Four Seasons Carmelo

Uruguay

Green Keeper: Ricardo Meglonio

Despite the obvious allure of the pool and resort at Carmelo, the golfer is keen to take the five minute shuttle…

…to the golf course as it provides a unique environment in which to enjoy a game. This view is from the elevated tee of the 560 yard eleventh hole.

The beauty of a resort with less than fifty bungalows and suites is that the guest is assured of a tranquil environment. Of course, few such size resorts offer golf. After all, even if the resort is full, the golf course would be more than half empty. The Four Seasons resort at Carmelo, Uruguay is a wonderful anomaly, one that golfers are well advised upon which to take advantage.

Designed by Kelly Blake Moran and Randy Thompson, the golf course here at the Four Seasons Golf Club garnered immediate praise upon opening in 2001. Considered the finest course in Uruguay, a lead Brazilian golf magazine voted it the best course in all of South America in 2007. Despite such recognition, less than 4,000 rounds were played on it in 2006.

Yet, to the Four Seasons’ credit, they continually commit the resources so that Green Keeper Ricardo Meglonio can present the course in a first class manner as the resort appreciates the loyalty that the course stirs with many of its core visitors that return year after year.

How did such a quality design emerge here? In some ways, the story begins with Dick Wilson, considered by some including this author as the finest golf course architect for the twenty year period from the end of World War II to 1965. Pine Tree Country Club in Delray Beach, Florida, NCR Country Club in Dayton, Ohio, and Lucayan Country Club in the Bahamas are among his finest designs. A common feature throughout many of his designs is the angle he placed his greens relative to the fairways. No doubt Wilson learned how to do so while working on Shinnecock Hills and Indian Creek for master architect William Flynn.

Wilson’s work was highly sought after to the point where he had to rely on a talented team of associates to carry out many of his projects. Among this group of associates were Joe Lee and Robert Von Hagge and both went on to have successful careers of their own. In the case of Von Hagge, he left Wilson in 1963 to create his own firm. Boca Rio Country Club is a very fine example of his work and for some it even rivals Wilson’s nearby Pine Tree, a course famously praised by Ben Hogan.

In the 1990s, Randy Thompson met Kelly Blake Moran while both were working for Von Hagge on a project in Texas. The two became friends and remained in touch even when Thompson moved to South America. When Thompson uncovered the opportunity to build this course in Uruguay, he knew whom to call. Moran had just started his own firm in the United States. Appreciating it would take a year or two to develop a workload, Moran was happy to come to Uruguay to help his friend.

Given the low level of play that was forecast, the construction budget was a modest $2.5 million (USD). Other than the first and tenth holes, the holes were literally created from a swamp. Twenty seven hectares of continuous lakes were created with the resulting fill used to create the golf holes. Slightly over one million cubic yards were moved with nearly one third of that being used in a triangle between the fourth, fifth and eighth holes.

Architect Randy Thompson putts out on the eleventh green. Behind him is the swamp from which this well thought-out design emerged.

Given the background of the two architects, the fact that there is a considerable amount of Robert Von Hagge’s and Dick Wilson’s influence in the design comes as no surprise. This influence particularly manifests itself in the green complexes where many are broader than they are deep. Combined with the bunkers which are invariably cut at the edge of the greens, the golfer is given a number of shallow targets. Without doubt, the golfer who can hit high soft approach shots enjoys an advantage.

One of the finest greens is found at the 375 yard sixth hole. This gull wing green is two feet higher on both its left and right ‘wings’ than its lower middle portion. The green is over fifty yards wide but only the middle portion offers much of a target in terms of depth. Place the day’s hole location on either wing and brave (or foolish) is the golfer who attempts to get his approach shot close. Place it in the middle and many of the resort’s guests find a potential birdie hole. As Randy Thompson says, there are only so many ways to crumple a piece of paper. By that, he means there are only so many ways to build an interesting green from scratch and both he and Moran take great pride in this creation.

As seen from the right of the sixth green, the green is far broader than it is deep. The challenge in hitting one ‘s pitch close to a hole location on either wing is evident.

Typical of Four Seasons service, they happily accommodate the request of several returning groups to ‘hide’ the hole locations during their three day visits.

Holes to Note

2nd hole, 445/410 yards; For a course that emerged from a swamp, the golfer delights in finding interesting contours throughout many of the holes. The second is a particularly fine example of very good land movement from the tee to green.

As seen from the second tee, the crest in the second fairway seems natural but in fact was created by Moran and Thompson.

The attractive approach to the second green is played from the high point in the fairway to the high point of the putting surface.

3rd hole, 190/165 yards; This green complex would be right at home at Pine Tree, high praise considering that many (including Ben Hogan) consider it to be Dick Wilson’s finest design. The built up green pad gives the front bunkers depth but it is the boomerang configuration of the green itself that gives the golfer fits.

The breeze bending the flag is off the twenty five mile wide Rio de la Plata that separates Carmelo, Uruguay and Buenos Aires, Argentina.

