Feature Interview with Lorne Smith

July 2015

As found on his web site, www.finegolf.co.uk, Lorne Smith was born in 1949 and has lived in the Midlands since the early 1970s. He is a member of Northamptonshire County as well as Royal Dornoch, to which he has travelled every year since the mid 1980s. He has played some 450 golf courses – in Australia, South Africa, S.E. Asia, America and Europe – and realised one has to adapt one’s game to the type of grasses used in different climates. He believes that those in the British Isles are incredibly lucky that the finest grasses for golf grow naturally in that temperate climate and that those who love the fine running-game must not be complacent in the face of the enormous commercial pressure to distort Britain and Ireland‘s wonderful heritage but work to spread the word and support their local clubs to pursue appropriate policies.

When and why did you start www.finegolf.co.uk? What is its purpose?

www.finegolf.co.uk is an independent campaign for fine ‘Running-Golf’ in contrast to ‘Target-Golf ’.

I have been running an International Executive Search Consultancy (head-hunting) for thirty years and when it fell off a cliff in 2007/8 this gave me some time to establish www.finegolf.co.uk to grow and give me an interest as I gradually commercially retired.

FineGolf’s original objective was an updating of Frank Pennink’s 1962 Golfer’s Companion that reviewed 128 of the finest courses in GB&I. Having played them all over the previous 40 years I extended the number to the finest 200 and in the last seven years there have been some (albeit few) changes and this is from a total of some 2,800 golf courses in Great Britain and Ireland (GB&I).

Having discovered Jim Arthur’s bible Practical Greenkeeping I realised the fundamental aspect that made the golf of these cool-season climate links, heathland, downland and moorland courses more enjoyable to play was the tight, firm turf, while the design, environment and ethos of the clubs helped the overall enjoyment.

Does FineGolf have a commercial objective?

As it has gained credibility, some companies at the forefront of Research and Development into ‘natural’ ways of greenkeeping have wanted to be associated with the FineGolf brand and they help me pay the running costs along with some of the finest accommodation advertising and the project, I’m pleased to report, now washes its face.

If some rich Running-Golf enthusiast wanted to buy-in and invest in growing the FineGolf brand, while leaving me to run the editorial I would be happy to talk! In the interim it is run on a shoe-string with help from some of the finest Running-Golf clubs and an expert Advisory Panel.

How does one subscribe to your email newsletters? They are my favourite in golf.

Press the Newsletter tab on the website and enter name and email. It is supplied free every two months.

Unlike the two other UK newsletters, Michael Coffey’s GCS or Tim Dickson’s Golf Quarterly both of which I rate highly, FineGolf is a campaign and therefore wants to grow its influence rather than simply make money. So we are unlikely to move to requiring a subscription.

Please detail the qualities that enable a course to be considered ‘FineGolf ’.

Firstly, in cool-season climates there is a greenkeeping dichotomy between ‘fine’ and ‘weed’ grasses. This is most easily recognised by golfers who have played a few courses, as the distinction between ‘Running-Golf ‘and Target-Golf ‘.

Americans talk about their love of links golf, which is fine but links are only part of the fine ‘Running-Golf ‘ concept, not its definition. My criticism of the brilliantly researched True Links by Peper and Campbell expands on that issue.

So natural, traditional greenkeeping that promotes the agronomy of Browntop Bent and Fescue grasses in competition with annual meadow grass (Poa annua) is the key first quality.

Secondly, design. The classic ‘Golden Era’ designs of the ‘Strategic School’ are more enjoyable to play than the bulldozer-built, repetitive, ‘penal’-design, par 72 ‘Championship’ courses created in the 1980/90s ‘Target-Golf’ era. For example The Belfry and Celtic Manor are both attempts at creating ‘golf-hotels’ near conurbations on badly–draining land. They bought the Ryder Cup to raise their own profiles: money talks.

We are lucky though that many of the finest GB&I clubs are member-owned and they know their brand is best associated with ‘Running-Golf’.

