Our love for Grand-Mère has already been steadily chronicled on this site, here, here, and lastly here—and we hope to expose it to a number of new golfers when it will play host to our second event next fall. If all we are remembered for is bringing attention to this Albert Murray, Walter Travis, and C.H. Alison collaboration near Shawinigan, then we will have done plenty good service, in my taste. In fact, even before visiting, Andrew and I wondered if we had potentially unearthed Canada’s answer to Crystal Downs—for those who don’t know, Crystal Downs, tucked in its lonesome corner of Michigan, was virtually forgotten until Tom Doak again brought back the wider-golf-world’s attention to it in the mid-1980s through his writings and restoration work. And although Grand Mère may not be quite as good as Dr. Mackenzie’s effort in Frankfort, we nevertheless believe that it is on the very cusp of the elite in this country.

As evidenced by the impressive list of architects who have plied their trade upon it, Grand Mère was once among the most acclaimed and prestigious clubs not only in Quebec but in Canada. There still lingers a palpable sense of gentility to the club and its grounds: from the winding drive near which a few turn-of-the-century stone mansions are visible, to the sophisticated clubhouse and detached dining-room with their tasteful white paneling and elegant masonry, to the old world locker-room and lounge. A club that is very much “frozen in time” would be an apt way to describe it. As I remarked to Andrew, the whole area feels alot like a number of rural towns in western Pennsylvania or in upper New York, where remnants of a bygone, more prosperous era are similarly still visible all throughout them.

In truth, I’d always assumed its history to be rather straight-forward. At first, George Cahoon, an American executive of the nearby Laurentien Pulp Mill, hired Frederik de Peyster, a local landscaper, to lay out a few rudimentary holes, which opened in 1912 according to Patrimoine Shawinigan. A few years later, Albert Murray, Quebec’s leading architect of the time, added a few more holes to bring the total to nine. Then in 1917, Walter Travis, likely America’s most known practitioner in the early development of the sport on this continent, was summoned by Mr. Cahoon to transform Murray’s creation into something that could perhaps stand toe-to-toe with the country’s best. And, finally, C.H. Alison was charged with improving and expanding Travis’s creation to a full eighteen holes. In short, the trajectory of the club very much mirrored that of the prosperous mill and area in the first decades of the twentieth-century.

More or less, this is what happened, but my search still revealed a number of interesting details and a few questions, many of which still remain unanswered. Moreover, there is very little information available to the public regarding its history, so hopefully this serves that purpose, particularly for those planning to visit it in the coming years. What follows is not a complete historical survey, of course, and covers mainly its formative stage, from about 1910 to 1923. Since then, the club seems to have operated rather steadily and without fuss, only inadvertently returning to the national spotlight due to Jean Chretien’s scandal dubbed “Shawinigate” in the mid-1990s, where, it was claimed, he profited from a number of real-estate dealings in town, including his brief ownership of it.

What originally triggered my curiosity, and in turn caused me to dig deeper into its story, was an email from Ian Murray. Ian, whose back and forths I deeply cherish, is one of the preeminent chroniclers and preservers of the early development of golf in Canada, especially in regards to the highly important roles his grandfather, Albert, and great-uncle, Charlie, both had in it—in truth, the popular annals of our history have been far too thin and unjust towards them, I believe. I do not think it is too big of an exaggeration to claim that Albert, in particular, was very much Canada’s version of “Old” Tom Morris, as a player, architect, teacher, writer, and innovator. For those interested, I especially recommend, among other things, Ian’s story “The Stone Cutter and the Golfers”, which was recently published by the Stanley Thompson Society in one of their editions.

Out of the blue, Ian, knowing our love for Grand Mère, directed us towards a clipping he’d found in an edition of the Montreal Star from June 1915; in it, it is reported that “after careful inspection Willie Dunn gave his opinion that the course could not be improved upon, that Murray had utilized every possible piece of ground, and placed the holes in very picturesque places.” Furthermore, the article suggests that Dunn proposed another nine holes, which would be added “without any alteration to the present nine.” This sent my alarm bells ringing: why would the club dismantle what was seemingly a good nine holes built by Albert Murray to make way for Travis’ work, especially considering that there already seemed to be an appetite for eighteen holes as far back as 1915? This didn’t seem to make a ton of sense. As one of the foremost pioneers of the practice in North America, Dunn’s voice would carry credibility, I presumed.

Of course, as with any query regarding this formative era of Canadian golf, I searched the archives of the Canadian Golfer in which mentions of the club are rather and surprisingly scarce considering its pedigree. The first notable mention of Grand Mère occurs in the October 1915 edition, where the author claims that “that the club had spent 12000$ to improve the links, that the greens are especially good, and that the ravine holes provide shots equal to any in Canada.” This seems to corroborate with Dunn’s impression of Murray’s effort. Yet, two years later, in the November 1917 edition, it states that “Walter Travis came to Grand Mère with the purpose of laying out a “permanent course”, which was to be 3100 yards in length, and that he also played a match vs the club’s professional.” Surely, I wondered, spending $12,000 on its construction, as was claimed back in the 1915 edition, would be enough to consider the course “permanent”, nevermind Dunn’s glowing account of it. With this, confusion truly set in. In a later exchange, as I related my conundrum to Ian, he assured me that he had also come upon similar instances of conflicting and inaccurate reporting in the Canadian Golfer.

Still, I continued searching edition by edition, year by year, to find references to the club in its pages. Until 1920 mentions of it remained scarce and rather in passing—a retrospective claim in the February 1919 edition of the Red-Cross match Travis had played in 1917 and of his proposal to expand the course to 3100 yards; another in the June 1920 edition stating that the club had “one of the best courses in Quebec”. In the July 1920 edition, there is a mention of the first amateur to have made a hole-in-one at Grand Mère, on the 130 yard par 3, 18th. Once again, I figured that they simply played Travis’ nine hole loop twice, and that this golfer happened to have made his ace on the back 9.

1921, however, would prove to be the club’s most noteworthy season. As early as April, the Canadian Golfer began advertising a multi-stop exhibition tour featuring George Duncan and Abe Mitchell which was scheduled for late summer. The tour was set up by a Mr. Hollander from New York and 5 matches were planned: at Scarboro, Brantford, Lambton, the Country Club of Montreal, and lastly Grand Mère on August 28th. The price charged per match was $500, and the article mentions that Mitchell and Duncan had no desire to play in Western Canada, despite a number of clubs expressing interest in hosting them.

