Feature Interview

with

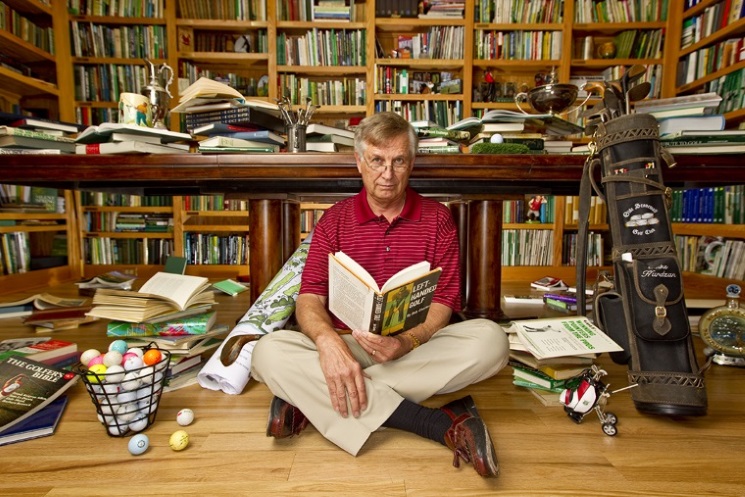

Dr. Michael Hurdzan

January, 2015

How/why did you get into golf course architecture?

My dad was a self-taught, very good golfer who might have tried the tour but in the 1930s and early 1940s there was no money to be made. He had a family, and a world war started. So in the 1950s he became a part-time teaching pro at a family owned 9-hole golf course called Beacon Light on the west side of Columbus. At age six or seven I was a shag boy for his lessons, then became a caddy at age 10, and became a greenkeeper at 13. Beacon Light’s owner, Jack Kidwell, was one of my dad’s best friends and also a great player, as well as being a Class “A” PGA Pro, Class “A” Golf Course Superintendent, and a fledgling golf course designer. So in 1957, Jack started taking me, at age 13, with him to job sites to carry the grade stakes, chop brush, hold the survey rod, etc.

It was the most magical thing that I could imagine – taking farm ground and woods and turning them into a golf course. It was like watching a slow-motion birth to see a golf course materialize from nothing in very measured ways. I told Mr. Kidwell – “This is what I want to do for the rest of my life,” and he replied, “Do what I tell you to do and I will teach you how.” Except for some time away at graduate school and the Army, we worked together until 1985 when Parkinson’s disease finally ended his active involvement and I took over the company. We kept Jack involved until the mid-1990s when he had to go to an assisted living area – so I am proud to say that I had Jack for 39 years as my mentor, business partner and friend; he was like a second father to me. Both my dad and he taught me the fundamental principles of golf, golf course design, and life, and they have served me well. I was blessed to have these two men in my formative life.

What comes to mind when I say “Dr. Who”?!

That British science fiction show has been around since the early 1960s and it is still going strong despite about 12 or 13 different actors playing Dr. Who; so everyone has heard of the show. The standing joke in our office in the 1980s and early 1990s was that I was the Dr. Who of golf course architecture because no one had ever heard of me. It started when a past client relayed he noticed that when people finished playing his golf course and would say how much they enjoyed it, they would inquire who had designed it. He would say “Dr. Hurdzan,” and they would often quizzically reply “Dr. Who?” As our designs garnered more media attention the Dr. Who title became less accurate, but I still do enjoy a great deal of anonymity among the popular golfer, which drives my son and business partner, Christopher, nuts, given the marketing-heavy nature of this business. But, that’s just who I am.

What is a favorite par 3, 4 and 5 you have designed? And why?

WOW – tough question, because I have a lot to choose from, but if I had to choose – which I do – it would be these:

Par 3 – 15th hole at Bully Pulpit, Medora, North Dakota, which plays from high, windswept tees at the top of a badlands hill, across a deep, wild ravine, to a small green placed at the base of a small rocky knob. The wind can blow so strong up there it is hard to stand up let alone play a golf shot and the 360 view is unencumbered by anything manmade. No wonder Teddy Roosevelt loved that area so much.

Par 4 – The 9th hole at Devil’s Paintbrush, Caledon, Ontario, Canada – 383 yards of sheer fun and terror. It is a bit of a blind drive over a hill to an extraordinarily wide fairway, but then the fun starts because the approach is to a huge double green (shared with #2) that is four or five clubs deep, with target areas separated by some pretty wild contours. To play it is to never forget it.

