Feature Interview with Michael Moore

May, 2017

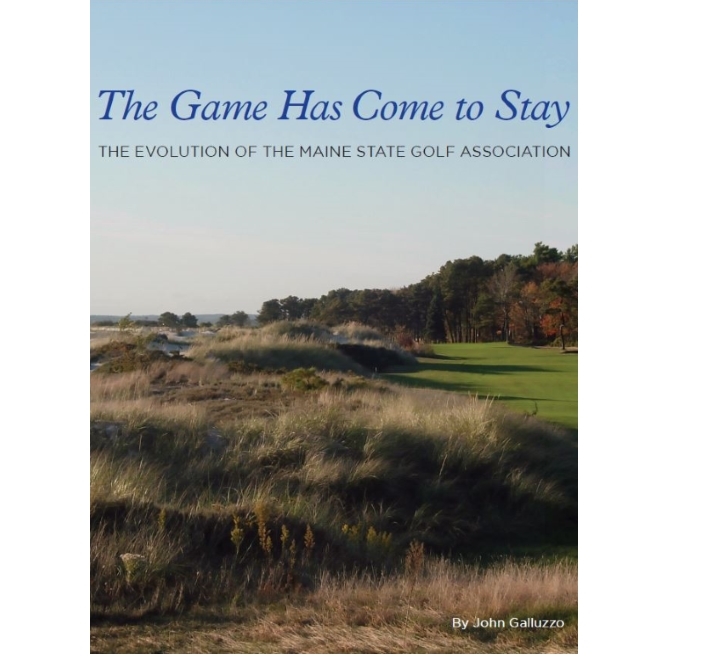

Michael Moore started playing golf in 1974 at Mount Douglas Golf Course in Victoria, British Columbia under the tutelage of his grandfather, Rear Admiral Patrick Budge. He has served on the Maine State Golf Association board since 2013 and is currently the secretary. He is a member at Riverside Municipal Golf Course (North) in Portland, Maine, a Wayne Stiles design from 1932. He has qualified for five Maine Amateur Championships and his favorite golf course is Eastward Ho! in Chatham, Massachussetts. A web developer by day, he moonlights as a visual designer (www.greenlightspecial.com) with an emphasis on the golf industry. His latest creative endeavor was to gather and edit the photos for The Game Has Come to Stay, the MSGA centennial book written by John Galluzzo, which was published this month and can be purchased at www.mesga.org/book.

How did the book The Game has Come to Stay come about? What proved to be some of the best sources for photographs and artifacts?

This project was directly influenced by the Massachusetts Golf Association’s excellent centennial book A Commonwealth of Golfers. I give full marks to our executive director Nancy Storey, who proposed the idea of a similar work and refused to take no for an answer.

I love the photos in this book. My friend David Cummings gave us access to his enormous collection of books, postcards and memorabilia, and GolfClubAtlas participant Brad Tufts contributed some badly needed photos of golf in Aroostook County. Mark Laney from Augusta pitched in with some new research into the early days of Maine golf. Historical societies had the best photos for the least effort. Portland Country Club had boxes and boxes of stuff. I learned to ask and to keep asking. There was so much left unpublished and undiscovered that I became very interested in creating a statewide archive.

What do you hope it will accomplish?

First and foremost, this is a gift to the clubs that comprise our membership. In the book, you see that in the early days clubs are dropping in and out and asking “what have you done for me lately?” The MSGA is constantly asking itself the same question. This book is a small token, but I think that over time our member clubs will appreciate being memorialized in this fashion.

I hardly ever make predictions, but it seems obvious that Top Golf is going to make significant inroads and change what it means to play the game. As someone who has railed against golf carts (whose emphasis on sitting and drinking alcohol laid the groundwork for these emerging variants) in every possible forum, played with persimmon gear well into this century, and edited this loving remembrance of things past, I’m at peace with that. When the 200th anniversary book is written, this one will be seen as a compendium of men and women wearing ludicrous clothing, or a vital resource that helped preserve courses from 1916, or something in between.

