I have a draft I have not quite finished that outlines the trends of Canadian golf architecture, and why it seems to be looking forward to exciting days. Renovations are in proper hands now, whether that be Rod Whitman’s firm at Brantford, Jeff Mingay & Christine Fraser at Beaconsfield, Ian Andrew at Edmonton, among other examples. New architects like Trevor Dormer are doing their thing, shapers like Josh McFadden and Ben Malach are kicking around the industry. Riley Johns is still trying to springboard off the back of the successful Winter Park, although a consulting job in Ireland and a new nine hole golf course on the ocean in the Florida panhandle might do it. Overall, it seems like golf has turned a corner in Canada, at least from where I’m sitting.

While new builds are still rare, there are a couple examples either going, or about to go. The architecture community is stronger than years past, and it seems like interest in golf architecture is growing. Granted, golf is too, but I digress. I truly believe Canada is seeing the light at the end of the Dark Ages tunnel, where Les Furber, Graham Cooke, Darrell Huxham and more continued to vandalize landscapes for their layouts.

Some courses did not have the luxury to escape that era, however. In fact, numerous courses went under the knife and never came out the same following the death of Stanley Thompson in 1953. Canada heavily benefitted from the Golden Age of Golf Architecture, just like the United States. H.S. Colt, C.H. Alison, Stanley Thompson, Willie Park Jr., Albert Murray, Donald Ross, Tom Bendelow, Alister Mackenzie, A.V. Macan, Herbert Strong, Devereux Emmet, A.W. Tillinghast, and more all built golf in Canada, but very little of it remains in its purest form. Post-Thompson, architects and greens committees were not kind to these layouts, and we pay for it to this day.

One of those courses is Herbert Strong’s Manoir Richelieu in the charming town of La Malbaie, Québec.