Exhibition tours such as these, featuring the top professionals from the United Kingdom, were quite common in this period. Ted Ray and Harry Vardon, for example, had undertaken a strenuous 91 date circuit the year prior, capped off by Ray’s victory and Vardon’s joint-runner-up finish at the U.S. Open at Inverness. George Duncan, of Methlick, Scotland, had recently won the 1920 Open Championship at Royal Cinque Ports, and Abe Mitchell, who is now probably best known for being the model golfer on top of the Ryder Cup trophy, was widely considered to be the best golfer not to have won it in this period. So, suffice to say, this would have been quite the draw, especially for a rural, isolated community such as Shawinigan. In fact, Mitchell is a rather fascinating, albeit largely forgotten figure.

1921 is also the year when Alison provided a set of blueprints to expand the course to eighteen holes. Or was it already eighteen holes? Herein lied my curiosity, because, for no real reason, I was dubious that Duncan and Mitchell would travel all the way up to Shawinigan to play the same nine holes four times over in a single day – nevermind that all of the other courses on the rota were eighteen holes. Again, perhaps they may have been perfectly (read: economically) willing to, but I wanted to delve deeper into it. Surprisingly, Alison’s visit (if he did in fact visit the site in person) is not mentioned in Canadian Golfer, nor is it reported that he provided plans to expand the course. Yet his work at York Downs, in Toronto, is closely monitored and reported on a few times.

Although Duncan’s game, in particular, was reported to be in bad shape all summer, he still managed to place a respectable 5th at that year’s Open Championship at St Andrews; meanwhile, Abe Mitchell, who was in top form despite at a poor showing at The Open, secured an important and lucrative victory at McVitie and Price Tournament played at Oxhley Golf Club. A month later, the July edition of the Canadian Golfer decrees that it will be “entirely” up to the respective clubs to decide their opponents, as well as the referees for the match. Despite what had been reported in April, this edition also reports that the pair had been scheduled to play an additional three matches in Winnipeg, and that they had recently arrived in New York in order to prepare for the “U.S Championship”.

The next month’s edition remarks that they had played in a series of exhibition matches against the likes of Jim Barnes, Tom Kerrigan, and “Jock” Hutchinson at various clubs throughout the northeastern United States, and that they had been drawing large galleries. This page -long article also indicates that C.R. Murray, the professional champion of Quebec, and David Cuthbert, the club’s head pro, would be their opponents at Grand Mère.

The pair would eventually make a clean sweep of Canada, a feat announced in bold lettering by the Canadian Golfer. At Grand Mère, Duncan finished with a 36 hole total of 141, while Mitchell shot an afternoon 69 to redeem a lackluster morning round of 75. The pair vanquished their opponents easily, and afterwards Duncan laid tremendous praise upon the course: “I can’t really express how much I liked your course here, but it was a joy to play over it. It compares favourably with any course I’ve seen on this continent, including some of the so-called “millionaire courses” in the United States. You must make your six holes to keep the same high standard. What I liked particularly were your greens: they are real greens, not excelled, in my opinion, on this side”. Wait a minute, I thought, adding six more holes? Surely they hadn’t had time to add three more holes since Alison’s visit (or at least when his blueprints are dated) merely a month prior to the match. There seemed to be something missing between the 3100 yard course that Travis had reportedly advised them to build back in 1917 and the one that had hosted this match in August of 1921. I attempted to inspect the hole-by-hole scores (though without the pars and yardages) provided in the Canadian Golfer, and they seemed to indicate enough of a variance to presume that the same nine hole loop hadn’t been played four times—but, of course, this was a small and insufficient sample from which to safely deduce that there were more than nine holes.

As is common to such historical searches, I proceeded to hit an impasse for a few weeks, finding and being directed to a number of interesting clippings and briefs, but nothing that really shed fresh light on the course and its different configurations. Yet faith, once again bearing the humanoid figure of Ian Murray, reappeared in my inbox with an article from Montreal Star in which a hole-by-hole tour of the course is provided. In short, Ian had found the missing piece to my search. Published in the July of 1922 in the section entitled “Golfing Notes from Near and Far”, the unnamed author remarks that “to complete the eighteen the first five and ninth are played over again”. With this twelve hole-loop in mind, I returned to the scorecards from the 1921 match and, sure enough, this configuration matched up nearly perfectly to their cards—for example, on the 13th hole of the match, a repeat play of the par 5, 1st, the scores match up to what you would expect on a par 5, and so on.