I love President George HW Bush’s quote in the forward letter: “Golf in Maine is just different than in other parts of the country. Of course, playing in Maine, you experience all four seasons—sometimes in the same round. But it’s more than the elements. It’s more than the timeless course designs. Today, more than ever, I realize it’s the people—the Mainers themselves. They have brightened my time on the golf course, and just plain life for the Bush family, in more ways than mere tongue can tell.” Can you expound on that?

I love President George HW Bush’s quote in the forward letter: “Golf in Maine is just different than in other parts of the country. Of course, playing in Maine, you experience all four seasons—sometimes in the same round. But it’s more than the elements. It’s more than the timeless course designs. Today, more than ever, I realize it’s the people—the Mainers themselves. They have brightened my time on the golf course, and just plain life for the Bush family, in more ways than mere tongue can tell.” Can you expound on that?

I can’t really answer this, so let’s throw it over to Mike Sweeney, to whom I will always be grateful for reinvigorating my interest in Maine golf. One day I casually mentioned that we should take a boat ride to North Haven and Tarratine. He didn’t let it go, and that trip was unforgettable. He has taken me all over the state, and he writes:

Simply put, playing golf in Maine is the easiest way for me to play golf in Europe without getting on a plane. The names alone are worth the trip: Nonesuch River, Mingo Springs, Grindstone Neck, Great Chebeague, and the list goes on. Maine golfers share the same warmth and dedication to simplicity that you consistently find in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Carts can be found in certain places, but it a push, pull, or carry your clubs kind of place.

I have played a number of rounds over the years at Cape Arundel Golf Club, and it encapsulates so much of what is great about Maine and the way golf is conducted there. Walter Travis may have designed his best greens at Cape Arundel, and at 5881 yards, it looks easy on the scorecard. However, the greens, the Kennebunk River, and the slightly blind shots will keep your ego and scorecard in check. Perhaps most importantly, like many courses in Maine, it is listed as semi-private and they mean it! Back down at courses in the “Lower 47”, semi-private often just means a public course that raises prices and/or creates a weekend membership at an inflated price. At Cape Arundel, there is a REAL membership that cares for the course and they genuinely want to share it with the world. There is no need to be private as they have found a healthy balance between the locals who “own” the course and the tourists who “rent” it.

In the book there is mention of George H.W. Bush just being one of the guys at the club. I have seen this firsthand, I have seen lobstermen in flannel shirts enjoying an evening nine, and I have seen all kinds of people in between at Cape Arundel. When Mr. Moore said they were looking for a title, I blurted out “The Way Golf Should Be,” which was in contention but ultimately dismissed as too close to the Chamber of Commerce slogan from which it was derived. But golf in Maine is truly done the way it should be.

Is it a stretch to suggest that the game remains truer to its roots in Maine than many other places wherein the game has been junked up with non-essential creature comforts?

