Of late, for a variety of factors—environmental and economic being foremost among them—renovations and restorations have been all the rage in the golf world, particularly at “golden age” clubs that had been neglected and overgrown, or disfigured and sapped of their unique character by callous architects intent on transforming the gems left by their predecessors from the first part of the 20th century into “modern, championship tests”.

Like most forms of art and design, golf course architecture is, at its core, a practice of imitation, trends, and cycles. In most cases, a single, seismic newcomer can be identified as the catalyst of each redirection in ethos. As this article will proceed to highlight, this current wave of restoration and renovation is merely the latest sway in a tide that has shifted from one extreme—that of the “penal school” of architecture—to the other—that of the “minimalist movement—throughout, roughly, the last 60 years.

- Beginning with Trent Jones’ work prior to the ’51 Open, virtually all trace of Ross’ genius at Oakland Hills in Detroit had been eliminated… (photo credit: Wikipedia)

- …At least until Gil Hanse’s team restored the Donald Ross Oakland Hills

Robert Trent Jones’ warmly received work at Oakland Hills, near Detroit, in preparation for the 1951 U.S. Open, eventually won by Ben Hogan who famously proclaimed in his victory speech that he had “brought this course, this monster, to its knees”, is commonly cited as the beginning of the “dark age” of golf course architecture, a period of roughly thirty years during which linear, penal, and one dimensional tests were considered the gold standard of golf course construction, maintenance, and presentation—for proof of this preference see the roster of major championship hosts of the 1970s and 1980s: Champions, Hazeltine, Atlanta Athletic, Medinah, Bellerive, Kemper Lakes, Firestone, and Shoal Creek. And a scan through the various top 100 lists published during this timespan provides further: Muirfield Village ranked as the 6th best course in the U.S. by Golf Digest in 1985; Oak Tree National ranked 16th (now unranked); Butler National ranked 19th (now unranked); Colonial ranked 22nd (now unranked); Medinah ranked no lower than 13th throughout the decade; and, perhaps most notably, Shadow Creek debuting as the 8th ranked course in 1993.

- Medinah’s No. 3 course, host of a litany of noteworthy events (photo credit: Golf Digest)

- Kemper Lakes, host of the 1989 PGA Championsip won by Payne Stewart—thankfully and unsurprisingly has not hosted another major since (photo credit: Troon)

This partiality towards demanding and exacting, yet allegedly “fair” tests of golf—“a hard par, but easy bogey” as Trent Jones put it—remained the predominant one in North American golf course construction and popular taste until about the mid 1990s, when Bill Coore’s and Ben Crenshaw’s uber-natural, endlessly strategic, and quirky Sand Hills, in tiny Mullen, Nebraska, burst onto the scene with rave reviews, wide eyes, and epiphanic “ahas”. Indeed, it must be said that Sand Hills was not the first modern course to again prominently feature these core tenants of golden age architecture, nor was Coore & Crenshaw the first contemporary firm to again implement them throughout its catalogue; however, just as Oakland Hills spawned countless imitators and influenced all of golf course architecture—both as an example and something to subvert against, namely in the case of Pete Dye—after that seminal Open of 1951, Sand Hills’ impact was so great that it changed the practice and remains just as forceful, if not greater, today. On GolfClubAtlas, Ran Morrissett claims that “steeped in history, St Andrews has a spiritual hold unlike any other, with golfers leaving there more invigorated than ever by the joys of the game of golf. For many, the course in the United States that offers a similar reconnection to all the game’s best attributes is Sand Hills.”