As seen from the right, the boomerang configuration of the third green means at least two clubs more are required for one

4th hole, 420/390 yards; Alister MacKenzie was a huge fan of doglegs. In his day, the inside of a dogleg was often covered by bunkers or scrub, leaving the golfer with wonderful options to puzzle as to what line to take from the tee. In modern times, the golfer finds the inside of too many doglegs protected by trees, squashing the strategic merit from the tee ball. Not so here as only bunkers cut into the far hillside guard the inside of this dogleg right. The tiger dearly likes to carry the far right bunker because 1) the ground just past it gives his tee ball a nice kick forward to the green and 2) the green is much broader than deep, pointing to the desire to have a short iron in to such a target.

A well struck drive over the bunkers on the inside of the dogleg leaves this manageable pitch. The golfer who hit straight off the tee and didn’t get the kick forward off the bunkers is likely forty to sixty yards back, wishing the green wasn

5th hole, 440/400 yards; The fairway’s right to left cant created by Moran and Thompson makes the hole. The farther the golfer steers away from the lake down the left, the more pronounced his stance becomes with the ball above the right handed golfer’s feet.

The white flag is seen in the distance and the task off the fifth tee seems obvious: long and anywhere but left. However, after a round or two, the golfer appreciates that the better stances are afforded closer to the lake.

7th hole, 205/160 yards; Lakes appear on fifteen of the eighteen holes; only the first, third, and tenth holes are devoid of any water hazards. If the water was used in an aggressive, heavy handed manner, the golfer would quickly tire of the sameness of the challenge. Such is mercifully not the case as Moran and Thompson used the water in every imaginable manner possible, frequently – to their credit – with it essentially out of play for all but the absolute worst shot. Indeed, of the fifteen holes with water, this is the sole one whereby the water directly fronts the green. Too many modern architects use water as a crutch when they start to run low on design ideas. Clearly, Moran and Thompson’s restrained use of water shows they never lacked ideas when building Carmelo.

8th hole, 565/560 yards; One of the great holes in South American golf, the fairway parallels the lake for the first four hundred and thirty yards before wrapping around its top and heading to the green. This candy cane shaped fairway leads to all sorts of interesting playing angles, regardless of one’s ability.

Even if the golfer reaches here at the top of the lake in two, he still faces a challenging approach shot of 130 yards.

9th hole, 445/420 yards; The bunkering schemes off the tees are used to great effect at Carmelo. In this case, with a lake down the left, the architects wanted to avoid a hole that felt similar to the fifth. Thus, Moran and Thompson placed two long bunkers in the hitting area perpendicular to the lake. In conjunction with another bunker on the high right side, the fairway is transformed from being a straight one ala the fifth to an ËœS’ shaped one.

A glimpse of the bunkers down the left is afforded the golfer from the back markers of the ninth tee. The green is in line with the clubhouse. As tough as it may be, the golfer must avoid the line of charm and make himself aim toward the right edge of this photograph.

Dick Wilson made his reputation in an age of golf course architecture whereby aerial approaches dominated the design process. The ability to hit a high approach is crucial when the hole location is set on the right of the ninth green.

12th hole, 375/350 yards; The widest fairway on the course greets the golfer, despite the addition of a central waste area by Randy Thompson three years ago. At over eighty yards in width, every golfer is bound to hit it. However, off to the right, across the elbow of the lake and marsh is the white flag blowing in the wind, luring the golfer in that direction. The flag is only 280 yards from the blue tee on a direct line. All kinds of greedy thoughts creep into the golfer’s mind, generally the start of a high score! Good golf course architecture goads the player into decisions that he later rues, with this hole being a fine example.

The view is from the twelfth tee with the white flag acting as a siren, wooing the golfer into potential trouble. If able to resist, the smart golfer hits straight down the fairway, leaving himself a relatively simple pitch and a chance for birdie. Conversely, one mighty blow and the golfer may be putting for eagle…

14th hole, 415/400 yards; Two of the design’s primary attributes in terms of how flexible the course can play are highlighted at this hole. First, the placement of the tee pads greatly influences the hole’s difficulty. From the back markers, the carry off the tee is over water to a fairway at an oblique angle to the tee. Meanwhile, the rest of the tee markers are straight in line with the fairway, nearly removing the water as a hazard with which to contend. Secondly, the configuration of the green complex provides a wide range in hole locations. As we see below, a back left tongue provides for one of the hardest hole locations on the course with which to get close. Any resort course must have the flexibility to accommodate a wide range in playing skills, and such is the case at Carmelo.

Only the back markers have the golfer hit over water to the fairway; from the shorter 400 yard markers, the golfer hits straight down the length of the long fairway with the water out of view. The green’s white flag is visible on the left.

The ideal drive leaves the golfer on the inside of the dogleg left with this view of the green. This particular hole location is extremely well hidden – only fools chase after it. Meanwhile, hole locations front right leave the golfer with higher ambitions.