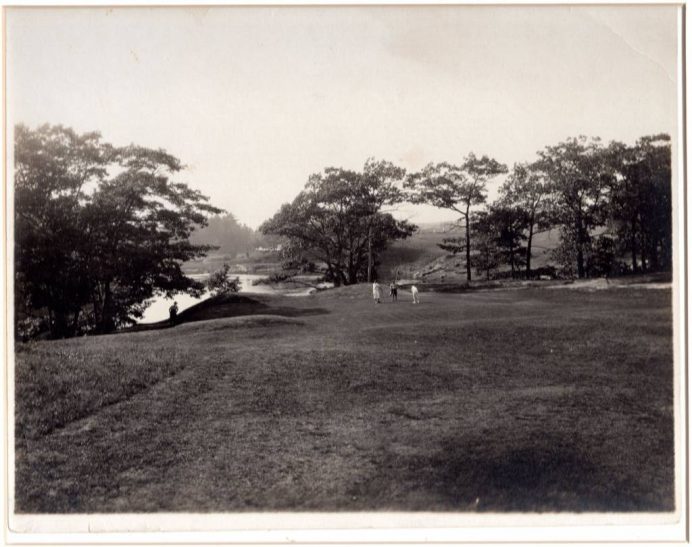

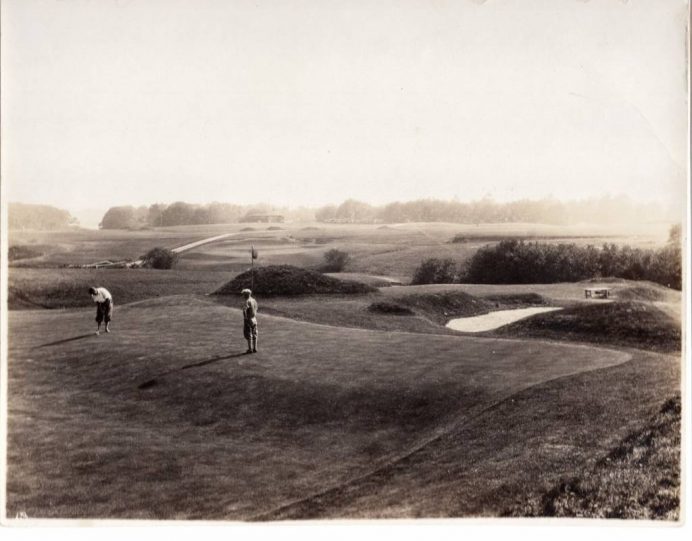

.Talk about lay-of-the-land architecture! This postcard of Lake Kezar is courtesy of Lovell Historical Society.

A New Yorker arranges thirty-six holes in an affluent town for his initial Maine trip. He goes into the first pro shop –

“Good morning. Can I get a small bucket to warm up?”

“Sorry, no range here.”

“OK, can I get like a muffin or something?”

“Ah, no.”

“Coffee?”

“Nope.”

After lunch he arrives at the second course –

“Can I please get a small bucket?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“How about a granola bar?”

“We don’t have that, sorry.”

“Diet Coke?”

“Ayuh, there’s a vending machine on the twelfth fairway.”

Well, Sweeney’s first trip wasn’t exactly like that, but close enough for this Yankee humorist. Yes, Maine golf is uncluttered and unpretentious. The modest clubhouses with wooden shingles are my favorite aspect of this.

When and under what circumstances did golf first come to the state?

Golf came to Maine in the mid 1890s, at summer destinations in some pretty far-flung parts of the state. Kebo Valley and Mt. Kineo were served by public transportation, but now that I think about 1895, playing some golf in the middle of Moosehead Lake and then having supper in a 400-seat dining room sounds a bit like walking on the moon.

What prompted the formation of the Maine State Golf Association in 1917?

The association has blossomed into robust charitable entity, but it seems to me that in 1917 they just wanted to find out who the best golfer was.

The author John Galluzzo makes a fascinating observation about what the advent of the automobile meant – both good and bad – for golf. “After 1910, the era of the grand Victorian hotel drew to a close, and the rise of the roadside inn commenced.” Which course loss do you most lament?

I had a pretty good reckoning with nostalgia while doing this project. On the one hand, I was haunted by the loss of so many courses – some in spectacular parts of the state like Lamoine, Brooklin, and Phippsburg, and some built in the 1800s like Conduskeag, Oquossoc, and Squirrel Island. On the other hand, where are the pictures of these courses? They were just mowed fields, right?

There is no great Lido-esque course that vanished off the map. For its combination of name and location, I therefore lament the absence of Rascohegan Golf Course on MacMahan Island in Georgetown, built in 1900. However rudimentary they were, or how few holes they had, I did become enchanted by these courses while looking for any evidence of them.

John Updike gets the epigraph in this book. How does he capture the New England golf experience?

I knew nothing about Updike until I read Rabbit at Rest in 2007. I found it extraordinary from the first pages, and I could not believe my good fortune when a prolonged golf scene appeared early on. Then I found out that he was a golfer, and that he had even found time to write an essay about watching golf on television. The epigraph, which can be revealed by purchasing the book, is as good of a description of golf’s allure that you will read.