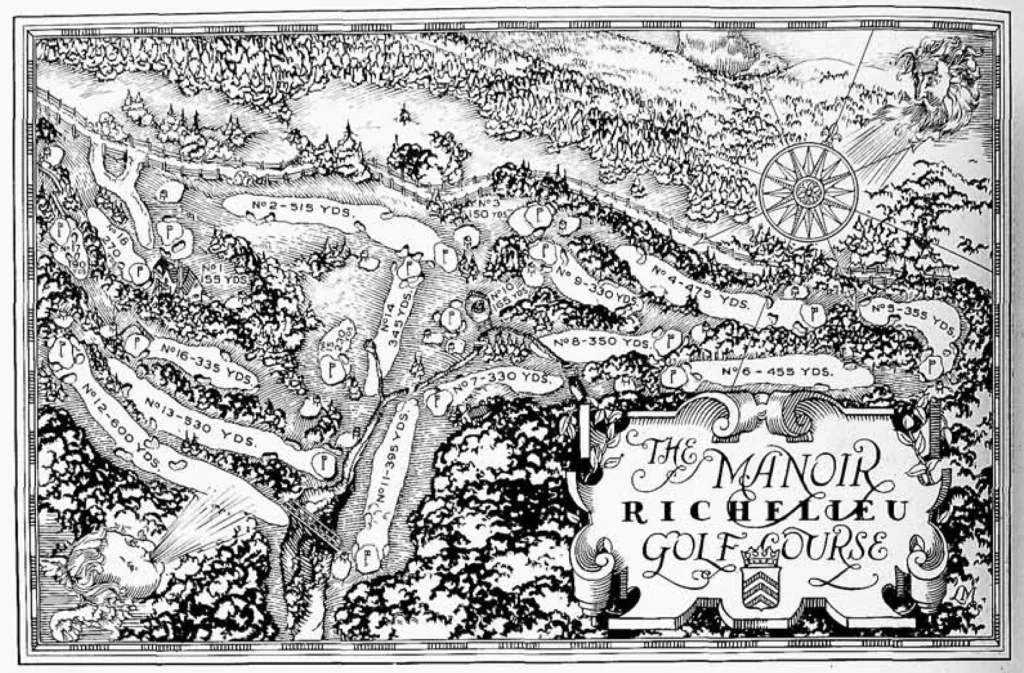

Inaugurated by US President William Taft, who spent his summers nearby, Manoir Richelieu opened in 1925. The golf course sits into a hilly piece of property overlooking the St. Lawrence River, with English architect Herbert Strong weaving his routing up and down the hillside, but not without its challenges. The golf course was rather… unconventional. It opened with a par 3, and by the third hole, you had played the front nine’s one-shot holes. The back nine also begins with a par 3, features back-to-back par 5’s at the 12th and 13th, and ends with a drivable par 4. Nevertheless, The Canadian Golfer, the main golf publication of its time, wrote in their September 1925 issue, “There is a splendid variety here of one, two, and three shot holes—none better in the country.” By 1925, Jasper, Royal Colwood, Hamilton, Royal Ottawa, Mount Bruno, and Toronto were the main courses at the time, as well as courses that no longer exist, such as Royal Montreal’s South course and York Downs. This is a big claim given the quality of golf at the time, but one that holds up under further examination.

IT’S A HARD COURSE (but who wants an easy one?) a sporty course and very beautiful. The Canadian Golfer, May 1931

| 1. 155 yards, par 3 | 7. 330 yards. par 4 | 13. 530 yards, par 5 |

| 2. 515 yards, par 5 | 8. 350 yards. par 4 | 14. 345 yards, par 4 |

| 3. 150 yards, par 3 | 9. 330 yards, par 4 | 15. 320 yards, par 3 |

| 4. 475 yards, par 5 | 10. 165 yards, par 3 | 16. 335 yards, par 4 |

| 5. 355 yards, par 4 | 11. 395 yards, par 4 | 17. 190 yards, par 3 |

| 6. 455 yards, par 5 | 12. 600 yards, par 5 | 18. 270 yards, par 4 |

| OUT: 3,115 yards, par 37 | ||

| IN: 3,060 yards, par 35 | ||

| TOTAL: 6,175 yards, par 72 |

For classic standards, 6,175 par 72 was a good length, but certainly not long (though it was difficult, with a course record of 71 in 1928). For contrast, Hamilton in 1915 opened at roughly 6,400 yards (par 70) and was considered monstrous. The normal length and unconventional routing did not stop the accolades from rolling in, however. As Ralph Reville wrote in The Canadian Golfer, “This Manoir course is admittedly one of the finest resorts in America. Mr. Strong personally thinks it is his masterpiece, and I am inclined to agree with him.” For an architect with golf courses like Engineers (NY), Canterbury (OH), Saucon Valley (PA), Ponte Vedra (FL), and Inwood (NY), this is certainly a high claim.

Strong’s architecture is heavily reliant on his greens, which are often aggressively contoured, unique, and borderline over-the-top (even back in the 20s, let alone today’s standards with the speeds golfers are obsessed with). Like Walter Travis and Devereux Emmet, his architecture is underrated against the big name architects like Ross, Tillinghast, or Mackenzie, but his catalogue is smaller in not only size, but exposure.

“The scenery surrounding the Manoir Richelieu GC at Murray Bay is the most impressive setting for a links of which I have knowledge. The chief task I faced was to build this natural beauty into every possible feature of the place. No designer could have more varied or lavish material to work with. Herbert Strong

Given the quote above, Strong was rather enthralled by the property, but it seemed he was rather proud of the golf course, often listing it third in his advertisements in The Canadian Golfer, behind Enginners and Inwood, and ahead of Lakeview, Canterbury, and Saucon Valley. Lakeview was rather famous at the time and fresh off hosting the 1923 Canadian Open and regarded as “the hardest test of good golf in the Dominion” (Canadian Golfer, March 1927); Canterbury is generally celebrated as his best effort remaining in our day and age; Saucon Valley, near Philadelphia, was also held in high regard. By 1929, Strong was advertising Manoir Richelieu on top of his other golf courses.