One man who had such an experience was Mike Keiser, then a budding developer with only the Dunes Club, a private nine hole course along the south shore of Lake Michigan, in his portfolio. After an inspirational visit to Mullen, followed by a lengthy search for the ideal piece of land, which he eventually stumbled upon in Southern Oregon, he applied many of the same principles—walking only, firm and fast conditions, playability, wide fairways—to his publicly accessible Bandon Dunes Resort, a venture that launched the careers of David Mclay Kidd, Tom Doak, and, even, Coore & Crenshaw into new stratospheres of recognition. In fact, even the primary leaders of the “penal school” of architecture (Trent Jones, Tom Fazio, Dick Wilson, Jack Nicklaus), as it is commonly termed, slowly started to adopt some of the concepts and principles of their rebellious competitors, widening fairways to introduce different angles of play, adding short grass around the greens, moving less earth, and eschewing highly manicured areas around the playing corridors. Here, a comparison between a course Fazio built early in his career—say Wade Hampton or The National Golf Club of Canada—to one he built more recently—say Gozzer Ranch or Congaree—spotlights the influence of the “minimalist movement” even on he, once the most artificial, groomed, and pristine of architects.

The postage stamp par 3, 17th at Los Angeles Country Club’s North course (photo credit: Golf Tripper)

To narrow down the current “golden age of restoration” to a single precipitant is, at least according to this author, more difficult than with the “penal school” or the “minimalist movement”. With good reason, many will point to Coore & Crenshaw’s restoration of Pinehurst #2—and the subsequent praise their work received from historians, paying amateurs, and professionals alike when it hosted the men’s and women’s U.S. Open in back to back weeks in June 2014—as that potential catalyst; however, their work in the sandhills of North Carolina is rather akin to Gil Hanse’s on the North course of the Los Angeles Country Club, which began a few years before. There, Hanse similarly ripped out acres of rough, re-introduced fairways that morph seamlessly into unkempt native playing areas, rumpled bunkers, and, for lack of a better term, roughened and scruffied the presentation of the course. Some might also cite Oakmont’s controversial decision to raze nearly all the trees on its property in the 90s.

- The 4th at Pinehurst Resort’s No. 2 course during the 2005 US Open. (photo credit: Salt Lake Tribune)

- The 4th at Pinehurst No. 2 as it plays today

Important as these efforts were, I believe, however, that the predominant driver of this so-called golden age of restoration and renovation has been the rise of the countless websites and social media platforms dedicated to architecture and to the history of the sport, notably GolfClubAtlas, The Fried Egg, and, hopefully, our site, one day. After all, there is something very American, in truth human, about wanting to better your neighbors, about desiring the shiny new toy on the block, and these platforms, on account of the pictures shared and the write ups written on them, easily allow the general public to see, with concrete and comparable proof, the wonderful effect that a thoughtful, historically attentive restoration can have on a worn, tired course, or the eye-opening outcome a bold, innovative, and sweeping renovation can produce on a formerly mundane, unimaginative one. When the various social-media platforms share the work done at a course up the highway, or elsewhere in the county, or even in the same tier of rankings, it commonly provokes a desire to produce likewise at other, rival clubs, often for fear of falling behind or, even, of losing members—in layman’s terms, it creates a domino effect. Furthermore, the majority of these transformations, despite their hefty initial cost, have been financial home-runs. For proof of concept, one needs to look no further than the Pinehurst Resort, which was always busy but is now bustling at an unprecedented level—or, on the private side, Moraine in Ohio, Sleepy Hollow in New York, Old Town in North Carolina, and Pasatiempo in California, all of which have been similar success stories, ranking, membership, and satisfaction wise.

The brilliant 3rd at St. George’s, restored by Ian Andrew and Tom Doak

Unfortunately, this wave of renovation and restoration has arrived only as a gentle, lapping one, rather than a tsunami, upon the northern shore of the border; the initial motivation of this article was, in fact, to try to understand and work through why we are lagging so far behind. In the end, I’ve produced three reasons that, I think, explain why we have not yet felt its full force.