Par 5 – The first hole, West Course, Ottawa Hunt and Golf Club, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada – 520 yards of double dogleg, an original Willie Park, Jr., design that I believe I enhanced significantly. Depending upon where one hits his drive, they could choose to play their second shot over the cross bunker out 40 yards in front of the green, or short or to the left of it, each carrying a resulting risk, reward or challenge. I spent a good deal of time thinking about getting just the right target area size and protecting slopes and hazards so that it will never play the same twice, and requires both good thinking and shot execution. The first hole at Devil’s Pulpit is more visual but this hole is more pure strategic design concept.

Your office outside of Columbus, Ohio is revered for its collection of clubs, books, magazines, art work and memorabilia regarding the game. How did you get started?

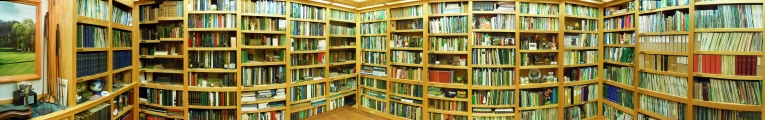

I grew up immersed in golf but really never thought much about the history of it, until Christmas Day, 1968 when I was given a copy of Robert Hunter’s The Links, and George Thomas’ Golf Course Architecture in America. Those books opened a whole new world of golf for me, and I couldn’t get enough. My pastime became book collecting, then in 1972 I met Bob Kuntz who co-founded the Golf Collectors Society with Joe Murdoch, and my collecting really took off. Today I can modestly say that the collection is one of the most diverse in the world with over 6,000 books, countless magazines going back over 100 years, 8,000 wood shaft clubs, untold amounts of ephemera, paintings, sculptures, glassware, silver, etc; and some pretty cool artifacts of golf course architecture.

Golf collecting has expanded my world of golf through the people I share it with, what I learn about its rich history and its colorful characters and places. I have also discovered that golf is intricately woven into the fabric of most English-speaking cultures in ways that most people could have never imagined until they start collecting all things golf.

As a historian, what fascinates you regarding the evolution of the game?

I think the most fascinating thing about golf is how infectious it is to the human spirit. The game is supposedly over 600 years old and it roots or precursors may go many multiples of that, and it has survived natural catastrophes, world wars, depressions and ugly politics. It is outwardly, and constantly evolving in equipment, technique, dress, playing surface, rules, affordability, sustainability, name it!…But literally it still involves hitting a resting ball, with a stick (club) into a smallish hole in the ground. People fall in love with golf and will spend countless hours and money pursuing, trying to master a game that offers nothing more than a cruel, short-lived reward for a day, and challenges you to try again tomorrow. In one sense it is insane. However it attracts people willing to be humbled, who care about sportsmanship, companionship, competition and the environment of the golf course. In that sense, it is magic. Fascinating and fun!

How has your appreciation/knowledge/love of history impacted your designs?

Understanding the evolutionary forces and history of the game, and those principles and concepts that are the most basic and timeless, are the ones that I most enjoy trying to incorporate into our designs. The most dominant concepts or philosophies are “Form Follows Function,” economy in construction and maintenance, affordability and accessibility, economic and environmental sustainability, and healthy, outdoor recreation for all golfers. Truly successful golf courses share those qualities no matter where they are located, when they were built, or how they were built. We bury our dead in golf, for unsuccessful courses either are remodeled to an acceptable standard or they close. Each time one of those basic tenets of golf design is violated brings it one step closer to remodel or death. So by studying and understanding the survivors we can learn the bedrock principles of living, life and golf course design.

“Simplicity is the essence of good taste,” which is why we so revere the work of MacKenzie, Ross, Colt, Park, Jr., etc., who gave us some of the most appreciated golf experiences with simple trappings of earthwork, bunkers and landscaping that have endured the passing of time, unmolested.

What other factors have influenced your designs?

Actually maintaining and understanding exactly, not conceptually, but exactly how a golf course feature must be maintained is critical to becoming a master designer. Spending time mowing, raking bunkers, hand watering, topdressing, doing aerification, hand trimming, etc., all of the little detail jobs that makes a golf course special and understanding how it impacts golf and golf courses is an essential skill set. I do not think a person can really do their best job of designing something unless they understand how it must be maintained and the labor required to do that. Design, construction and maintenance are intrinsically linked and the chain should not be broken, and those most guilty of violating that linkage are those who think that responsibility for maintenance is someone else’s job. There is a triumvirate of designer, builder, greenkeeper that must work together as a team with the solitary and selfless objective of making the golf course the very best it can be with whatever resources they are given to work with.