The design answer in summary is ‘naturalness’, ie blending with the environment of the site and the movement in the ground.

The all-year-round firm, true, running, strategically well designed course is the ideal.

What is the overall trend in GB&I: are courses becoming ‘finer’ or not?

In the 1980/90 golf boom, when it seemed every farmer was diversifying into building golf courses, ‘Target-Golf’ was the fashion.

Since the Millennium, investment in building courses has changed. The entrepreneurs have been building ‘Running-Golf’ courses using ‘fine’ grasses. See the Pitchcare article for detail.

Many of the classic, traditional ‘Running-Golf ‘ courses were also over-watered and fertilised and now have Poa anuua dominated greens, but at least their clubs do not like it pointed out to them that they have ‘Target’ greens! This is particularly prevalent around London.

Walton Heath is a key example of a wonderful club that has re-established its heathland environment with tree take-out and heather recovery that has gorgeous ‘running’ fescue fairways. It will be fascinating to see if it bites the bullet and follows through a change to fine grasses on its greens. But species change is not just about who is the greenkeeper. It is also about whether a vision of improvement can be sold to the members and that requires leadership.

Elsewhere in England others among the finest old clubs are going through the species change. For example; Hunstanton eight years ago had receptive, fast, shaved Poa annua greens that died from disease. They now have healthy, all-year-round firm, true, smoothly running Browntop Bent/Fescue greens, with improving aprons and fairways. Notts (Holinwell) with a design that could host the Walker Cup if it wasn’t predominantly Poa annua, are also making successful moves down the fine grasses route.

Are there misconceptions about what constitutes a well presented golf course?

I enjoy playing courses that challenge me and make me consider my strategy on each Tee. Imagination, improvisation and creativity are so much more important than the requirement of power for enjoyment, even if by definition everybody wants to hit the ball as far as possible. (As an aside, a de-powered ball has to be one of the changes that needs to be introduced to stop courses having to be ever lengthened).

A fine ‘Running-Golf ‘course browns off in the summer. Lush, dark green, striped, soft fairways with fringes of rough around bunkers and no run-offs from the greens are more representative of the ‘Target’ era. Firm aprons cut short and giving a consistent bounce for the ‘bump-and-run’ percentage shot are crucial.

Fine courses have no need to look ‘pretty’. Smart is OK but tidying up a few rabbit scrapes and sandy rough areas are just not a priority. The rough, inconsistent pebble paths at Rye for example are a delight.

You have a unique reviewing style of highlighting agronomy. Where has that understanding come from?

Instinct, from fifty years of playing all the finest GB&I courses.

As FineGolf allowed me to developed contact with the greenkeeping world I have tried to learn from the experts. For example the best two UK experts have kindly joined my Advisory Panel.

My skill, perhaps developed as a head-hunter, is to identify the key issues, while interpreting the technical into the language of the ordinary golfer.

Somebody said to me recently. “You were seen initially as a good reviewer. You are now rattling a few cages and you are doing traditional golf a great service.” I don’t want to upset anybody and always work with club secretaries to check accuracies and gain suggested improvements to reviews, nevertheless FineGolf is a campaign and exposure of the truth does not always go down well with some commercial interests. So be it. An independent voice can only help the long term growth of the game.

How do televised golf events help or hurt your efforts?

Most golf journalists (and some of those interested in design!) have little understanding of agronomy and its crucial role in enhancing the design and defining how best to score well. TV commentators are similar and focus on the numbers around winning rather than the ‘how’. Much of their commentary is dumbed down with the idea that excitement is all in the hyped, exaggerated spectacular. The ball pitching and stopping by the pin – ‘What a wonderful shot!’

The US Masters is the opening of the season for the Northern Hemisphere and is a great event and golf spectacular where we all know the last nine holes backwards. It is played on a soft, pretty, but artificial course. Unfortunately many ignorant golfers put pressure on their home greenkeepers to create a course like Augusta. It cannot be done with a normal budget.

