Friar’s Head are unique to the site and thus, the course reminds one of no other in the world. Pictured is the one shot 10th.

Howman interacts with nature is at the heart of golf course architecture.

Max Behr spoke of courses ‘uncontaminated by the hand of man’ and of natural courses that possess ‘a certain charm wholly lacking upon a palpable man-made golf course.’ C.B. Macdonald wrote in Scotland’s Gift that ‘When playing, you want to be alone with Nature. Glaring artificiality of any kind detracts from the fascination of the game.’ Later in the 1920s, hewrotewith regard to National Golf LInks of America that ‘the only thing that I do now is to endeavor to make the hazards as natural as possible.’

Thoughtheir wordscontain timeless truths, their message was lostduring the lastseveral decades of the 20th century.With bothequipment and money plentiful, courses became more and more landscaped. Man’s hand upon the property became heavyto the point where it wastooevident.

During the late 1980s and 1990s,there were afew architectsbucking the trend. Rather than over-stylizinga site, they were intent on following nature’slead and incorporating nature’s subtleties into their designs. The architect firm of Coore & Crenshaw was one such firm and as a result,time has proven them to be particularly successful in building courses that are reflective of their surrounds.

Of course, crucial to an architect that wishes to make the most ofthe land is a good piece of property.The opportunity to build a course from scratch in the desert replete with waterfalls, rolling hills, and imported mature evergreens is of minimal interest as they realize any suchattempt to replicate nature will yield a product that is adistant second to the real thing. Far preferable is a varied piece of property full of natural hazards. As Coore remembers thinking when he first got in the industry in the early 1970s, ‘in this business, you can’t ask for any more than a decent piece of property with some naturalfeatures and a principal who allows us to work.’

In theearly springof 1997, just such an opportunity presented itself when Ken Bakst invited Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw to tour a 350 acre block of land outside of Riverhead onLong Island. In hindsight, it would prove to beCoore & Crenshaw’smost exciting piece of property since Sand Hills.

Initially, Bakst drove Coore and Crenshawonto the propertyvia an oldservice road. The first bit was through trees butthen they came to aclearing, alandscape with wide expanses of 60 foot sand dunes dotted with natural vegetation. Yes, indeed, this property mightwell be different from most(!), thought Coore.

Coore instinctively knew this enticing, rugged look would serve as a guide for the rest of the course.

The three men tromped around 125 acres ofmassive wooded rolling dunes for most of the day. To thenorth, the dunes gave way to150 to 200foot bluffsoverlookingLong Island Sound.To the south was farmland, which uponcloser study,possessed natural depressions and featureson a human scale. Coore & Crenshaw were sure holes of interest could be found and/or createdon the farmland portion of the property; the challenge was to find naturalholes with golf quality in the dunes without doingany major alterations and to have those holes link to the onesin the field.

For the rest of 1997, and with no signed contract, Coore made several sitevisits to study the complex dunes portion of the property. The 15th hole wasan easy findwith a tee high on a duneand its fairwaytumbling througha natural valley toward Long Island Sound. Coore could also see the short one shot 17th hole and eventually came to see the 18th hole as well. However, Coore & Crenshawresist signingany contract until theyfindaroutingthat is pleasing to all parties and in this regard,finding a satisfactory way to get from the 15th green to the 17th teeremained a missing piece to the puzzle.

Coore kept walking through the sand dunesuntil late thatfall. On the one hand, the scale and size of the dunes was so severe as to make one wonder if there was a good golf hole in there. On the other hand,the dunes were toobeautifulto want to ‘fix’them for golf. As winter set in, Coore didn’t have an answerand he returned home.

InMarch 1998, Coore returned to the siteandhis break came when he stumbled upon the shoulder of a sand dune that was completely masked under years of organic matter and debris. He thoughtit would make for a handsome feature within a hole and workingoff it, he soon found an ideal spot for the 16th tee going 230 yards back from this dune shoulder as well as for the green complex some 150 yards ahead of it. Withthe 16th foundand an appealing routing now in place, Coore & Crenshaw signed the contract in August,1998,more thansixteen months after they first walked the property.