Please tell us about our mutual friend Tom MacWood. He never seemed happier than when he was scouring through material in your library.

Tom was our most frequent visitor and user of my library – rivaling almost myself. He liked to come in on Thursday or Friday afternoon about 1:00 p.m. or so, and stay until we all left about 5:00 p.m. He knew he had complete freedom of the library which is not something I grant many other people except perhaps the eminent Turfgrass scientist Dr. James Beard and his delightful wife Harriet. So he would always call first, then come visit and get lost in the books and magazines he so loved to explore – the more obscure the better. Once he found something interesting he would gleefully show it to me and explain its importance, then either photocopy or scan it on our machines and soon develop a scholarly article from what he found. He really became part of our professional family and he always had a smile on his face and had a childlike curiosity for all things golf and golf architecture. He was a meticulous researcher, so if he said or wrote something, I would bet on it being spot-on correct. He is missed.

You have built courses around the world and your name is associated to nearly 300 courses. Of course, a few projects got away/never happened. Which three sites that you visited never materialized that had the greatest potential?

Well, for sure I would say the site in Bali, Indonesia, that my former business partner Dana Fry and I visited on a couple of occasions. It was on high bluffs above the ocean, and it had a breathtaking view of the ocean in every direction from nearly every hole. Every designer wants an ocean view golf course site.

Then, there is a site south of Columbus, Ohio that was a kettle-moraine landform left by a glacier. It reminds me of our site at Erin Hills. I say “was” because a sand and gravel company bought it and it is slowly being hauled away. This was inland links topography with great views into the City and perfect natural drainage owing to its sand and gravel soil profiles. Ideal for golf and unusual for central Ohio.

The third one might be a site on the west coast of the Big Island of Hawaii in the lava fields near Puako Beach. It was a series of wide valleys and broad ridges that were wide enough for golf holes so lots of natural lava areas would separate the flow of holes without much earthmoving.

For sure, and I am not at all pandering, the site at Inverness, Canada, now Cabot Links, must receive my honorary mention. I’m forever thankful it lived up to its world renowned potential, which illustrates an important point. That is, hopefully, there comes maturity in every architect’s life where they say “I don’t care who designs this place, but this site is so good it simply must have a golf course, not because of ego, but rather, because it is in the best interest of the game of golf.” And that’s how I feel about Cabot.

How did you become involved in Erin Hills?

There are several different versions of that answer depending on who you ask, and there is probably some truth to all of them. I remember it as first being contacted by Steve Trattner, a young man who was working for Bob Lang, the original owner and developer. Steve was well studied on golf course design and had read my first book Golf Course Architecture, and he recommended us to Bob Lang. Dana and I visited the site and were naturally blown away, and we invited Ron Whitten to join us, and Ron had heard about the site before we did. Perhaps Dana or Ron have different remembrances, but it was something like that.

We had several discussions with Bob and did a couple of simple routings on USGS topo to show him a few concepts. Bob selected us as the design team and then kept buying more and more land, with each new purchase rendering previous routings as obsolete. The final acreage is around 600, and Bob should be credited with insisting on the 15th and 16th holes which are some of our favorites. Ultimately, Erin Hills became a blend of ideas from Dana, Ron, Bob and me, that is neither possible to sort out whose idea was whose, nor is it worth trying (and I suppose it really doesn’t matter anyway). I would say that Erin Hills evolved more than it was designed.

The evil, downhill ninth at Erin Hills with its long slender green is destined to become one of America’s most feared one shot holes. It is guaranteed to wreak carnage during the 2017 U.S. Open. Photo courtesy of Paul Hundley.

Several iterations of Erin Hills have existed in its brief history. When it opened, it featured a Dell hole and an uphill, nearly blind Biarritz green among other blind shots. After a series of changes, much of the blindness has been pared down. Where within those two bookends is your favorite version?