The first, and likely foremost, reason is the lack of exposure our courses receive, especially those in the more remote areas of the country—i.e. anything away from the G.T.A. and, maybe, Vancouver, basically. Not to disparage too harshly our leading print publication dedicated to golf, which, out of respect, will remain nameless, but its ever-decreasing pages are now largely filled with basic golf tips, sponsor-biased reviews of the latest equipment, formulaic stories about tour golf, and, often and unfortunately, regurgitated exposes on vacation destinations in the U.S. The few pages actually dedicated to our golf courses nearly always focus on the same big name offerings which we have all heard and read about incessantly over the past twenty years: expensive public courses in or near the G.T.A, Cabot, P.E.I., the Muskokas, Whistler, Banff, and perhaps Jasper. And yes, I fully get the need to shift copies and attract clicks, no easy feats in this era, and that few are interested in reading, for example, about a Walter Travis/ C.H. Allison public course in Shawinigan, or a once great Stanley Thompson course fallen on hard times in Montebello, or a surprisingly little known Alister Mackenzie course in Winnipeg, or the wonderful array of municipal courses built by A.V. Macan in Vancouver.

Apart from that publication, Robert Thompson, whose blog Going4theGreen, which has not been updated in a handful of years but is thankfully still available, is a treasure chest of keen, astute, unbiased, and critical writing on a wide variety of subjects pertaining to golf in Canada and its primary actors, the kind that is, regrettably, all too rare nowadays. Ian Andrews’ blog, found simply by searching his name in Google, similarly provides ample illuminating content; as evidenced by his restorative and renovative work at St George’s, Cherry Hill, Maple Downs, or Laval-sur-le-Lac, there are few, if any, more attuned, more caring, and more knowledgeable about the evolution and direction of golf in this country. For the sake of brevity, I am omitting to name a few other fine Canadian writers: here, Lorne Rubenstein, a true pioneer, whose work, however, I am regrettably naive to, springs to mind immediately. Yet they are too few, are too far between, and are not enough read. At risk of sounding like a marxist preaching about governmental injustices from a raised platform in central square, social media—instagram in particular, it seems—is a tabula-rasi waiting for Canadian creators to give our noteworthy courses the same level of exposure as those south of the border receive (and, no, I do not mean Don Valley). With such exposure, my hope, my steadfast belief is that a domino effect will truly begin up here, the way it has down there.

Ian Andrew yet again beautifully restored Cherry Hill Club near Niagara/Buffalo, and today, the course plays as Walter Travis intended.

The second reason delaying the much-needed waive has to do with something deeper concerning the Canadian psyche, the Canadian mindset. Here, rather than provide my own amateur diagnostic, I will instead defer to Northrop Frye, whose critical writing on Canadian culture remains, in my estimation, still the most relevant and important and shrewd produced by a Canadian intellectual. In The Bush Garden: Essays on the Canadian Imagination, his best-known collection, he suggests that “historically, a Canadian is an American who rejects the revolution”, and that “there is in Canada, too, a traditional opposition to the two defects to which a revolutionary tradition is liable: a contempt for history, and impatience with the law” (Frye 14). This sentiment, this fear of revolting against the past, against our forefathers, can, at least in my experience, be applied to the complex and often edgy workings within the membership and hierarchy of most country clubs, where the boards and/or the individuals in charge have commonly been in those positions of influence for decades, and are thus reticent about accepting proposals put forth by new-comers, or those willing to buck the status quo. Golfers are, if anything, creatures of habit, of comfort, and to accept extreme change is, as everyone knows, difficult, particularly to things we hold dear: most of us become spiritually and emotionally attached to the course we play regularly, so it is hard to bear having its flaws and shortcomings laid on a platter. Not to venture too far into non-golf commentary, but Americans have, historically and socially, been more willing and ready to cleanly sever all ties to their past, and, for lack of a better term, to charge head first into unventured territory, to “go west young man”; whereas we Canadians always seem do so with one eye towards tradition, towards conservatism.

Furthermore, architectural deterioration, such as the shrinking of greens, or the encroachment of trees, or the failure of bunker faces, is often difficult to detect when one sees it occur slowly and gradually over an extended period; again speaking from experience, it is almost as if we become used to it, and thus find ways to justify it—“well, ya, but it’s been this way since I can remember”; “well, the overgrown tree forces the player to shape it”; or “well, it’s a short par 5, so the green can be a little smaller”.