15th hole, 400/360 yards; A bigger version of the twelfth hole, the temptation to cut over the elbow of the lake is great. The ‘S’ shaped lake snakes along the right of the entire hole. Its random, winding appearance makes it appear far more natural than if Moran and Thompson had settled on building a big oval or circular lake.

From the dogleg right fifteenth tee, just how much should the golfer bite off? The answer surely depends on the state of his game as well as the day’s wind.

Assuming one avoids the water off the tee, the walk down the fifteenth fairway is made all the more enjoyable by the view of the horses on the far side of the lake. The sense of truly being in a remote place, far from all worries, is complete.

16th hole, 530/495 yards; Visual deception helps keep a course fresh. Without it and with all features laid in plain view, the courses secrets are revealed to the golfer after only a few rounds. If a course is that easy to get to know, why bother coming back? As seen throughout this design, the subtle land movement that Moran and Thompson created adds immeasurably to the fun and challenge of a game here. In this case, a nest of bunkers built into the crest of a gentle rise in the fairway 120 yards from the green obscures the view of the putting surface. If the golfer is unable to get past these bunkers, the view of only the flag without the putting surface creates depth perception problems for one’s approach.

Hard to believe but the bunkers in the foreground are one hundred yards from the flag.

The 220 yard seventeenth and 440 yard eighteenth provide the classic big finish so sought after in Wilson’s day. A review of the photographs in this course profile shows how the course teases the golfer into getting out of position. For instance, he just misses the second flag to the left, leaving a flop recovery shot out of Bermuda grass from well below the green. On the third, he chases after the back hole location in the boomerang green only to pull his tee ball slightly into the back bunker. Just a few more yards to the right under either scenario and the golfer has a short putt for birdie. Such incidents of just slightly having missed a great shot occur throughout the round. Importantly, never does the golfer feel unduly punished – the water is mostly well out of play and the bunkers are rarely deep. Instead, the golfer is encouraged to have a go at some of these interesting hole locations as well as learning when to act with more prudence. Over all, the golfer enjoys the chess match with the two architects.

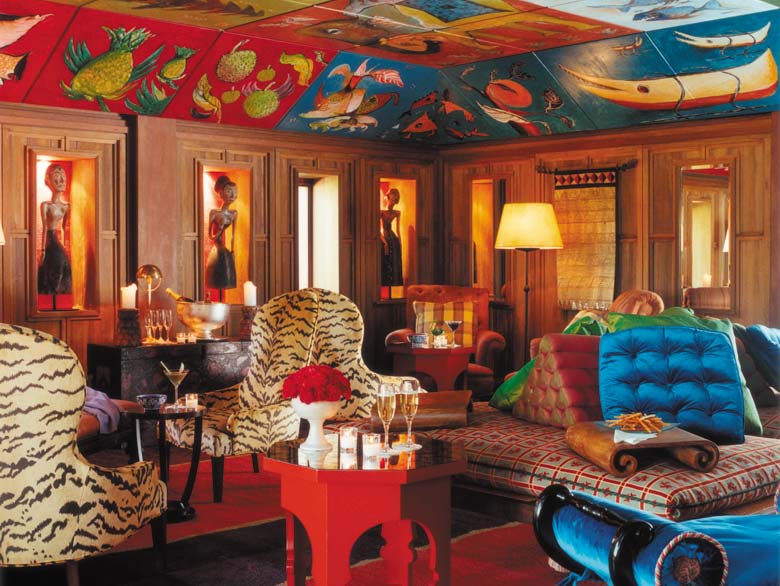

As fun as the round, the best may be yet to come back at the world class resort. The Balinese artifacts collected by Laith Pharaon set the tone of unhurried luxury. Relaxing by the pool during the summer months of November through March will certainly not make any traveler from Europe or North America wish they were home. Indeed, if life is well, thoughts of booking one’s return trip to this resort may be the most pressing decision.

Congratulations to the Four Seasons for their presentation of both the course and the resort. The course was built for $2.5 million (USD), in part because no big name architect fee had to be paid. Instead, the Four Seasons got what matters most: two talented architects who stayed on site and poured time and thought into every hole. The result is there are no weak holes. Though some of the Four Seasons courses have had larger budgets (especially the excellent Jack Nicklaus design at the Challenge at Manele in Hawaii), this course is one of the three or four best within the Four Seasons group of golf courses.

By keeping construction costs down, the Four Seasons can contemplate using this model in other such remote locations. Though the foot traffic will never be great, the loyalty that the patrons who visit Carmelo will show to the Four Seasons brand around the world provides its own satisfactory return.

Laith Pharaon’s unique flair dominates the decor within the resort.

The bungalows at Carmelo are the perfect retreat.

The quincho, a private gazebo along the beach of the Rio de la Plata, or the nearby three level swimming pool are idlyllic spots to relax after one’s golf game.

The End