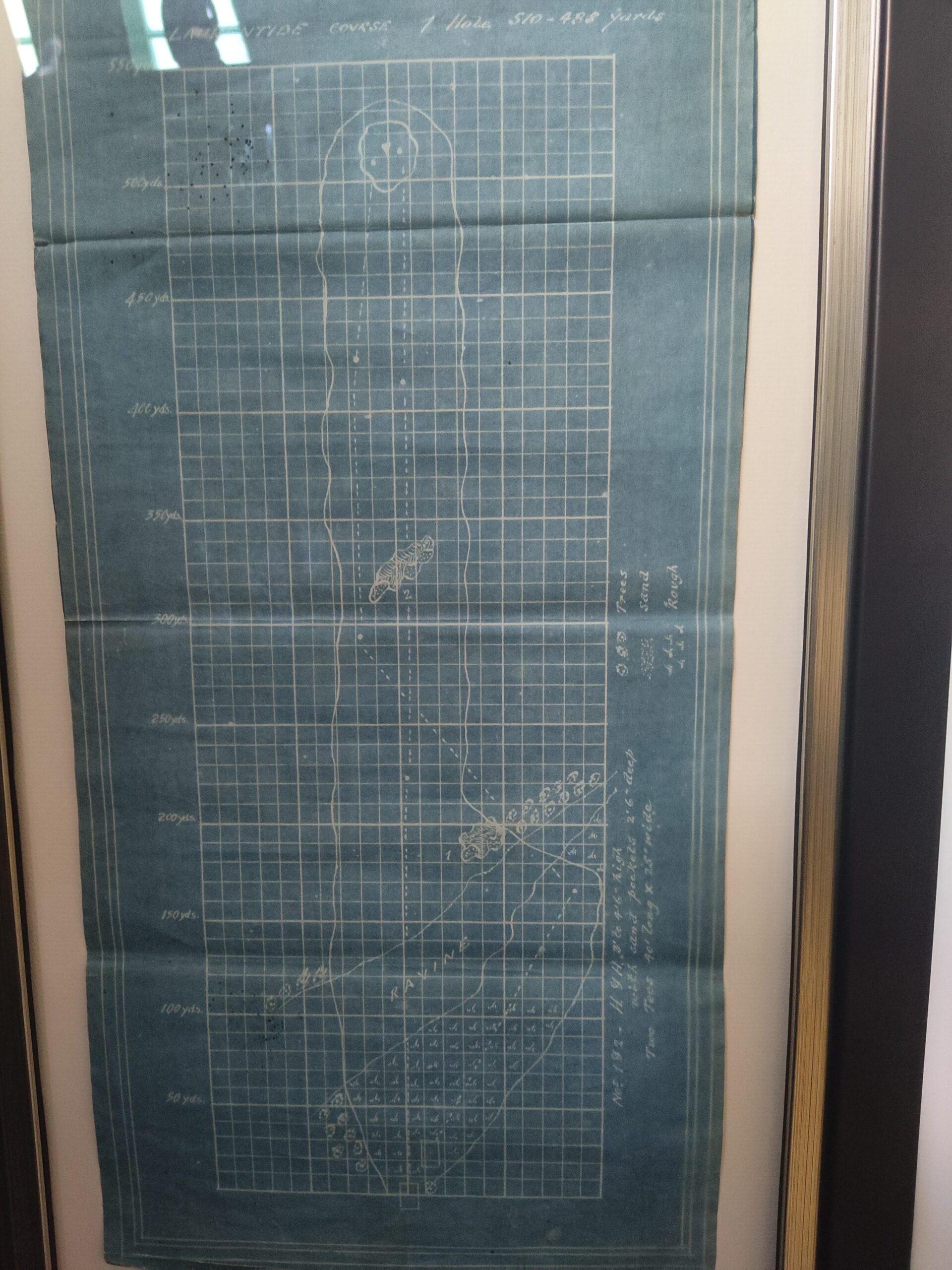

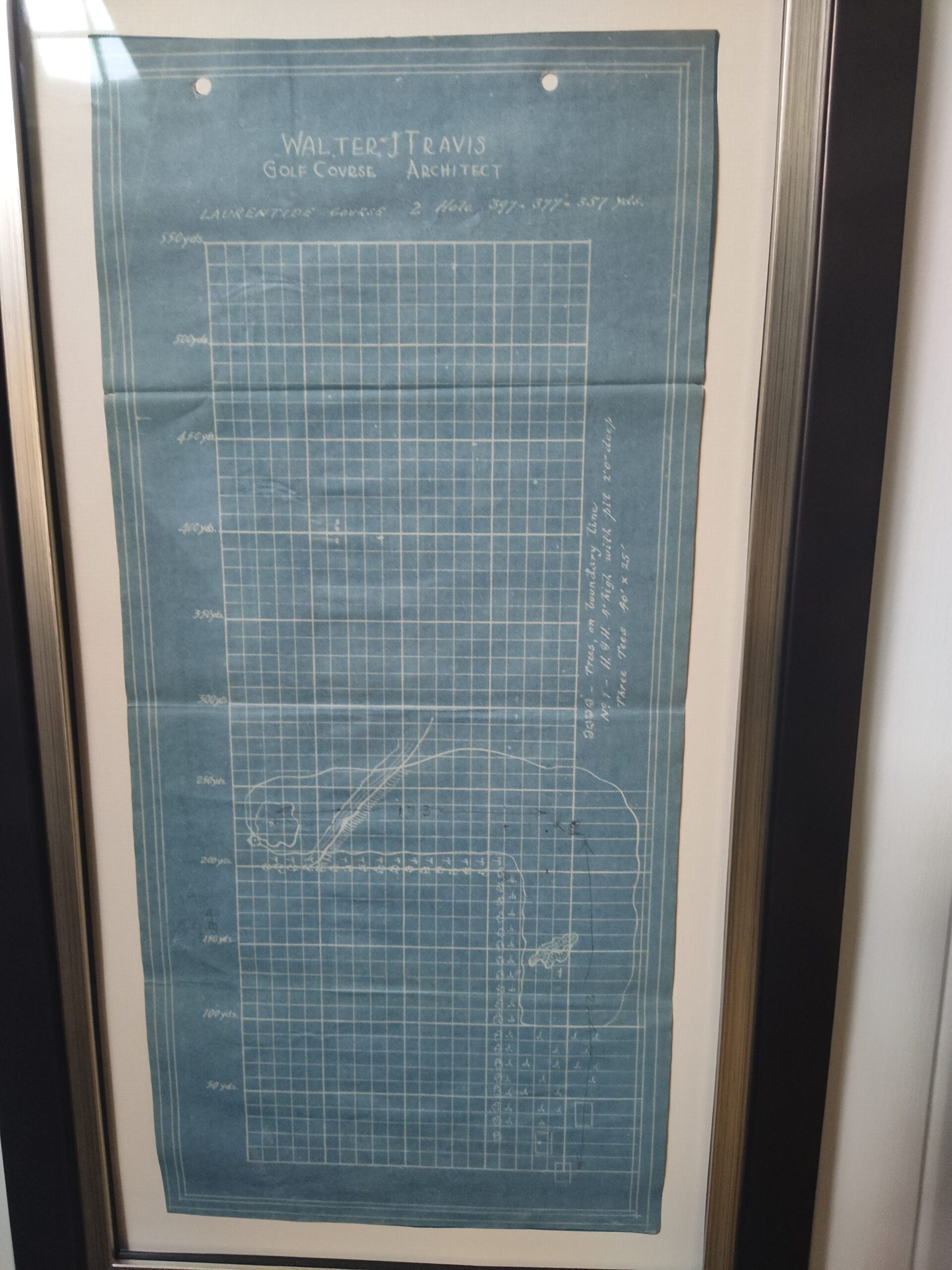

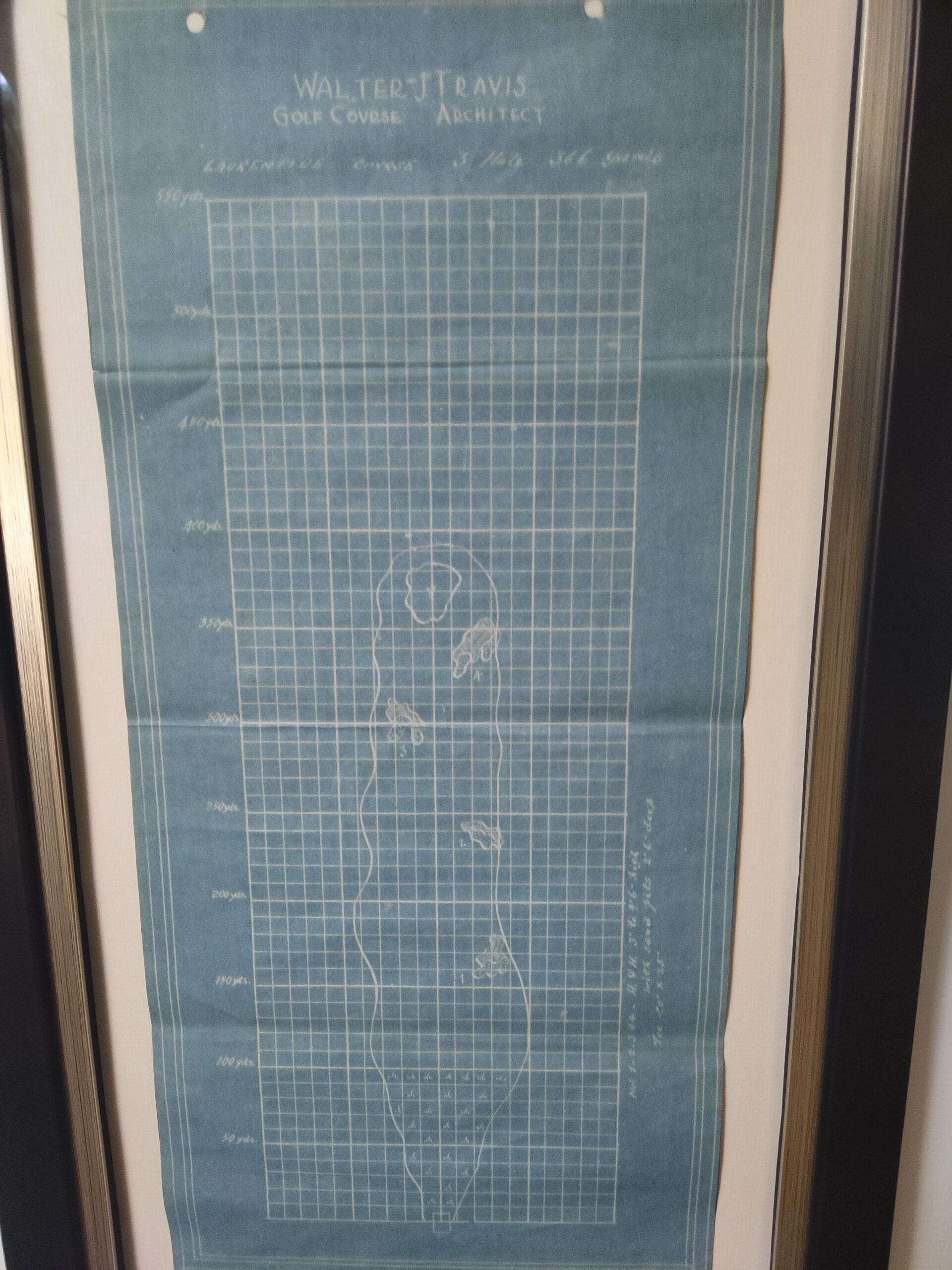

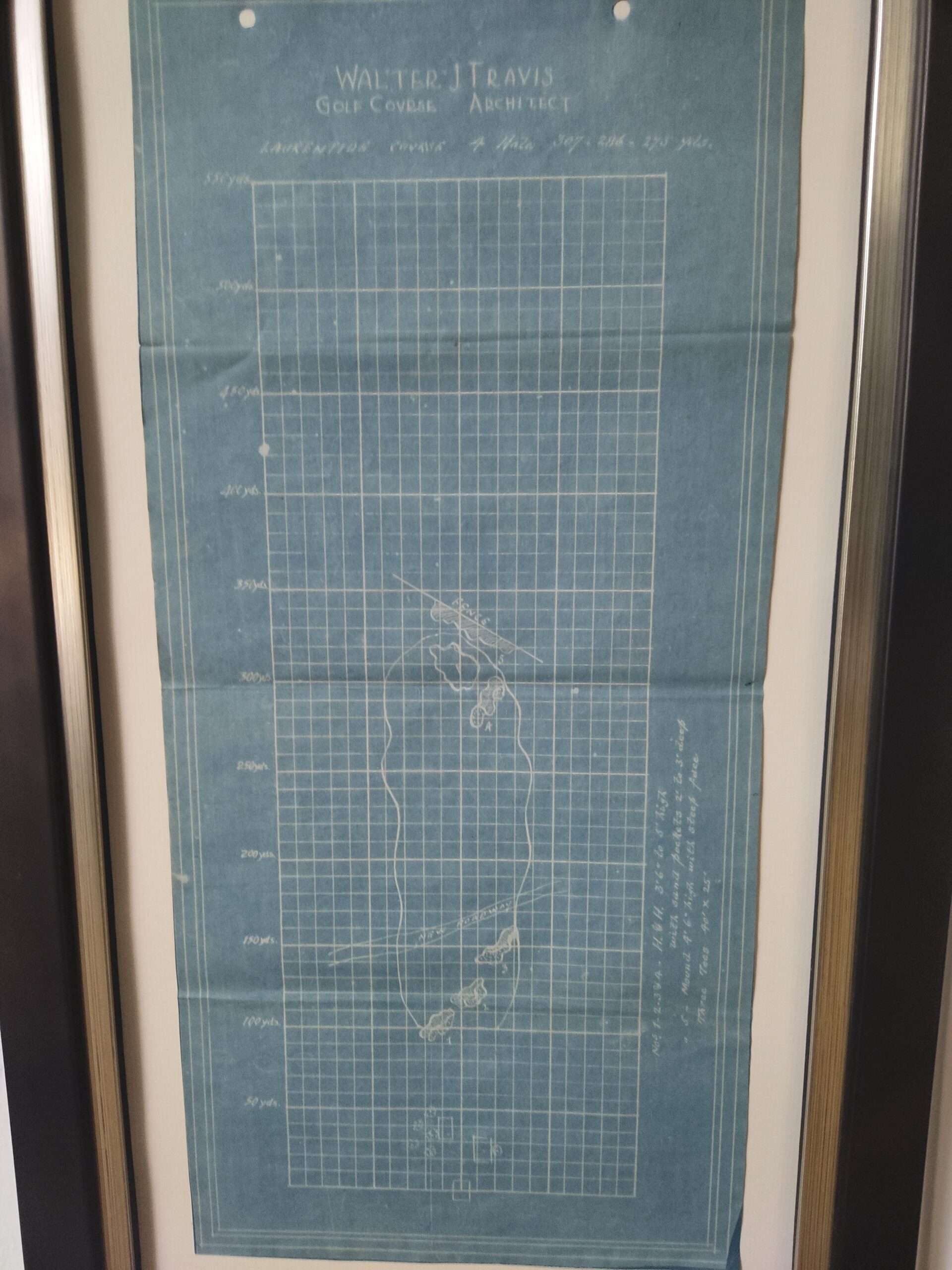

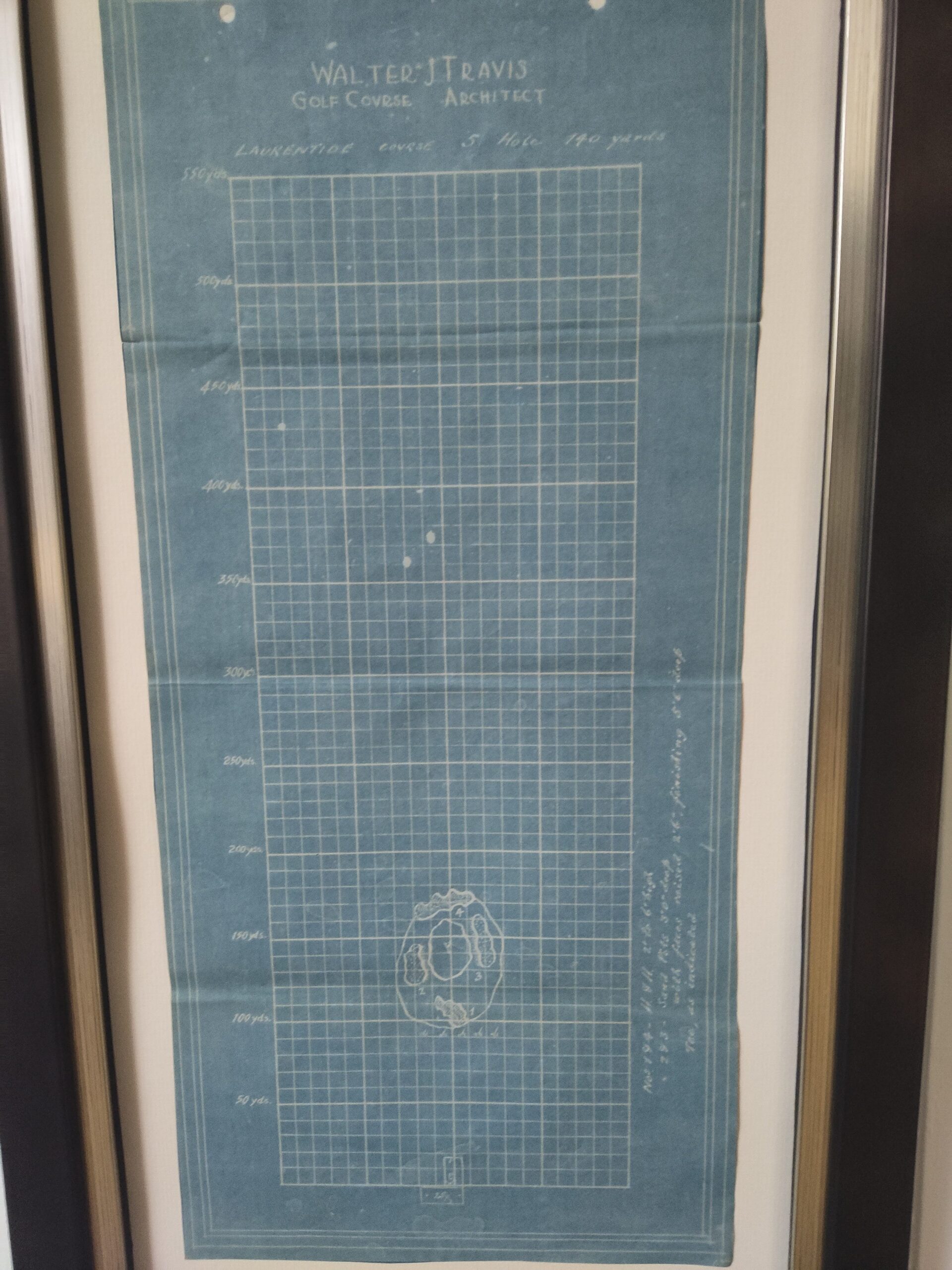

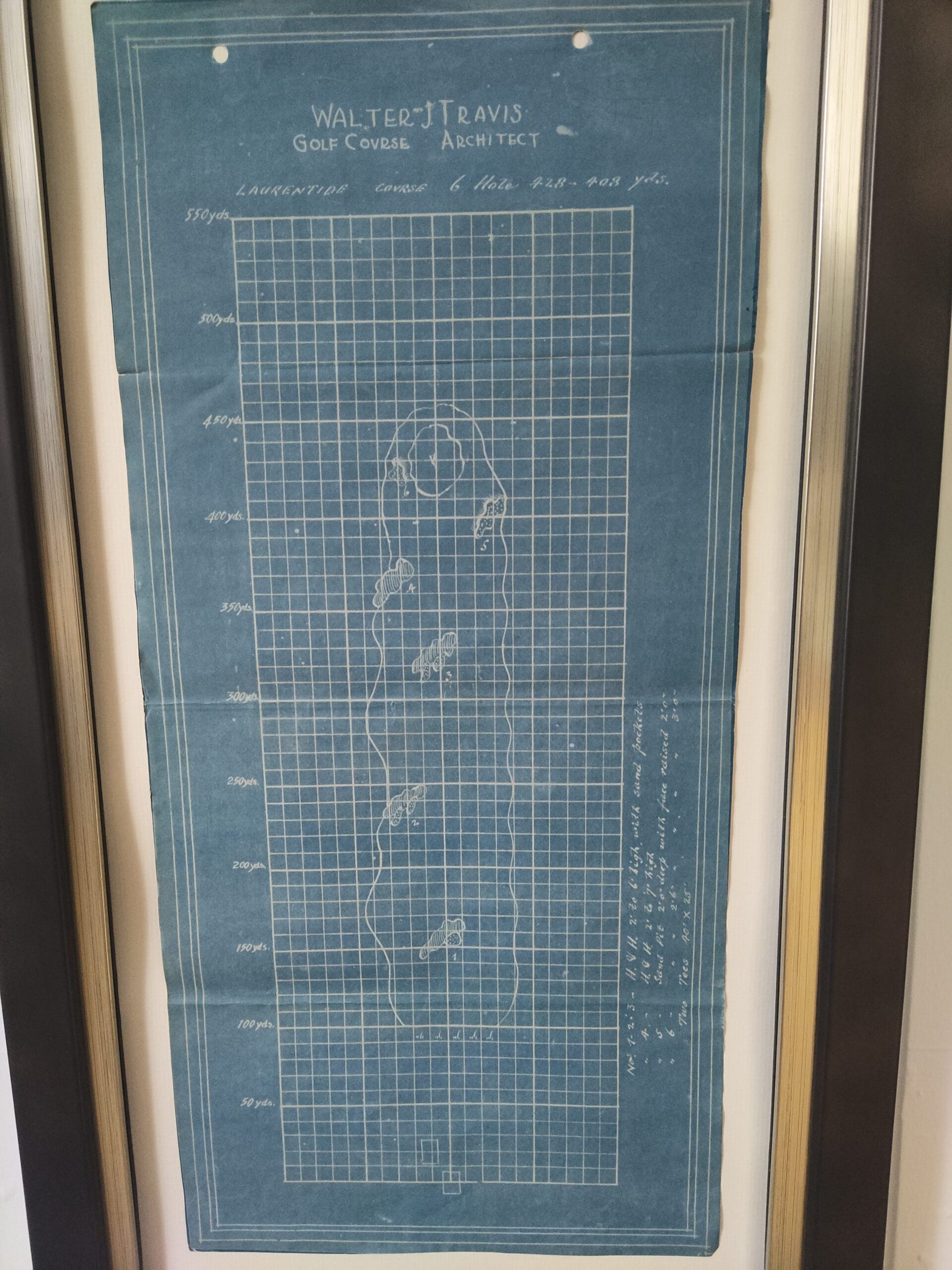

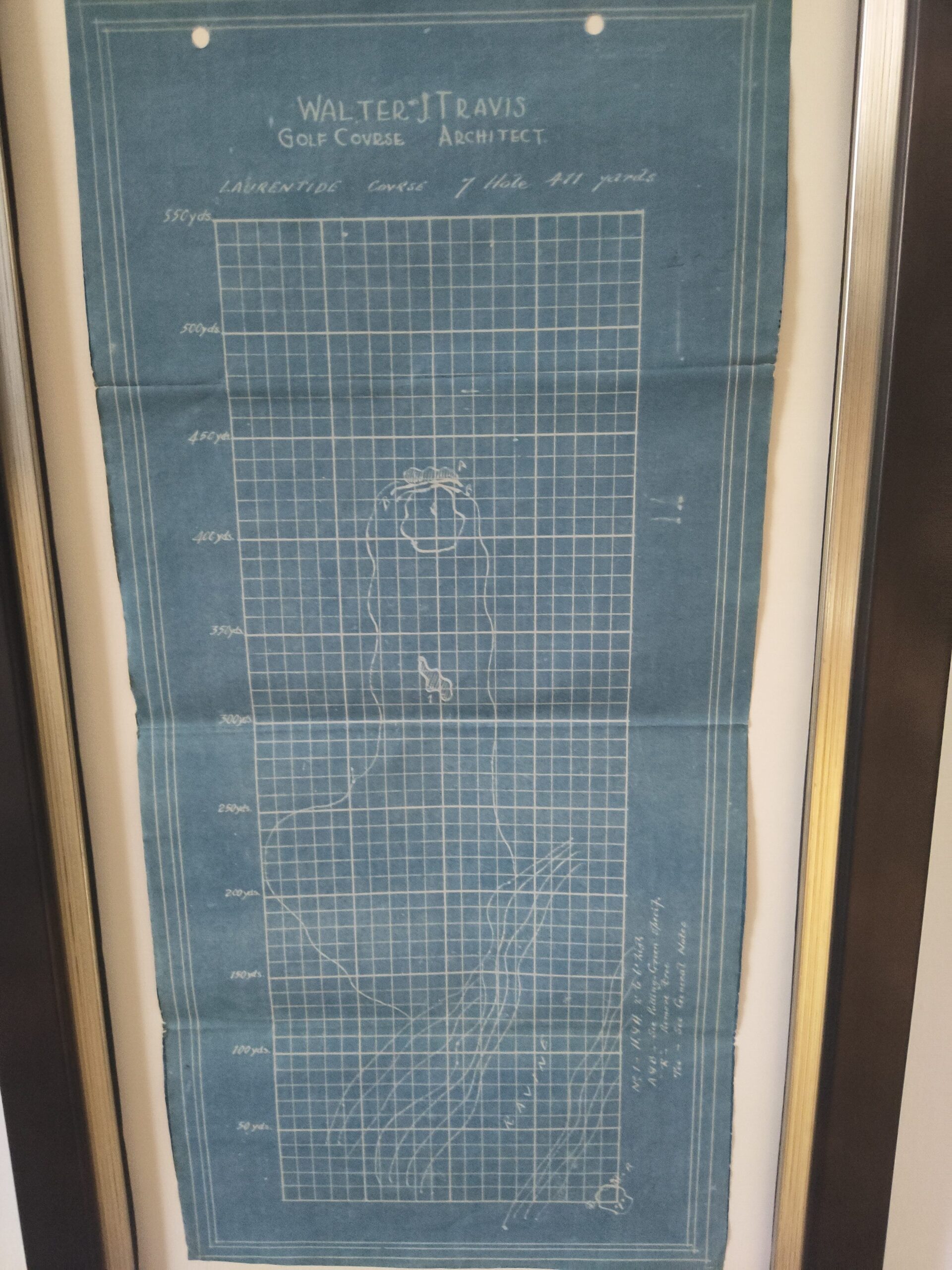