Like most golf courses, post-World War Two was not kind to this property, but who are we to blame anyone for prioritizing something other than golf after the war. So much, in fact, that golf writers had changed their tune. No longer was Manoir Richelieu this wonderful golf course to go see. As Bradley Klein writes on Golf Club Atlas, it was basically waiting to be put out of its misery: “Manoir Richelieu offers a dramatic setting, but Herbert Strong’s original layout was badly routed, with about 6,100 yards squeezed out of too many terraced holes and slopes to fairways and greens that would have been simply unplayable today. It didn’t help that a renovation project in the 1960s, as I recall, had eased some of the cross-fire dangers but led to some very weak holes.”

In 1998, Canadian Pacific Hotels Fairmont purchased the hotel and accompanying golf course. Immediately, they hired Darrell Huxham to add nine holes, now named the St. Laurent nine, which opened in 2000. In 2003 and 2005, Huxham renovated the existing Herbert Strong golf course, which now bears the names of “Richelieu” and “Tadossauc.”

Huxham’s résumé is not one you would expect to be tasked to renovate a golf course of such acclaim, even further considering Strong’s architecture. For those unfamiliar, his catalogue includes La Tempête in Québec City, Kingswood Park, Le Maitre, and Country Club of Vermont. Given his inexperience with historically important, dynamic architecture, it is no surprise to find out that Manoir Richelieu, as so many used to know it, does not exist anymore.

The St. Laurent nine is brand new, and really, other than the 5th hole on Herbert Strong’s routing, does not affect the old layout. Nevertheless, it is a certified “Doak 0,” a golf course so contrived and unnatural it may poison your mind (this is Tom Doak’s actual definition in The Confidential Guide to Golf Courses). Huxham himself can be remembered for mentioning that the property was so extreme he didn’t have to worry about how far apart the holes were because everyone would cart. He is right, but it doesn’t justify the holes. The opening two are stunning and some of the most beautiful holes on planet earth. After that, it feels like you play down (and back up) a ski hill as it falls into the St. Lawrence. Oddly enough, this half of the golf course SCOREGolf chose to rank for a decade on their Top 100; on this site, our panel put the Richelieu & Tadossauc combo in the Top 100 Public, albeit closer to the bottom of the list.

For me personally, I have no issues with the St. Laurent nine existing. Actually, from an operations standout, it is perfect. A third nine that is far more dramatic and scenic to compliment the old school, quirky Strong course. Even if my growing architecturally pompous attitude cannot accept the St. Laurent from an a technical point of view, there is no denying the juxtaposition between an old Herbert Strong and a new, wild, rambunctious modern nine holes creates an interesting dynamic for resort visitors. Not only that, but it is easily among the most scenic nine holes of golf in Canada. If it doesn’t affect the old layout, no issues!

The problem is that beautifully juxtaposition between new and old does not exist. Instead, visitors will be quick to realize there is no old school quick here. No charm or interest remains. A monotone, Darrell Huxham golf course sits on top of the old golf course, even if it does use some of the original corridors.

Roughly 70% of the Tadossauc/Richelieu golf course uses the original corridors Strong laid out, including the opening four holes + 8 & 9 on the Richelieu nine (below, indicated by “R”), and the opening six + the 8th on the Tadossauc nine (“T” below). This is a large portion of the golf course, yet one would not be able to tell one of golf’s unheralded Golden Age architects was here prior to Huxham.