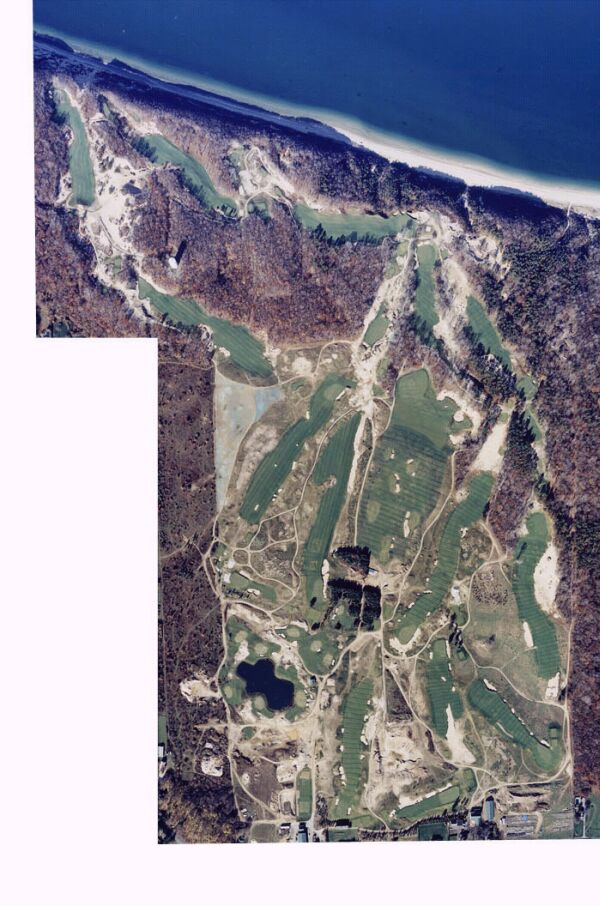

A missing piece of the routing puzzle was in finding the 16th hole. The 15th was a natural running toward the sound in the top left corner of the photograph above but finding the 16th hole and giving it good golfing qualities was crucial. The untouched 30 acres of massive dunes that is encircled by holes 10, 14-18 would have required major alterations for golf, something that Coore & Crenshaw were unwilling to undertake.

When permits were received in February, 2000, Coore & Crenshaw’s team was busyfinishing the Chechessee Creek Club in South Carolinaand the Austin Golf Club in Texas. Fortunately, Coore’s long time friend and work colleague Rod Whitman was immediately available to assist at Friar’s Head. (please note: Whitmanhas built first rate courses onhis own as has Dave Axland who ranthe Friar’s Headproject for Coore & Crenshaw).

With the general routing known, the challenge was now tying in the dramatic contrast between the dunes and the field, especiallygiven thatthe tree line abruptly stopped at the base of the dunes. As Coore puts it, they needed ‘to balancethe visuals without overpowering the substance of the golf.’ The team started on the initial clearing in February and didn’t finish for five months. Great care was taken in creating wide corridors to transition the golfer from dunes to field and vice versa.

Once shrouded in trees and covered by organic debris, Coore & Crenshaw eventually uncovered this stunning dunescape at the 14th.

Not until the clearing was completed was any dirt moved, and by this time it was July, 2000. With the exception of James Duncan who was overseeing the construction of the delightful Hidden Creek Golf Club in New Jersey, Coore & Crenshaw’sentireteamwould at one time or another work on Friar’s Headover the next2 1/2 years.What transpired during that timewas an evolutionary process, with talented professionals slowly uncovering the site’s finest natural attributes and incorporating them into a golf course.

Examples of the evolutionary process areseen in the Holes to Note section below.

Holes to Note

(Note: all yardages are estimates on the part of the author as the score card contains noyardage information).