His essay “The Yankee Golfer” begins with a tossed-off description of New England as a “shaggily mittened hand waving good-bye to Europe” and ends with a lament about “the faithless course frozen and glazed, forgetful of all the good times we had together.” It’s a decent summary of golf in our neck of the woods but as the best golf writer, he has done much better – “the fat shot that sputters forward under the shadow of its divot, the thin shot that skims across the green like a maimed bird,” etc.

What is the effective playing season in Maine? The MSGA has 125 tournament days a year so the Maine golfers appear to be quite an active lot!

I am going to give us credit for a full seven months, from mid-April until Thanksgiving. As for the tournaments, the association is blessed to have just the right demographics for a weekend event most Fridays and Saturdays during the season. This schedule is the heart and soul of the MSGA – we play all over the state and dozens of regular foursomes and all sorts of other people show up week after week.

What three courses make the most of their coastal setting?

First place, and it’s not close, is Samoset. There are about 1,400 yards of coastline here, and every single inch of it is devoted to golf. Yes, it’s a resort-style course, but there are many solid holes, there’s a double green that sticks out into the bay, and the long views from the harbor, to the islands, to the open ocean, are omnipresent.

…………………To suggest that the 4th green at Samoset takes advantage of its setting is an understatement!

Next there is Prouts Neck, where you hit practice balls into the dunes, play the first two holes directly next to the beach, and re-emerge periodically onto Saco Bay. It is a secluded and special location.

Finally, Grindstone Neck, an ancient and raw layout without bunkers, takes you within a few yards of Frenchman Bay for a spectacular panorama, and has a cool double fairway on the east side of the course where you can gaze out onto a completely different body of water where people park their boats.

What three courses feature the best topography?

Again there is a very clear winner, and that is Springbrook in Leeds. The holes are arranged in an ingenious fashion over and around a modest river valley, where there are humps and bumps of all shapes and sizes. To me it brings Eastward Ho! to mind, and others have compared it to National Golf Links of America.

Mingo Springs is another thrill ride. The waves on the first fairway are pictured in the book, and there is not a dull hole on the front, which is perhaps the quirkiest nine in Maine. There is a flattish part on the back, but from there you can see two lakes and a mountain range.

Portland County Club, at the other end of the glamour spectrum from those two, occupies a diverse and exciting landform. The front has ravines that envelop the back and sides of the first green, an inlet that frames the par threes, and sandy shores by the eighth hole. The back is more bold, built on and around ledges that provide some fairly steep features.

What three designs end at your favorite green complexes?

The gold medal goes to Prouts Neck, which has roughly sixty greenside bunkers, many of which are tied in perfectly in the style of the Australian sandbelt. On top of this there is great variety of slope, contour, greens that are pushed up or continuations, false fronts and false sides.

I’ll go with Belgrade Lakes next. I never realized how good these greens were until I played them (in an exhibition with other directors) double cut and rolled at the 2016 Tri-State Matches. These are extreme and enormous greens in the modern style. The steepness of the slopes and the magnitude of the contours are at times outrageous, but there is balance and pace in there as well.

Cape Arundel has generated more inquiries from the nerds at GolfClubAtlas than any other Maine destination. The greens here are surely tops in the state for character and old-timey charm. The fallaway on seventeen, the shelves on ten and eleven, the pimple on five, and the insanity on eight are instantly memorable. I prefer the more subtle integration of the features on world-class greens such as one, fourteen, and eighteen. It all adds up to something very different and enjoyable.

The one of a kind 11th green at Cape Arundel is additional proof that Walter Travis was one of the all-time best at building interesting putting surfaces.

Let’s track Kebo Valley as an example of how a Maine club progressed in three (!) different centuries.

The land at Kebo Valley began as a horse racing track for the rich and famous, and Herbert Leeds designed the first nine. Like many courses in Maine, it was battered by the Great Depression and nearly finished off by World War II. This haunting quote from their centennial book says it all – “In June of 1943, Club Secretary and Treasurer John Whitcomb reported only $600 in cash and a note overdue to the bank for $3,700. Membership had declined to just 32 members and seven of those had not paid their dues.” The members realized what a gem they had, clawed back by instituting the European semi-private model, and today you can purchase a membership for $1,080 while visitors pay a green fee that is high for the state but quite modest for a tourist on holiday.