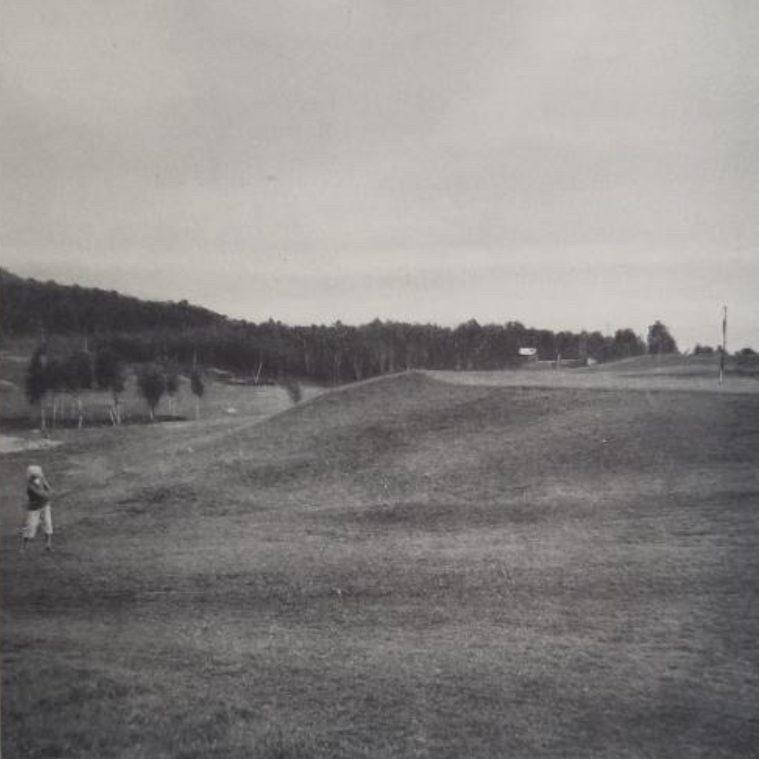

There are elements remaining—bread crumbs, of sorts, for those with a keen eye— to find scattered throughout the golf course. Even after Huxham’s heavy hand on Herbert Strong’s routing, you can see the remains of the drivable par 4, 18th, now the 4th on the Tadossauc nine. After playing the drivable par 4, which is still reachable at ~320 yards, the golfer will walk past the old clubhouse to the old 2nd hole (very top image) that tumbles down into the valley. Not-so-surprising, this is the strongest stretch of golf on the entire property. It is a difficult walk, but like Capilano or Highlands Links, a gratifying one filled with stunning views at almost every turn.

One of the Finest on the Continent of America—Links have a Most Superb Setting and Every Hole has its Distinctive Charm

The Canadian Golfer, June 1926

Aside from that, it takes awhile to find any Golden Age charm throughout the rest of the Tadossauc/Richelieu combo. Sure, the 5th & 6th on Tadossauc remain in Strong’s original sequence and corridors, but they lack the excitement. All of Herbert Strong’s greens are gone, and not for the better. Very monotone modern greens with very little character or interest is found on the surfaces, with seemingly very little slope. If there is, you would not be able to tell.

The next taste of excitement and intrigue comes at the 2nd hole on the Richelieu course, a blind tee shot over a rock outcropping to a very wide fairway. This would have been the 9th hole of the original routing.

Following up on a significant upgrade to the existing Quebec golf course, the addition of a new nine under the watchful eye of renowned architect Darrell Huxham, the Club de Golf Le Manoir Richelieu in Quebec is now home of 27 world class holes of golf. While keeping the essence of the original design, Darrell Huxham managed to showcase the natural beauty and esthetics of the Charlevoix region. Fairmont Manoir Richelieu’s website

Perhaps most interestingly, a claim from Ben Cowan-Dewar (CEO, Cabot Collection) on Golf Club Atlas, who said his grandfather was very high on Manoir Richelieu: “My grandfather was very fond of Richelieu, placing it among Thompson’s best (somewhere in the middle I recall).” If we count the Thompson Five and Manoir Richelieu, that would put it inside the Top 10 in the country (according to Beyond The Contour‘s 2022/2023 list), somewhere near Capilano (3rd best Thompson and 5th best golf course in the country). It is difficult to speculate exactly where a restored Manoir Richelieu would fall, but the point is: it used to be much more celebrated. Currently, the Tadossauc/Richelieu nine is 74th on Canada’s Top 100 Public Golf Courses; even if it was remotely close to what Ben Cowan-Dewar’s grandfather remembered, it would vault up the rankings considerably.