1st hole, 380 yards; The course commences in the dunes portion of the property and from the start, Coore wanted the 1st fairway to be where it is today asitoccupies the only flat part within the dunes and he wanted the golfer to get into his game before going up and down in the dunes. Originally, the green was staked at the base ofthe hillupon whichtoday’s green sits atopwith the hole beinga short opener in the 330 yard range.However, nagging doubts persisted as after putting out, the golfer would have to climb 35-40 feet to get to the 2nd tee. Instead of benching the green 10 feet up the hill, perhaps they could do 15 or 20 feet? Finally,the suggestionthat perhaps the green should go atop the hill was thrown out.Would the uphillshotbe too much forthe first approach shot of the day?Coore asked Bakstthat very questionand thereply was an unhesitating ‘no’. Thus the trees were cleared atop the hill (though the rest of the hole had been cleared weeks prior),and so sits today’s green. As Coore says, ‘this is a prime example of letting the process evolve in the field and of avoiding a regrettable situation.’

Instead of being at the base, the 1st green now rests atop the hill.

Overemphasizing the variety of the green sizes and shapes at Friar’s Head is tough to do as the greens range from 3,300 to 18,000 sq. ft. in size and from a rectangular shaped green like the 1st pictured above to the vague boomerang shape one at the 5th.

2nd hole, 580 yards; The first transition hole, as the golfer starts high on a dune and endsat a green that was once in the middle of a potato farm. The all important question was how to gracefully transition the golfer from one extreme to the other.Coore & Crenshaw felt that these transitions were the single mostcrucial design aspect to the course’s overall success. After speaking with Coore, Whitmanwent to work in hisD-6 and shaped thedirtintorandom movements which start out bigger and more pronounced at the base of the sand dune and then gradually taper outat the green complex.Where man’s hand starts and nature ends is undetectable, the true sign of a job well done.

What a view! The golfer has no regrets that he is leaving the dunes for the next five holes.

Though half the 2nd hole is in the dunes and half the hole is in the field, the golfer is unaware when the transition occurs. Note too how the hazards are actually in play and dictate strategy, as opposed to being pointlessly to the sides of the hole.

3rd hole, 480 yards; With every other two and three shotter on the course containingplentyof movement from tee to green, Coore & Crenshaw let thisfairway stand as they found it, which is to say essentially flat.In that manner, the hole is reflective of its surroundswhile at the same timestretching the variety ofthe course. Of course, there are subtletiesin theapproach with a slight rise at the front left corner of the green nudgingballs into the awaiting left greenside bunker. On a recent visit, the mowing lines were being adjusted to ensure that only short grass was between the green and that leftbunker.

Coore & Crenshaw made the barn behind the green a dominant feature of the hole. The sites of Friar’s Head and Royal St.George’s in England share the common attribute of having both wild dunes and flat portions as well. As is the case at Royal St. George’s, several of the hardest holes at Friar’s Head are on the flatter portion of the property, including the tough two shot 3rd.

4th hole, 230 yards; This long one shotter is at a right angle to the 3rd hole. To break any hint of monotony that can come in a flat field, Coore & Crenshaw placed a series of diagonal bunkers across the tee and ranthem 160yards to theleft of the green. Thus, the tendency off the tee is to steer the ball a bit to the right, away fromthis obvioushazard. The problem arises as the green slopes from right to left, making a recovery from the right problematical.

No extraneous earth moving clutters the picture of the 4th.

A game at Friar’s Head is about options and creativity: does the golfer want to bounce it onto the 4th green? Play a cut? A draw? Fly it on? Coore & Crenshaw don’t force the golfer to play any one particular shot.

5th hole, 330 yards; Pete Dye, whom Coore worked for from 1972-1975, stresses variety is the key to good design and this is the kind of frustrating/tempting two shotter that nearby Shinnecock Hills doesn’t have. The challenges off the tee shift with the wind,from being drivable downwind to avoiding three central hazards shy of the green into the wind. The multi-option 5th is proving to be one of the most confusing holes on the course to play. Should one be bold off the tee or not? Frequently, those suckered into hitting driver by the generous fairway width often times regret their decision,as their playing angle into the small green can be worse than if they had laid further back.

Which way to go off the 5th tee? The answer depends on the day’s wind and hole location.