The recent commentary on the US Open at Chambers Bay has raised the issue of agronomy for almost the first time to the headlines. (We must not forget to thank the USGA for that). Was the media ready with expert agronomists/greenkeepers available to explain the issues? No. Why not?

Part of the reason is that apart from the travel and luxury product companies who hope to catch the comparatively wealthy golfer, the money is made in golf by the chemical fertiliser and pesticide companies and the golf equipment manufacturers. Their primary commercial interest is in ‘Target-Golf ‘ rather than ‘Running-Golf .‘ They would prefer that the US Open at Chambers Bay be not seen as a success. (One should add for completeness that the golf maintenance equipment manufacturers seem to play a more neutral role on this issue even if fine grasses need less cutting!).

Water is becoming increasingly scarce in the US and this may actually help combat soft, squishy conditions. What is the situation in GB&I?

The addition of automatic watering systems to GB&I golf courses in the 1960s was a primary reason that started the ‘Target-Golf‘ boom with traditional Browntop Bent/Fescue greens being invaded by Poa annua.

Many GB&I clubs have recently invested in reservoirs to capture cheaper winter water while modern computerised systems allow more precise watering.

A drought kills off a good lot of Poa annua with their short roots, while Browntop Bent/Fescue grasses are drought resistant with deep roots. High cost and scarcity of water in cool-season climate areas favours ‘fine’ over ‘weed’ grasses.

Speaking of British courses, are there examples of clubs that have gone from soft/boring point-to-point golf to something more exhilarating? What are the keys to that transformation?

Let me introduce an aspect that puts your question into an appropriate framework by saying:

1) that one of the things about cool-season climate greenkeeping is that it takes years to build a fine grasses agronomy with the natural soil biology and all the bugs and fungi you want. However, one dose of the wrong chemical fertiliser/pesticide can put back a course for years, killing the soil biology and boosting the environment where weed grasses thrive. So from bad to good is a slow process and if a club is in denial that it has a problem, the greenkeeper is on a hiding to nothing and best to keep his head down and keep managing the Poa.

2) All the courses in FineGolf’s finest 200 are exhilarating but let me nevertheless give examples of some that have further improved.

Carnoustie is an example of a course that was removed from the Open Championship rota. It was in appalling condition after the municipal owners treated it like a park in the early 1980s. One of many peoples’ heroes John Philp, a Jim Arthur adherent, recovered it.

I was disappointed with Waterville, West Ireland when I played it in 2000. It has a wonderful environment and they were lucky that Nick Park bought a house nearby and the Club to their credit listened to him and backed Mike Murphy who has turned round the agronomy there.

Two other inland courses that are hardly boring but have been transformed recently are Luffenham Heath and Notts (Holinwell). Gordon Irvine has been the consultant who has given these clubs’ two able greenkeepers the confidence to make the grass species change.

Of course there are design tweaks and taking out of trees, rebunkering etc etc but it is the agronomy change that gives the platform and drive to all the other good changes.

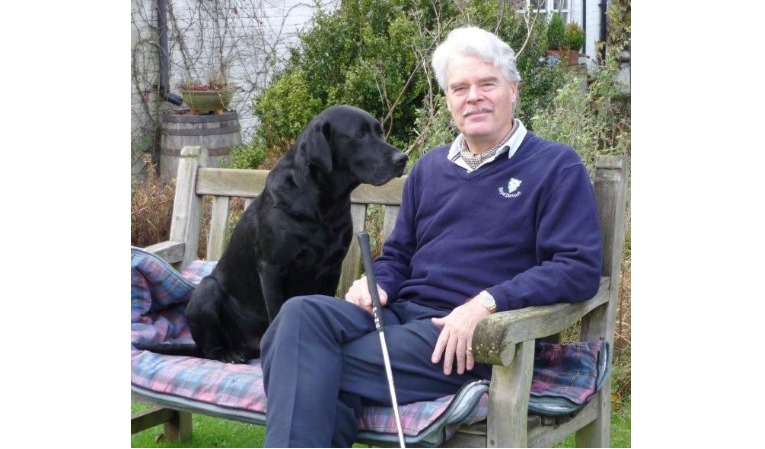

Lorne on his way to winning the Davidson Trophy during the 2012 Carnegie Shield week at Royal Dornoch.