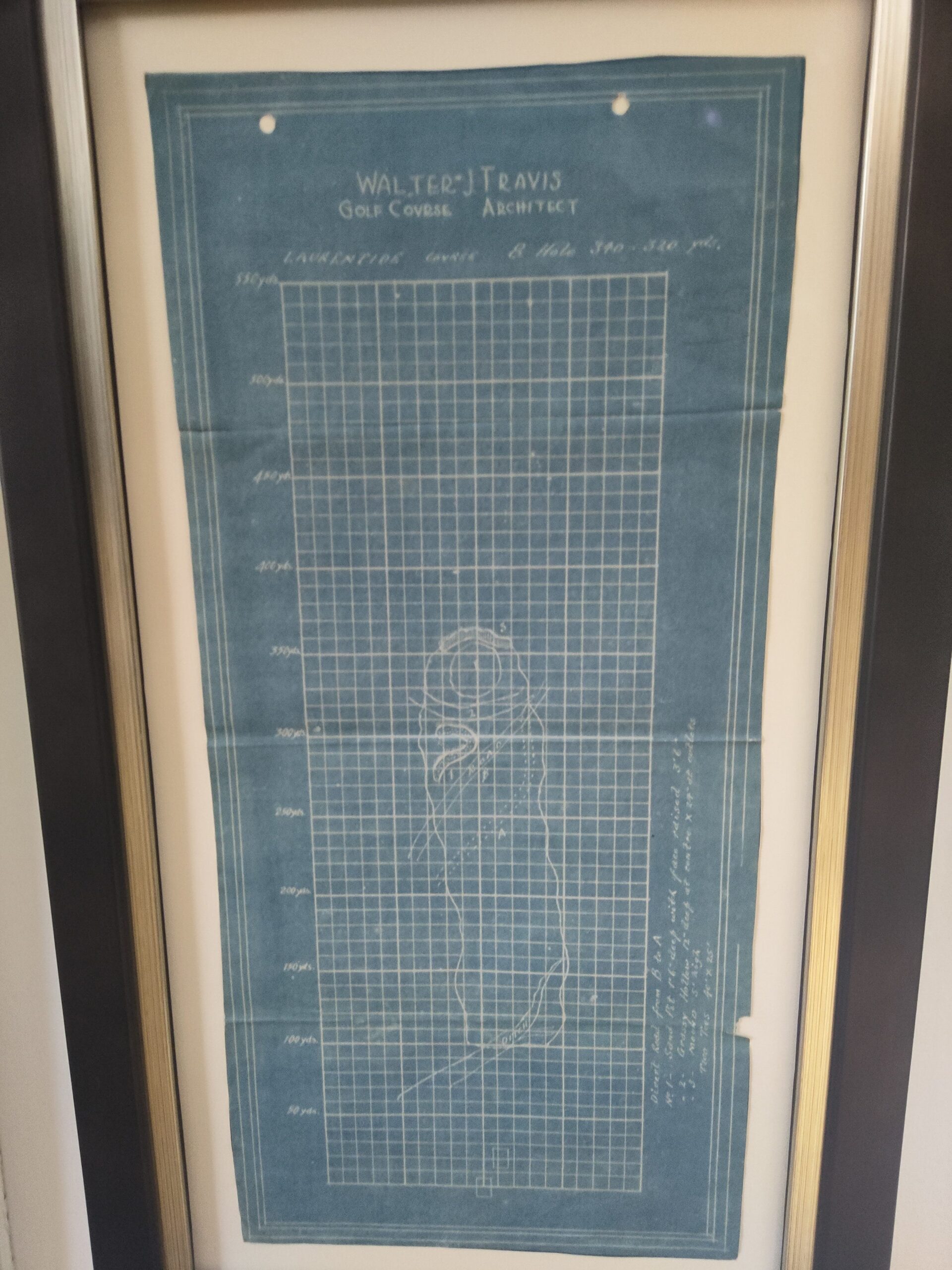

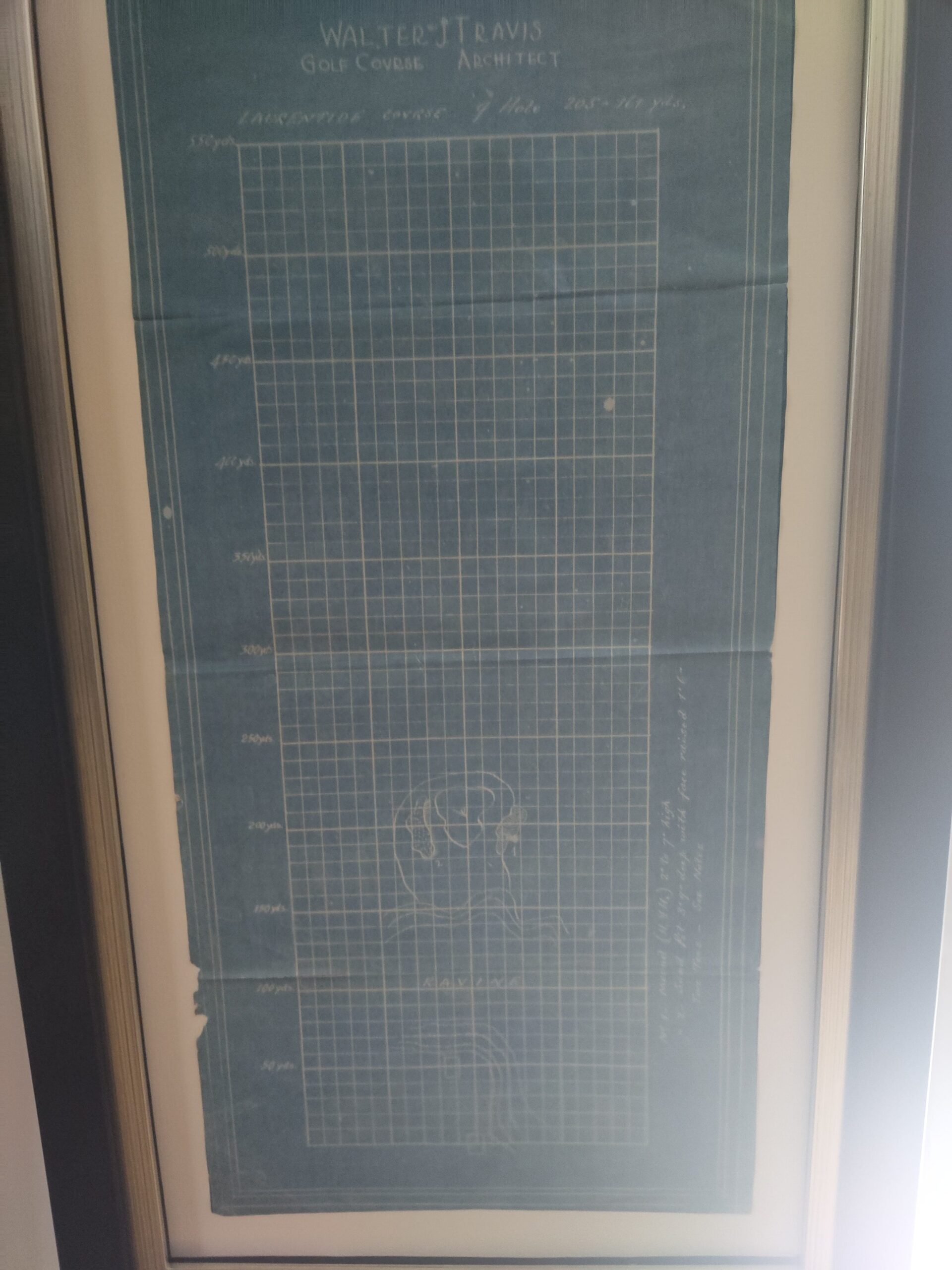

Evaluating the author’s descriptions of the first five holes, they seem to be, more or less, unchanged from how they presently are. Furthermore, the club is in possession of Travis’ blueprints for the project, and Richard Rousseau, the current owner, was kind enough to let me peruse them during a mid-winter visit I took.

Fighting the cold and an early morning drive through Montreal, I met Jim Buki, a long time member and stewart of the game in Quebec. Mr. Buki had found Travis’ blueprints for the course while cleaning his father’s bookshelves. His father served as the club’s greenskeeper from 1947 to 1983. In fact, prior to Mr. Buki’s discovery, Travis’ involvement with the club had been essentially forgotten.

A set of remarkable artifacts, we find among them Travis’ renderings for what would be the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th holes according to the 1922 configuration of the routing (and still today’s, minus the brilliant par 3, 12th, which returned to the clubhouse and thus had to be eliminated by Alison in order to expand the routing to 18 holes).