An approach from the right to a left hole location is no bargain, thanks to one of the most confounding features on the course: a series of contours culminating in a knob just shy of the green. Though small, the knob dominates much of the hole’s play.

An approach from the left is somewhat easier for today’s hole location. The rippling ground was generally a lost sight in American golf architecture from 1950-2000 when speedy construction and heavy machinery were the norm.

6th hole, 430yards;A classic dogleg hole around and over a natural depression with an interesting twist:this one is a switch-back hole, with the architect asking the golfer to first draw his tee ball and then fade his approach. This ploy is a favorite of Pete Dye’s but unlike Mr. Dye who would likely bunker the right of the green, Coore did not. Any approach that hits the right or back edge of the green is likely to catch the closely mown bank and drift/bound anywhere from six to twenty paces away from the putting surface. Though the green complex doesn’t look as fiercely defended as many of Dye’s greens, it plays harder in fact.

From the very outset, Coore knew he would incorporate the depression pictured on the left into the routing of the course. The 6th was the first hole found on the course.

The closer one drives to the inside of the dogleg, the more level the stance and the better the angle into the green. No mounding ‘frames’ the 6th green to comfort the golfer.

7th hole, 540yards;Visually stunning from tee to green as the golfer is re-introduced into the dunes, the real marvel of the hole may be its putting surface. The general outlines of the green contours were uncovered as they cleared the site and their task was to make the abrupt land forms function for golf. Rod Whitman roughed it in and then inch by inch, Jimbo Wright started refining the land forms to that end. Eventually,Jim Craig and Dave Axland also had a hand in the design of this green as well. They continually focused on making the green work – if the golfer has the imagination, there is generally a way to get from one portion of the green to another.

The scale of Jeff Bradley’s bunker work was key to transitioning the golfer from the field back into the dunes. The diagonal angle created by the dune in the distance creates the strategic interest for the second shot.

The variety of green shapes, sizes and interior contours has critics claiming the greens at Friar’s Head to be the finest set built since the Golden Age of course design.

Though accomplished golfers may reach the 7th green in two, the stunning green as seen from its back left will make them work for their desired score.

8th hole, 170 yards; Theuphill tee ball is hard to gauge as the green is high on the dune.The diagonal ridge in the green exacerbates the challenge and in fact, the left greenside bunker isn’t a bad place to miss when the hole is on the top portion of the green.

Note the exposed sand dune behind the 8th green, which helps reinforce the fact that the golfer has returned into the dunes.

9th hole, 395 yards; Routing a hole along a dune ridge is often not possible because either there isn’t enough space to situate a fairway or because it would compromise how many other holes could utilize the dune. Happily, such was not the case here,allowing the 9th to get off to a rousing start. After crossing the tumbling topography for the first three hundred yards, a dull green would have been a genuine let down but the five foot (!) knob encased within the green makes the approach to 9th green one of the most fun shots on the course.

Coore & Crenshaw routed the first portion of the 9th fairway along the top of the dune before…

… having the fairway dogleg right and drop to the green below.

Almost a full year (!) went into the design and construction of the 9th green complex. It evolved from a potentially bunkerless green that is half today’s size into one of the course’s most striking green complexes.The knob is completely encased within the green, in contrast to the knob at the 5th which is only partially maintained as green.

10th hole, between 120 to235 yards; As Coore wanders the woods, he comes upon what he describes as a ‘giant ant hill.’ It is such a unique feature that he wants to incorporate into the design and yet, it’s so unique, that once the land is cleared and the ‘ant hill’ fully exposed, the team can’t help but wonder if itis too much, too abrupt. This same team faced similar decisions before (for instance, with the bold land form that was eventually incorporated into the 6th green at Sand Hills). Here at Friar’s Head, Coore recalls the day that Ben Crenshawal so concluded to leave it as is and with the team in agreement, another natural feature was left as they found it.In so doing, Coore & Crenshaw help re-capture some of the thrill of adventure that was present in golf’s earlier years with the links in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The less pronounced natural land forms on most inland courses yield conventional one shotters that pale in interest to a hole like this one.