How much tolerance in your evaluations is there for some annual meadow grass (Poa annua) as pure fescue courses are so rare? What are three examples of courses that you downgrade because their grass schemes are poor?

As Jim Arthur said Poa annua is the enemy that is never ever wholly defeated, so of course there are compromises needed. But when aeration, top-dressing and overseeding are reduced, you know the course is going in the wrong direction!

The Berkshire has two courses designed by the brilliant and creative Herbert Fowler that for three months in a dry summer can be most enjoyable and with all the other elements of beauty, ethos, sociability, facilities etc it easily gets into the finest 200. But their agronomy is almost 100% Poa annua and though on well-draining heathland the greens are puddings in the winter and therefore it rates three stars not five.

The Addington, in South London, has a tremendous Abercromby (ie?!) design but the new owners have softened and greened it up. What a pity, even if Wodehouse’s bunker has not been changed!

Trump Aberdeen with its overseeded ryegrass fairways also loses a star.

Nairn’s marketing seems to have relied on the James Braid 1920 quote of its ‘finest turf’. There is hope that with a new secretary and greenkeeper they will lead a recovery from a domination of Poa in their receptive greens.

Machrahanish Old is a wonderful Old Tom Morris design but the aprons and greens are soft, seeding Poa. Next door at Dunes they are trying really hard to go down the fine grasses route.

What are three examples where the turf is so firm, so firm running, and such a delight, that the joy of playing the course exceeds the actual design merits?

An obvious example is flat Prestatyn in North Wales. As the grasses improve from hole seven onwards the course becomes really enjoyable.

Freshwater Bay on top of the Isle of Wight downs has tremendous views but it is the fine turf that gets it into the finest 200.

St Anne’s Old Links near Lytham is almost as flat as a pancake but the agronomy ensures that it is awarded two stars.

Please define your ‘Joy-to-be-alive’ factors. What is the expression’s origin? I love it!

I do not have the time or inclination to list courses in a prescriptive order of ‘best’ ‘great’ or ‘top’. I star them between one and five on a ‘Joy-to-be-alive’ rating. There are some 30 that are five-starred. It is a totally subjective assessment though I do try to define the factors that are important to me. The phrase, along with ‘Running-golf’, is an attempt to summarise why we are passionate about these types of courses.

Is it our balanced attempt to both live with, while also controlling, nature’s wildness that is an aspect of FineGolf ?

FineGolf transports the spirit away from life’s worries and renews it.

How do rough lines factor into your assessment?

Firstly the most important issue is the nature of the rough. High wavy fescue (or fps) that looks daunting but within which you will find your ball at the bottom and be able to get back out with the grass tangling the shaft, is an ideal. If the rough is penal being thick, heavy and lush then it is not much fun.

Paul Gray has recently written a fascinating article on the width of fairways published on the FineGolf website. There can be no doubt that strategic play requires width as much as it does firm turf. Nevertheless there is perhaps an element in Tom Doak’s minimalism at The Renaissance and Mark Parsinen’s openness off the tee at Castle Stuart, both of which work well for their clientele, however and at the cost of criticising two of the world’s finest living designers, in comparison with Royal Dornoch for example, where the hazards and movement in the ground are so tight to the positions that offer the best line for your next shot, (and this is also without being overly penal on the high handicapper), the width loses something in their designs.

I am a traditionalist at heart and enjoy seeing good fine rough used to catch the ball that runs out of position. The classic case was when in 1999 they grew the rough in at Carnoustie to penalise those Open Championship players who did not take the risk of Hogan’s Alley, was to my mind quite fair.

In simple terms the scratch golfer needs to be challenged by tight hazards while the recreational golfer is permitted an easier and wider route to the green. It is only on ‘Running-Golf ‘ courses where both can be accommodated. On modern ‘Target-Golf‘ courses the hazards are so penal (see Donald Steel’s take on this) in order to challenge the scratch player, that the recreational golfer simply loses balls in the water and can’t achieve the carry etc.