What are three of the most unusual holes in Maine?

For good quirk there’s the third hole at York Golf & Tennis. Many a first-time visitor walks right past the this tee and over to five, because the magnificent punchbowl green is hidden seventy yards behind the top of a scraggly hill. For puzzling quirk there is the iconic seventeenth at Cape Arundel, whose tiny green features a three-foot plunge from front to back towards the river.

And for sheer implausibility there is the par-five double-dogleg fifth at South Portland Municipal – 372 on the card, 342 down the centerline, and 304 as the crow flies. The first turning point is at 160 yards, with a hard forty-degree turn to the right. The second is at a very quick 280 yards, at which point the fairway lurches an entire sixty degrees back to the left. Yes, I would sit there all afternoon watching pros trying to drop one over the tree-line and drive the green.

Which three golf course architects did the most to shape golf in Maine?

Alex Findlay got the ball rolling by taking a good number of the aforementioned primitive courses into the modern age. I am unsure of what is left of his work in Maine, but I believe that if you played Megunticook, Tarratine, or Grindstone Neck, all so raw and bunkerless, you would get the correct feel.

Donald Ross got hold of the best pieces of land and left behind a small number of very fine courses. He also mentored local professional Alex Chisolm, who went on to design three solid courses – Martindale, Sanford, and Lakewood. And by the way, when I finally sat down to read about Ross, I could not really get my head around the volume and quality of his life’s work.

Nevertheless, Wayne Stiles is our guy, the one who built the most courses, put in the days and weeks on-site, designed greens and bunkers with the most flair, and left behind what is perhaps our best course, Prouts Neck. He kept a home on the ocean in Kennebunk and is buried in Portland. If only he had been able to complete all of his eighteen-hole designs here . . .

Wayne Stiles put great care into his greens, as evidenced by holes six, seven, and eight at Wawenock. Photograph by Brad Tufts.

What’s your favorite course to open in Maine since 2000?

Fox Ridge in Auburn. Great topography and conditioning, a diverse layout, and they are close by at an attractive price point. They have never hesitated to rent their course to the association, including a few Maine Opens, and this has become a favorite place to identify the best golfer.

What is your favorite bit of restoration work during that same time frame?

I have had great fun doing research for this interview, but nothing compares to last week’s visit to the Boothbay Harbor Country Club. Flavored-vodka mogul Paul Coulombe purchased the club in 2013; at the time it was a solid Stiles to which a homegrown back nine had been added. What he did there after spending tens of millions is simply jaw-dropping. Bruce Hepner rebuilt seven greens, added many bunkers, and redid most tees. There is also brand new drainage and best of all, a massive tree clearing. Did I mention the four-acre driving range, the 32,000 square foot clubhouse, the eponymous steakhouse, and the deck at the turn with an outdoor kitchen and long views to the west?

I know that all of these fancy extras are at odds with the aesthetic we have been discussing. First, I would remind everyone that the course now plays firm, with dramatically enlarged corridors. Second, despite his propensity for architectural gigantism, Mr. Coulombe is a man of good taste. The clubhouse somehow lies low to the ground and its interior is on a human scale. Some people may laugh at a fellow who opines on the the density of the ice cubes that are served at his bar, but I am a huge believer in attention to detail, and these details, which have basically been donated to Maine golf, are going to live on for a very long time.

Going forward, how will the Maine State Golf Association help courses achieve their optimal presentation?

We work with superintendents on everything from pesticide regulations to Audubon certification, and we help facilitate the USGA Green Section club visits for agronomical assessment. When we approach major tournaments we urge clubs towards sensible practices – rough that exacts a penalty on a ball that you can find, fast but sane green speeds, bouncy turf.

Every little bit helps, including this interview on a site devoted to the frank discussion of great golf. I hope that readers who are coming here for the first time will stay a while, poke around, and see how many courses around the country have broken out the chain saw and seen radical improvements.

The simplicity of golf in Maine remains one of its strongest allures. The postcard above of Wilson Lake is courtesy of David Cummings.