As I said Erin Hills evolved, and although Dana, Ron or I do not object to naturally occurring blind holes, because that is the nature of links golf, most North American golfers do. As a result there was a lot of criticism of the blindness of some holes like #1, #2, #7, #10, #17, and it wasn’t worth fighting over, so those holes were changed to reduce or limit the blindness. Another part of reluctance to change those holes was because our objective was for there to be little to no earthmoving to construct Erin Hills and to correct the blind areas meant a fair amount of excavation. We didn’t resist reducing the blindness other than it added cost and had part of the course as ground under repair.

Today, I must say that holes #1, #2, #7 and #10 still have some blindness but are better because of the changes we made. I personally think that #17 is a poorer hole than before because all of the blindness was removed – or else bunkers should be added for it is bland compared to all the other holes. It has no bunkers and is too easy as a finishing hole despite its length. Perhaps one day the new ownership will permit us to fix that weakness.

A few greens had to be tweaked and one could debate the merits of doing that, other than it made the golf course more appealing to North American golfing expectations. If those original golf features were in Europe, they may not have even been noticed. Originally no grade on any green was changed more than about a foot from how the glacier left it, and we felt that was a hallmark of the course. As greens got ultrafast, some of the slopes were just too severe. We violated the principle of “form follows function” and we had to go back and fix it as I alluded to earlier – we bury our mistakes.

Overall, the golf course is better today than it was originally although I would have preferred to keep the wide fairways that we originally had. No golf course is perfect the day it opens and there are always things on a golf course that can be improved. If the golf course were not for profit it could have existed just fine with the quirkiness that is part of links golf.

Do you agree that course architects should shoulder some of the blame for the decline in the game’s interest?

Yes, absolutely, positively, especially those of us who tried to outdo our competitors with overcooked bunkering, wild greens, overdone earth forms, massive earthmoving, excessive irrigation, plastic rocks and waterfalls, etc. We binged on achieving “the look” instead of favoring playability and creativity – even if it was an obsessive attempt to get the “minimalist” look. We were encouraged to do so by our clients, magazine ratings, pretty publicity pictures, and critical acclaim by people who thought Disneyland was a real place. Golf courses became too expensive to build and maintain, too hard to play, reduced the pace of play, and generally discouraged attracting beginners. It was a huge party for everyone in the golf industry and now we have a hangover, and I don’t think we started to really get well yet. Let us hope if the party ever starts up again that we “party responsibly” and remember how badly we hurt ourselves the last time we were given free reign.

Golf will survive as it always does, but there is no doubt it is changed, or should change, to meet more with the lifestyle of young families who prefer fun, friendly golf experiences over excessively challenging and expensive ones. For example, just look at how “Top Golf” is sweeping the nation. Study its appeal, and apply some variant of that interpretation to golf courses seems a viable way to reverse this decline in participation.

How much responsibility do developers deserve for golf being perceived as too expensive and time consuming? After all, one assumes that an architect is merely carrying out the wishes of the owner.

In my firm and on our projects we worked closely with clients at the earliest stages of design to understand costs and how to control them. For example, on a site for a basic golf course like a mid-level daily fee consisting of multiple tees on each hole, excellent greens, perhaps 60 – 70 bunkers, good drainage, a solid irrigation system and asphalt quality golf car paths would cost perhaps $3.5 million, and could be maintained for $600,000 per year. Or on that same site we could take that well-built, solid, and functional golf course, and inflate the price by two or three times that cost by specifying exotic construction materials, overdesigning the irrigation and drainage systems, building stonewalls everywhere, putting in concrete or paver golf car paths, and landscaping like it was going out of style. But, would the golfer get two to three more times excitement or pleasure from the golf course? Probably not, but the golf course might get a higher rating from the magazine raters, and in theory sell more house lots, room nights, memberships or green fees if those numbers fit their pro-forma for profit we were happy to do it. Does spending more money make us better designers? Absolutely not, but we would never turn it down if we assumed or knew the client had a solid business plan.

On top of that, many developers wanted a “championship” facility – no less than 7,000 yards in length, par 72, minimum slope ratings in the mid 140s, and the more challenging each of these golf features or hazards were the better. There was almost a competition of who could make the most difficult golf course, and we were all competitors – cheered on by the developers and magazine raters. And if you didn’t play this silly game, you didn’t get the “good” jobs and clients. The recent recession was a slap in the face, and now we are remodeling those courses into something more sensible, for third owners who want to be successful in the golf business. Unfortunately, that mentality is still alive and well and living in Asia and the Middle East.