Is it too crazy to think top 25 is in the cards? At one point, Manoir Richelieu was considered among the Top 100 Golf Courses in the World by Golf Illustrated. It might make a top 100 prettiest list now, but that is not at the hand of Huxham; the site itself is that awe-inspiring. With the addition of the two Cabot courses, Sagebrush, and Blackhawk, plus the usual suspects of the Thompson Five and the Colt two, it is crowded at the top in this country. However, even half of the architectural merit of any of those would vault it up the list. To think Top 25 is a potential reality is an insane hypothetical if you have seen the current course, but it has that potential.

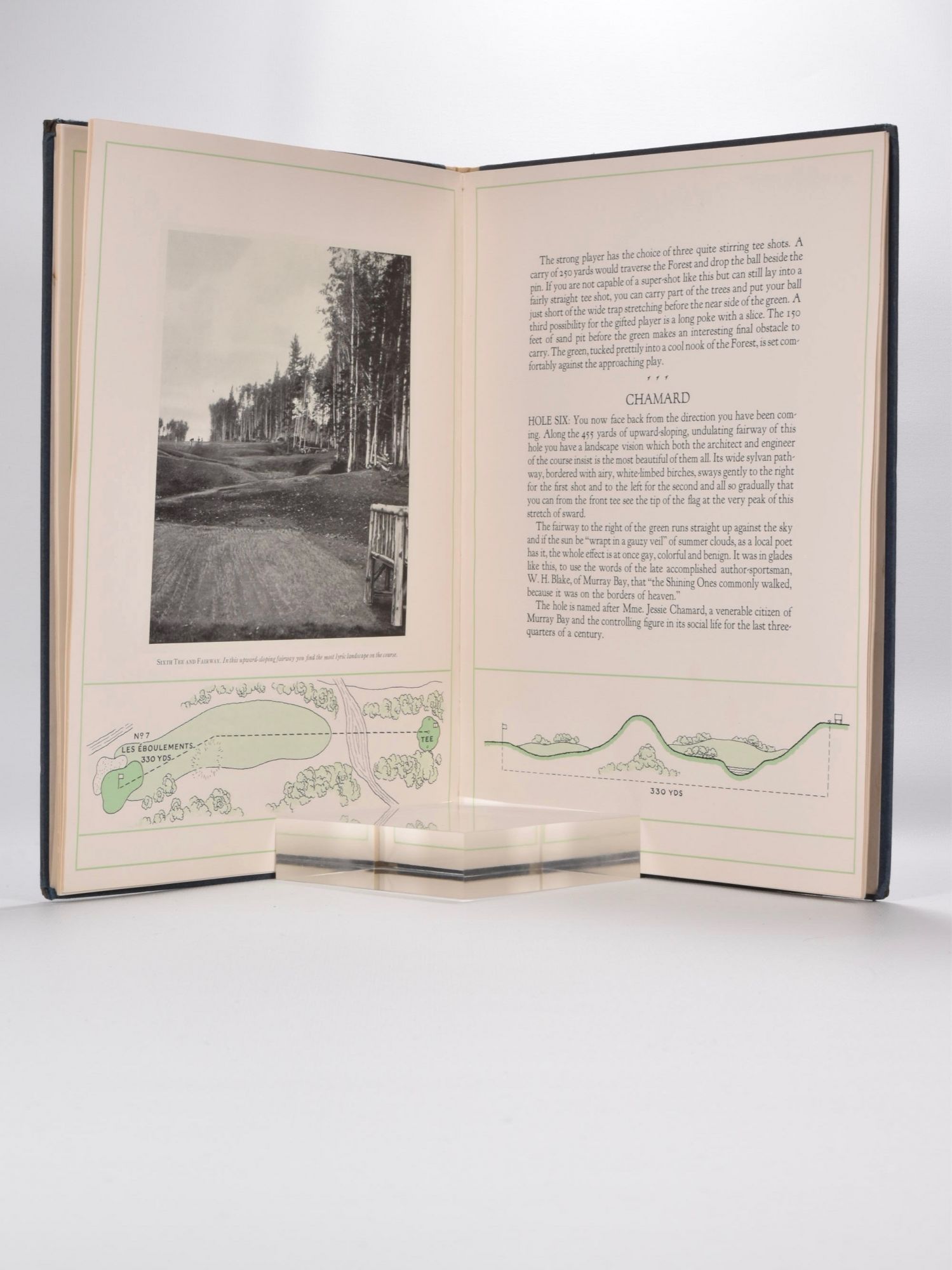

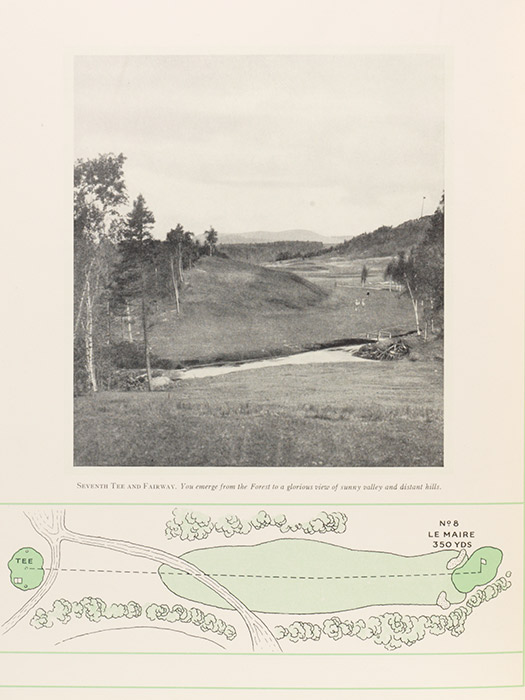

Perhaps most confusing about Huxham’s work is the surplus of information available about the original course. In all my research, it is among the most documented, photographed, and detailed of the Golden Age courses. Largely, this is because of Golf In The World’s Oldest Mountains, published in 1926 and written by Thomas Uzzell. With only one edition, the book is considered among the most rare in the world of golf. A price estimate suggests it is worth $300-$500 USD depending on its condition; on eBay, I have seen it being auctioned for 3500 euros (and sold). Nevertheless, it provides a detailed hole-by-hole drawing of each Herbert Strong hole, as well as images from each hole. If he intended to keep the original golf course’s character, he really didn’t do his due diligence and research. I used this book to put together a very low-effort master plan (below); if I can do it, I’m sure he could have, too.