Tying the second reason back to the first, social media and the various online resources have made many of the previously difficult and/or expensive to procure books and essays about this niche-subject readily available: most of the classics of the genre are now available online for free, and the previously mentioned websites are full of short, eminently readable pieces. As a result, many golfers—especially the younger, social media savvy generation—are now better aware of the principles of good architecture and about the history of their respective clubs; in turn, they begin to populate the boards, pushing out the old guard and ushering in a new, revolutionary one. Really, there is no excuse to be ill-informed anymore, yet too many Canadians, particularly those in positions of influence at our historic clubs, still are, unfortunately.

- The current 6th at Chateau Montebello’s Golf Course…

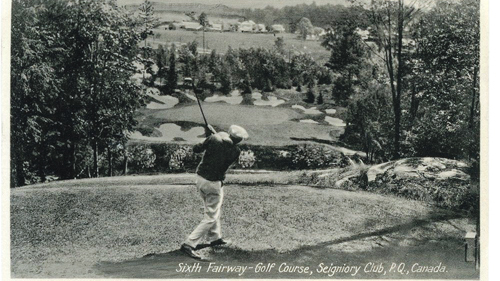

- …And what it used to be when it was the Seignory Club and Stanley Thompson’s 6th best course. There is perhaps not a better candidate for a restoration in Canada. (photo credit: L’actualité)

The third and final reason is the lack of a true catalyst, a Canadian catalyst, the way Oakland Hills, or Sand Hills, or Pinehurst #2, or L.A.C.C. acted as the precipitants of their respective movements. Massively successful renovations and restorations are hard to find in Canada, the best example likely being Martin Hawtree’s work at the Toronto Golf Club, which, by all accounts, is quite good; yet the club shuns about any and all publicity. There are a few others, too: the work of Andrew in collaboration with Tom Doak’s firm at St George’s, which will be on display during next year’s Canadian Open (if it happens), is one potential kick-starter; the same applies to the work being done by Martin Ebert and Tom Mackenzie at Hamilton, set to host the Canadian Open in 2024.

A golden opportunity was missed in the early part of the previous decade when Laval-sur-le-Lac and Golf Canada were unable to finalize the details to bring the 2014 Open to the Blue Course, where Andrew entirely re-imagined a formerly bland, unimaginative Graham Cooke course into one of the country’s most architecturally interesting layouts. Among all the renovations and restorations done in Canada, this is probably the closest example we have to a complete, Moraine-esque or Sleepy Hollow-esque overhaul, and his work there would have shone on television while amply testing the world’s best.

Thompson’s Banff Springs, still among the foremost courses in the country, despite the unfortunate routing change done for the sake of accommodating the new clubhouse.

What needs to happen, though, for the wave to kick into full gear, is for a mid-end, previously little known—and preferably public—course to simply say “let’s do it” and pony up however much cash is needed to completely transform their club beyond recognition; then, of course, for our media outlets to aggressively promote the changes and their positive effects.

We may as well get this out of the way now: no, Fairmont Hotels is not going to divvy the cash necessary to completely fix Banff and Montebello anytime soon, nor will Parks Canada for Highlands Links.

With this in mind, I have what I think is the perfect option: the Thompson course at Lachute near Montreal. As it stands, the course is quite good, solidly among that group of about 50 courses which could be ranked anywhere from 80th to 130th in Canada, depending on one’s preference. Most promising, though, is that the club is currently being run by a savvy, architecturally attuned G.M., Ben Painchaud, whose passion and vision are exciting. Under his direction, good, thoughtful work has been done the last few years, but it is more a step, rather than a leap, in the right direction. And the Montreal area, only a fairly short drive away, is rife for a truly great public option—one could argue, in truth, that aside from Lachute there is not another public option near the second biggest city in Canada that grades out above a Doak 4.

The opening approach at Lachute’s Thompson course, a fine Stanley Thompson layout near Montreal.

Golf has never been more popular. If Lachute was to bring in, for example, Ian Andrew, or Andy Staples, or someone else of that ilk, and let them go wild, I am sure that it would not only be a home run for the club, but also pave the way for others to do the same.