So, YES, some developers could be their own worst enemy. They wanted Top 100 rankings, lost sight of sound business practices, subsequently lost money hand over fist, and now banks and lenders consider all golf course investments as toxic assets. Designers helped hold the golden goose while developers cut off its head.

How should owners structure an arrangement with an architect whereby the course comes in on/under budget and it doesn’t cost a bundle to maintain every year?

Frankly a reputable and skilled design firm should start discussing fiscal matters early in the process, offering cost estimates in the earliest stages of design called “Research and Analysis” or “Site Evaluation,” and give the owner some idea of costs before he or she even starts doing routings. Granted the range may be wide say a million or two, but it won’t be five or ten million off, and then at each successive stage of design refinement thereafter that cost estimate range should get more narrow. Competent designers should also give the owner some idea of what the possible maintenance budget will be, so the owner is not shocked by maintenance once it begins and never ends. We usually end up within 3% – 5% of actual bid amounts and usually the bids are below our estimates, so our clients are never surprised by big numbers and they know we have their fiscal wellbeing in mind.

So the first and best thing for potential golf course developers to do is to spend $100 to buy a copy of my book and see how the golf course development process should run. Then interview several firms and ask tough questions about cost estimating and fiscal management of the construction project. Don’t accept vague or nebulous answers, and don’t be dazzled by celebrity designers for they typically care the least about someone else’s money. Even if a developer doesn’t want to even consider Hurdzan Golf for the design, they should still talk with us, or ask us to help them manage the process.

Because we have been partners in five for-profit daily fee golf courses, we are exceedingly cognizant of cost – both construction and maintenance – which is why over the years we have innovated or championed materials and methods to reduce costs without sacrificing functional quality. Once again, “form follows function” for if one understands the principle they can often improve on the process.

If one were to research the greatest financial failures in golf course development, I believe that they would find celebrity names as the designers. The reason is that they, often through no fault of their own, don’t genuinely understand the business of golf (or the “real” world for that matter), and thus believe in the falsehood that their name on the project is all that is needed to attract golfers, guests and home buyers – long term. Ask yourself how many times have you actually visited a course or bought a product simply and only because a celebrity endorsed it? Golf course developers should never let ego overpower solid business practices, but I have observed it happen with regularity, to even people who should know better. Celebrity is a powerful and blinding influence.

A professional designer should guide the client through the financial processes and costs of designing, building and operating a golf course. Occasionally there are surprises like unknown historic sites, uncharted and buried obstacles, or other craziness like natural disasters (floods, earthquakes, landslides), but even then a good designer should be able to creatively design to solve the issue without just throwing money at it.

What is a specific example of where you opted NOT to do something due to reoccurring maintenance costs?

One large category requiring extreme discretion, particularly in regard to long-term maintenance costs, are all chemically and/or physically abused (e.g., manufacturing) sites considered as adaptive reuse (via golf) candidates. Especially, those containing appreciable volumes of domestic organic refuse where insufficient consideration has been given to the fate of that disposed material. Typically, the major by-product of this organic content decay is vapor (e.g., methane), which is frequently produced in sufficient concentrations to burn or kill turfgrass or toxic leachate which can be extremely dangerous for at minimum, it is an uncharacterized mixture of chemicals. The conversion of physicals to vapor will ultimately reduce the volume of the sub-grade during its natural subsidence, often without warning, resulting in random settling (think sink holes) that can be measured in the tens of feet. To mitigate these unpleasant and unpredictable occurrences, landfills are capped with a layer(s) of relatively impervious materials with the expectation that this cap will remain intact. Therefore, building a golf course on a landfill should be a fill only affair, as opposed to the standard fill AND cut approach. I have found, unfortunately, that even experienced designers don’t fully grasp the function and influence of this containment system, particularly over time, and proceed to, at best, bury irrigation and drainage conduit within this cap, thereby weakening it. Worse yet, is when they advise the execution of cuts, under the refrain “we’ll just repair it later”. I can tell you that it’s rarely quite that easy…

Case in point, about 10 years ago I was asked by a joint County/City commission to design a course on a landfill in my hometown of Columbus, OH. After performing some research and analysis, I told them in explicit terms that ANY golf course on that site would be a maintenance disaster, open-ended financial liability and ultimate failure. They ignored my admittedly inconvenient advice and hired a firm who said “no problem”, and subsequently proceeded to build Phoenix Golf Links. In its brief existence, this facility been through 2 golf operations firms, required millions of dollars in ongoing repairs, is now losing $300,000-$400,000 annually and has been vacant an operator for the last two years. My recommendation continues to be to close it, but I suppose it is the nature of some governments to hope that if they throw enough money at the problem, it will solve itself. The new Ferry Point golf course in NYC is the poster child of this attitude, and for not properly assessing the problems of a landfill BEFORE construction. Thus, a total cost that ballooned from an early estimate of $40MM to a reported $220MM+.