There is no denying the challenges and hurdles with a restoration, and especially at Manoir Richelieu, where the resort is successful, and the golf course seems to do well with the clientele it attracts. Aside from that, parts of the golf course likely would not work. For instance, the new clubhouse is located near the 1st on the St. Laurent on the other side of the property, and restoring the par 3, 1st is likely not in the cards. Neither is the sharp dogleg right 5th on the original routing, which would go directly through the irrigation pond and some nearby homes.

One of the big thrills of life is a game of golf on a sporty course with intricate, but perfectly conditioned greens; but the biggest thrill of all is playing such a course where the scenery is equal to the game. Such is the Manoir Richelieu Golf Course, open for play on all its eighteen holes for the first time at the beginning of the summer season of 1926. Breathless golf, breath-taking scenery! The links at Victoria, British Columbia has its spacious seascapes; the National Links of America, on Long Island, has its lovely vistas of rolling sand hills and sheltered water; Gleneagles, set among the moors and lochs of the Scottish Highlands, has its quaint, Oldworld beauty; but the new course at Murray Bay in Quebec province, Canada, has a scenic background more imposing than any of these. It is now known as one of the most beautiful links in the world Thomas Uzzell, editor, American Golfer

This is without accessing the reality that once greens are gone, there is no getting them back. A restoration of a green is only possible with images and scans to get them correct, but even still, the magic is gone once they are ripped up.