(All of Travis’ blueprints are available in the slideshow at the end of the article)

After all, twelve hole routings were fairly common in this era. What is missing from the blueprints, however, are the 6th, 7th, and 8th holes. In the description of the 6th hole, a leftward sweeping dogleg to a green perched upon a shelf, the author of the article in the Montreal Star directs us to Duncan’s claim that he had “never seen a better golf hole than this one; it’s a wonder.” In a brief though confusing addendum to the piece, the author also remarks that the “new sixth hole will be better than the present ones (sic).” Does he mean that the new sixth hole (i.e. after Alison’s improvements are done) will be better than the present one (i.e., the one described by Duncan as the best he’d played)? Or does he mean that the six new holes to be built according to Alison’s plan will be better than the present ones? Inspired by Duncan’s praise after visiting in 1921, I am more willing to inscribe the editorial fault to the ultimate word in the sentence, since the author also states the 7th is “another new hole”. My fairly confident hunch is that, following the match which occurred a month or so after Alison dated his plans (June 1921), the club had begun to put his vision into practice, and these three holes were where they began to do so. This begs the obvious question as to who built them, since we have no proof of Travis having worked on them.

Well, I guess somewhat obviously, Albert Murray seems to be the man to credit. Were these the holes, then, that Dunn viewed when he gushed about the superlative quality of the course in 1915, before Travis had arrived? Of course, we’ll never know for sure, but what cannot be denied is their quality, for even today, they are remarkable and among the better ones in the layout. And, according to the description given of the 6th in 1922, at least, Alison seems not to have altered it too greatly from its original form.

Working backwards from this point, being confident in my conclusion that the 1921/1922 configuration of the course had been composed of nine holes by Travis and three by Albert Murray, I began trying to piece together what had been Murray’s original nine holes (i.e. the configuration of the course that Travis had played in 1917?). Here you may pause and wonder why I wanted to pursue such an exercise to this extreme, why I wanted to bog myself down in such seemingly minute details. Aside from the fact that very little information is publicly available regarding Grand Mère’s history, coupled with my steadfast belief that a course of its architectural pedigree merits such careful attention regarding its development, there is a kind of historical malaise, or negligence, or clumsiness, that has dogged and, I believe, greatly harmed the development of golf architecture in our country. And this, I have suggested elsewhere, especially manifests itself in the deplorable architectural state in which so many of the historical golf courses currently find themselves—the wave of restoration and renovation that has crashed into the American shore with the strength of a tsunami but has so far arrived on ours merely as a gentle, lapping one. In other words, Michael Flannery’s frustration that Scottish golf historians “doggedly continued marching to their own drum – oblivious to the conclusions of contemporary research -” and were “shackled by a lamentable lack of academic curiosity and enveloped in a fog of dogma, vested interest and torpor” is very much applicable to Canada, too.

Perusing Google Earth, noticing what appeared to be the remnants of two golf holes in the trees behind the current 2nd green and 3rd tee, I thought I had solved the puzzle. The pieces seemed to fit perfectly: these were two holes that had originally been built by Albert Murray and abandoned during the application of Travis’ plan. Upon including them into my reconstructed layout, they formed a seamless nine holes of golf (current 1st, 2nd, abandoned 3rd, 4th, current 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th). And, furthermore, using Google’s measuring tool, the total yardage of this configuration came close to the reported 2600 yard length. However, my theory was debunked by Mr. Buki, who informed me that these two corridors had in fact been golf holes at one time, but that they’d been built in the 1970s, when some members had hoped to convert the current 3rd and 4th holes into a driving range. Feeling grateful that this catastrophic plan had failed to materialize, but also somewhat disappointed that my theory had been debunked, I continued on searching.

Still, the exact configuration of Murray’s original layout remains somewhat of a mystery. But Mr. Buki also directed me towards an interesting discovery made by Anthony Gholz, whose wonderful book, Colt and Alison in North America, had of course originally brought our attention to Grand Mère. Mr. Gholz, being the preeminent expert on C.H. Alison, discovered clippings in two Vermont newspapers regarding Lynn Edward Lavis’ employment at the Laurentide Pulp Mill. By 1924, two years after Alison dated his blueprints for Grand Mère, Mr. Lavis was in charge of the construction of Timber Point, Alison’s biggest project at the time. The clipping taken from the September 3rd edition of the Burlington Daily News states that “Mr. Lavis is a graduate of Syracuse University and now holds a responsible position with the Laurentide company, ltd, of Grand Mère.” As Mr. Gholz deduced in his correspondence to Mr. Buki, with Mr. Lavis presumably working as a landscape architect for the Pulp, it would be a natural progression for the company to ask him for revisions regarding their golf course, especially since we know that by late 1922, a full year after Alison’s visit, there were still three holes left to be built; a brief note in the October 1922 edition of the Canadian Golfer relates Jim Cuthbert’s (the head pro at the time) sentiment that they had had “wonderfully successful season” and, in turn, started to “build three more new holes which will greatly improve our already fine golf course”. It seems likely, though it remains unconfirmed, that Alison and Lavis met and formed their partnership while working at Grand Mère – a neat piece of golf history borne here.

Yet, as the century progressed, the tide of societal and economic forces that decreed communities such as Shawinigan its original victors soon shifted and the rapidly changing world began to relegate them to the periphery of its focus. Luckily, the golf course, itself, bears surprisingly few of the marks and scars left by the hands of chance and change that are visible in the largely dilapidated and depressed community all around it. I asked Mr. Buki why he believed that Grand Mère had remained in such good architectural shape, especially in comparison to so many of the other historically important golf courses in the province which have been marred by poor renovations, negligence, and overgrowth, and he credited the care and knowledge of the club’s custodians. He related just how forcefully his father, especially, loved the place, and how he rarely spent a day away from it.

And herein lies perhaps the most surprising and pleasant aspect about the club: that it has essentially been left as Alison intended it to be when he provided the plans in June of 1921.

I’d like to thank Andrew Harvie, Ian Murray, Jim Buki, Alain Chaput, Anthony Gholz, and the Rousseau Family for helping me with this article and with my search; without them merely of sliver of it would have been possible. In truth, my role was mainly that of a curator, taking advantage of their fine work and putting it together as a package.

- Walter Travis’ 1st hole

- Walter Travis’ 2nd hole

- Walter Travis’ 3rd hole

- Walter Travis’ 4th hole

- Walter Travis’ 5th hole

- Walter Travis’ 6th hole, now the 9th

- Walter Travis’ 7th hole, now the 10th

- Walter Travis’ 8th hole, where the current 11th is

- Walter Travis’ 9th hole, which utilizes the current 18th green

Leave A Comment