Horace Hutchinson wrote that ‘Naturalness in a course also implies holes guarded by natural hazards, and more particularly by natural turns and twists in the ground designed by the hand of Providence to tease the cut-and-died approaches. We are in danger of monotony on the course which any one of these, or other, artificers plans for us, because they follow good principles too religiously.’ The giant ‘ant hill’ that fronts the 10th green is the precise kind of unique feature that nature yields that man wouldn’t dare.

As seen from behind, Bakst intends to take full of advantage of the flexibility that this whopping 18,000 square foot green provides. Played from a short tee to a hole location directly behind the mound, the hole is a mere 120 yard pitch. Played from the back markers to the back hole locations, the hole is over one hundred yards longer.

11th hole,600 yards;Though the 2nd and 11th parallel each other (the holes are separated by the all-world 30 acre practice area and the 35,000 sq. ft. (!) putting green that rivals the Himalayas at St. Andrews for fun) and head in the same general direction, it is hard to imagine two more different holes. The 2nd tee ball is out of a chute of trees whereas the 11th tee is on the edge of the dune. The golfer’s eye is drawn the full length of the 2nd whereas the 11th fairway bends left where a sand ridge bisects much of the fairway at the 320 mark.A fade is the ideal long approach to the 2nd whereas the man going for the green in two at the 11thshould hit a draw to best utilize the right to left ground slope near the green.With time, the author imagines that the collection of three shot holes at Friar’s Head will be spoken in the same manner as those at Pine Valley, Pebble Beach and Cape Breton Highlands as amongst the finest sets in the world.

Ala the 10th at National Golf Links, a hard running draw will take the right to left slope and run onto the 11th green.

12th hole,195 yards; In order to create different playing angles, Coore & Crenshaw initially built two rectangular tees side by side, which have since been combined into one tee that is35 yards in width. From the left side, a draw fits the eye perfectly and from the right, the player may opt for a straight ball, or a even a fade. As compared to the 11th green complex, the one at the 12th appears a much narrower target. In addition, it is routed in the opposite direction as the other one shotter in the field (the 4th), a definite attribute for a course in a windy locale.In fact, every one shotter at Friar’s Head heads in a different direction.

The left bunker is a fooler as it is a good eight paces shy of the 12th putting surface.

13th hole, 495 yards;A superlativehole in every respect as it is both fun and challengingfor every level player. Plus, from an architectural perspective, it is one of the most interesting holes on the course to play, though it occupies some of the least interesting property. The13th playstoward the dunes, with the backdrop preparing the player forthe final transition from the field to the dunes.This subtle transition is adesign attribute sorely missing from Spyglass Hill and other courses that suffer from split personalities.The13th’s interest was created through the use of central hazards in the 60 yard wide fairway while its enjoyment for all golfers was ensured by leaving the last fifty yardsto the green open.

The further central bunker on the left may look small withinthe generous fairway but the land forms do nothing but encourage balls to run toward it.

A bunker sixty yards shy of the green hinders a running approach from the left but the golfer who can split the two central hazards off the tee has a clear look at the green. Much attention went into making sure that the green’s backdrop was as natural and appealing as possible.

Great care was taken in exposing and incorporating (and creating where necessary) subtle land movement throughout the fairways at Friar’s Head.

14th hole, 535 yards; The last of the three shotters is also the last transition hole as the golfer remains in the dunes from here to the finish, producing an exhilarating stretch run. As with thefamously bunkered 16th at Shinnecock Hills, the golfer who can carry the hazards in a straight line from the teehas the shortestdistance to the green as well as the best look.As he bails left off the tee away from the hazard, his angles become progressively worse for his second shotand his second shot becomes blind as it must clear an exposed dune in the distance.

As with the 7th, the tiger golfer may have a crack at the green in two but the challenge becomes very exact at the green complex, thanks in part to a five foot fall from the back right to the front left of the green.

The false front sends many a ball that just creeps onto the green down into a nine foot hollow at the green’s base. Note the dramatic fall in the green from the back right to lower left.