Herbert Strong actually renovated the golf course in 1929/1930 to remove the par 3, 1st, replacing it with a long one-shot hole near the 7th hole on the Richelieu nine now, and in between the 12th and 13th. Nonetheless, in the above plan, we transport the original par 3, 1st after the 4th on land where the first ~200 yards of the par 4, 5th used to be. With the original 5th missing, we transplant that to the 7th hole on Richelieu, using Strong’s original par 5, 12th drawing in Golf In The World’s Oldest Mountains, but keeping with his updated dogleg left version to make room for a par 4 in the spirit of the original 5th.

It is completely understandable to see 6,280 yards and gasp given how far the golf ball goes, but fear not: the current Richelieu/Tadossauc combo maxes out at 6,066 yards, although a par 71. Canada need not be scared of a par 69; Swinley Forest, 50th best golf course in the world, tops out at 6,431 yards, par 69. If it’s such a big deal, pick one of the long 4’s and convert it if you so choose.

The Manoir Richelieu boasts one of the finest courses in Canada.

The Canadian Golfer, April 1931

One potential issue is starting on the new 1st, a healthy distance from the range and clubhouse. However, if you were to play the Tadossauc/Richelieu nine, you would cart to the proposed 15th hole anyway, so having to do that means very little if the golfer has to traverse already. You might as well keep the St. Laurent nine, and if you ever got the back nine/St. Laurent combo, the 10th hole is close to the current 1st hole on the Richelieu. Logistically, very little changes.

This fine course in Murray Bay in the Province of Quebec, is the creation of Herbert Strong and this work reflects him at his very best.

Golf Illustrated, July 1933

There is naturally some quirk here. It is not without its own hurdles and issues. Not everything can or should come back, either. The 1st and 5th are left behind, and as Brad Klein pointed out, the greens were unplayable for today’s agronomy standards (something I believe wholeheartedly). It becomes important to restore Strong’s intent with wild and interesting green complexes. No one would be able to put back a Strong green anyway, but a Hanse or Whitman or Riley Johns would be able to build something to fit with the scale, style, and architecture.

Further, blind shots are a potential issue here, and something the public might criticize. For example, the proposed 6th, 8th, 11th, 18th all have blind spots. There are minor safety issues, particularly with 14/15 tee and the 1st hole coming down the hill and the 6th/7th junction. However, these issues are dealt with at other classic public golf courses. Jasper Park has blind shots on the 3rd, 8th, and 13th, and it is just fine. Lakeview’s par 4, 18th tee above the 17th green works fine even if someone—in theory—could hit you from the 2nd or from 17. There are some safety concerns at Clear Lake, Grand-Mére, and Wateron Lakes and they all rank in the top 50 public courses.

My point is quirk makes golf courses. It is what separates golf from NHL or NBA stadiums, and also helps identify golf courses. Manoir Richelieu’s setting is almost second to none (a real compliment in Canada), with a beautiful town and resort to match. Restoring a golf course that not only provides some interesting features, challenges, and unusual architectural moments would help elevate the golf course to the stupendous hotel’s level and bring the golf course back into the limelight of Canadian golf.

The golf course and resort is just about two hours past Québec City. Remote golf destinations can and does work—hello, Cabot, Bandon, Sand Valley. It is time Fairmont begins to take the prospect of a potential world-class selection of golf courses available seriously. If Manoir Richelieu is restored, Jasper Park tended to, Banff Springs bandaged up, Montebello restored, suddenly, the company inserts itself into the discussion for some of golf’s great golf operators. For now, the catalogue is a “what if”; a reminder that at one time, golf in Canada was not an afterthought against the United States, but a worthy compliment to our friends to the south, and a destination worth exploring. I hope Manoir Richelieu can return to its former glory at some point, I know I would be curious to see how it stacks up.