Does bunkering, its style and maintenance have much impact on your assessments?

A bunker should be something to avoid. These flat traps around American greens, surrounded by penal rough, where some players prefer to finish, are not clever to my mind.

I like natural bunkers that fit the course, gathering in the ball and they should be deep enough to be a definite hazard.

The sand colour needs to fit. West Sussex has wonderful white sand, whereas white does not work at the ironstone-coloured Northamptonshire County.

Ragged lines, such as in a Simpson or Fowler design, on the right heathland or links environment, are beautiful. Crisp Colt or Braid bunkers need to be seen, and I like the increasing use of heather tops.

Those who complain about inconsistency within bunkers should try harder to avoid them!

In the United States, many greenkeepers are college graduates whose focus is on mere management as opposed to the old fashioned keeper of the green who lived on the premises and regularly had his hands in the dirt. This trend has been both good and bad. What is the situation in Britain?

I am not in the profession and any comment I make comes from meeting lots of greenkeepers and recognising the incredibly difficult though enjoyable job they have. Meeting the greenkeeper when I visit a course tells me more than anything else. Some ‘well-educated’ Master Greenkeepers are clever but selfish and over-complicated.

The older-fashioned, hard working, hands-on ones can be the best. Take Billy Mitchell, 50 years at Perranporth, Cornwall, as an example of somebody who looks after a glorious, quirky James Braid course that is as close as possible to 100% Browntop Bent/Fescue grasses.

The younger ‘educated’ ones are usually better at communication which is essential if a course is going to be taken through species change. Any club membership needs to be given a vision of where the future lies and its advantages, as well as the more mundane month to month programme of maintenance, so they are also excited by the opportunity of improvement.

But I am told that good natural greenkeeping is really quite simple, depends on the weather and not only demands good management and motivation of the troops, it also requires hands-on detail. No course is the same, (though the chemically managed ones that have effectively dead soil might look similar to each other) and knowledge of a site is crucial.

I recommend greenkeepers to have a Frequently Asked Questions page on their club website. If something is written down it has to be thought through.

Some American clubs seemingly boast about how high their maintenance budget is, as if that was a badge of honour. Do British clubs display more commonsense?

Nick Park before he died was looking into a way of tabulating maintenance budgets against greens performance. I believe his instinct was that there would be an almost negative correlation!

He had achieved half of his objective by introducing the Greenstester to give greenkeepers an affordable objective measuring tool which, when combined with The R&A’s ‘Holing-out-test’ to objectively measure putting performance, was a real breakthrough.

Jim Arthur used to say that the courses with low budgets were usually providing the finest greens as they had no money to spend on fertiliser and pesticides! The examples of Prestatyn and Bull Bay in North Wales where they have only four greens staff each and fine greens, seems to fit that claim.

Nick Park in an important FineGolf article believed that for golfers and for clubs, valuing the golfing experience is today moving into a different era. Golfers will vote with their feet, and seek out clubs which can prove that their surfaces are delivering the goods all the year round – at an affordable price. And clubs which focus on an effective audit cycle – freely available through The R&A – will have the inside track.

The other additional issue to consider here is how to objectively measure the percentage of fine versus weed grasses in a green. A rule of thumb can be made by using a magnifying tool but Nick was also trying to get the STRI and the commercial developers of fine seeds, such as Barenbrug and Johnsons, to research a way of using the DNA of grasses collected in a mower’s box. The problem of course is that money needs to be found to fund the research. The big chemical company boys have little interest in funding something that will not help them sell more of their products!

What three courses are you most looking forward to visiting in 2015?

Having already played Ganton, Royal St George’s, Rye, Royal Porthcawl, Royal Dornoch and Walton Heath this year, I suppose the invitation to play Royal County Down, Royal Portrush and Royal West Norfolk must answer your question. And I will add a fourth, Skibo.