15th hole, 460 yards; The view from the tee captures the intent behind Friar’s Head in two critical ways. First, if anything, man has done nothing but expose andenhance the natural beauty of the site. And second, the fact that this is one of thefew really good views of Long Island Sound during his round tells the golfer that Coore & Crenshaw were after the best golf holes first and foremost. Undoubtedly, other architects would have routed several more holes in the dunes. To do so,such architectswould likely havepillaged the land as they bulldozed it into a more ‘workable’ form. Not so with Coore & Crenshaw and the show of restraint brings to mind MacKenzie’s effort at Cypress Point Club. If the quality of the golf wasn’t placed first, Cypress Point would have lost much of its appeal years ago.

The thrill that comes from standing on the 15th tee is inescapable.

16th hole, 385 yards; The green dictates the play of the hole as it isthe second smallest on the course (thesmallest is the 17th) and it features apronounced back to front slope. The exacting nature of the approach provides the incentive to have a go from the tee to hit past or even carry the shoulder of the sand dune that juts into the fairway at the 230 yard mark. The golferwho elects to lay back from it, or even to its side, faces a tough approach, given the green’s defenses.

Best not to get greedy with the approach to the 16th. Sand right and behind and a slope front and left to kick balls away make the 16th green an elusive target.

This view from the right illustrates the tiny target of the 16th green.

17th hole, 145 yards; Having found so many of the holes as they now play today, Coore never worried too much about the 17th as he recalled Pete Dye’s adage that a one shotter can be built anywhere. In this case, there was a natural plateau that had been usedyears agoassmall dirt parking lot for people picnickingalong the bluffs. Cooreknew it would make for a fine green site. Throw in the wind, the change of direction, and the trees and their effect on the wind,and the author believes that this small 3,300 square foot target will be missed more timesthan one may think.Just as with the 17th and 18th at Sand Hills, its modest length is the perfect complement to the Home hole, which is the toughest par on the course.

The plateau that is now the 17th green was already there. Note the

18th hole, 450yards; A humongous finisher. The deep bunkers down the left are the best one can hope for should one’s ballhook in that direction. Though the hole is over dramatic terrain,Coore & Crenshawmassaged the land in the hitting area to make it less abrupt and provide the golfer with plenty of width so that good golf can be played. The green is the most exposed on the course and the golfer will never tire of judging the wind’s effecton the approach shot.

Beautifully cut from their surrounds, this pair of bunkers guard the inside route home off the 18th tee.

The thrilling approach to the Home hole.

From the months it tookto find the best routing towhen thecoursewas ready for play, Bakst gave Coore & Crenshaw the time they wanted/needed andhe was careful not torush the creative, free flowing process that would allow the best course to evolve on site. Bakst’s commitment to finding the best holes was evident when he was toldby his land planner that the clubhouse location behind the proposed 18th green and 1st tee was too small. Undeterred, he went to a second land planner whoconfirmed that there was indeed enough room. Bakst immediately told Coore to press ahead with the routing as planned.

The end result of this process and of having so many talented people on site formore than2 1/2 yearsisthat each holeisfull ofcharacter, the character of which highlights the naturalattributes of this uniquesite. Coore & Crenshaw’s approach at Friar’s Head brings to mind the words of Willie Park, who wrote that:

A golf architect must approach each bit of country with an absolute open mind, with no preconceived ideas of what he is going to lay out, the holes have to be found, and the land in its natural state used to its best advantage. Nature can always beat the handiwork of man and to achieve the best and most satisfactory results in laying out a golf course, you must humour nature.

Similar with Park’s nearby architectural masterpiece at Maidstone Golf Club in East Hampton, man will never tire of tackling the challenges laid out at Friar’s Head as theyare widely varied and based in nature.Such courses represent the zenith of golf course architecture,withman’s carefulinteractionwith nature yielding an environment that both invigorates and inspires.

If more owners and architects would learn from the patience that was demonstrated at Friar’s Head, thena second Golden Age of architecturecould be finally entered.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)