Broadly speaking, other sites I’ve turned down/advised against have displayed high concentrations of soil asbestos, boron and silicate contamination of potential irrigation sources, extraordinarily high soil organic content, areas of poor air movement and unstable soils like those prone to landslide (e.g, the former Ocean Trails GC, now Trump National Los Angeles). Occasionally, we are listened to, but more often than not, are ignored, for a developer can always find a “yes” man for hire in our profession, be they genuinely unaware or knowingly complicit. In my opinion, these are the cases where everybody loses EXCEPT the firm receiving the design fee. Long story short, there are just some places where a golf course should not be built, no matter how deep the funding may be.

What is an example of a course you designed that a) was inexpensive to build b) fun to play and c) where the owner makes a satisfactory return?

One prime example might be Bully Pulpit in Medora, North Dakota, which cost perhaps $1.5 million for the entire golf course in 2003, rated “Best New Place to Play by Golf Digest, remains a “Top 100” Public Course and still costs just $50 to play including golf car. Read the reviews or talk to folks that have played it.

The other prime example is Erin Hills that initially cost much less than $2 million to build in 2007, and is fun to play, but now is at the upper end for public green fees because of The Open fame. Our initial goal at Erin Hills was for a $50 public course and it was designed and built to be profitable at that green fee. It had virtually no earthmoving, very little drainage, California greens with flat tile, two row irrigation, almost no golf car paths, no-till planting, and native grasses were native grasses, and it was reasonable to maintain.

We have dozens of other golf courses that were built equally inexpensively and are very fun to play, but for some reason lack the recognition of the first two. I would love for someone like Mike Keiser to give me a shot at one of his multicourse projects so I could demonstrate our concept for true economy in golf course design, construction and maintenance based on timeless design principles, applied turfgrass science and creative design.

Are there enough affordable courses to induce more young people to take up the game? If not, how would you change that?

You seem to be begging the question here, for I don’t think it is the unavailability or accessibility of golf or golf courses that is keeping young people away from golf – it is the nature of the game itself that is not appealing to them. Without question programs like SNAG, First Tee, Golf after School, and Golf in Schools, Morty’s Kids, and other such wonderful programs have helped introduce young folks to golf, but how many stick with it and really want to play is the real question. If golf was free for young people, as it is in a few places and a few days in the summer, there still would be no overwhelming demand for tee times. In fact a large percentage of the kids that I see in golf programs near where I play are Asian decent, perhaps pushed by parents or inspired by Asian golf heroes. I think any smart golf course operator wants to encourage young people to play for that is their future and will make concessions in price at certain times or seasons…not Saturday or Sunday morning or holidays or other prime dates – that is for certain.

Look at the history of golf starting with Old Tom Morris, who as a child learned to make a golf swing with a curved stick in the streets hitting stones and pieces of coal before becoming a caddy, and that same story continues today, worldwide where kids like Angel Cabrera or Y. E. Yang with a passion will learn golf without it being given to them on a silver platter. As kids we used to lay out our own little golf courses in vacant fields and spaces because we loved to play. Young people have great imaginations and they can be just as happy on a little mowed out golf course in a yard or park, as on an overly manicured one with too many rules and stresses.

So accessibility and affordability are not the big problem, IMO, as much as the stuffiness associated with golf and the time it takes to play. Culturally there is a disconnect, and I have no idea of how to fix it. Family friendly tees are a step in the right direction, but until the game is attractive to pre-teens and teens it isn’t going to grow. Again, I suggest that when we understand and learn to transfer the attraction of, say, Top Golf, to “real” golf, young people will be far more apt to take up the game.

Talk to us about the minimum wage and how that impacts caddies (and indeed the health of the game).

My dad grew up in the coal camps of West Virginia during the Great Depression, and had to start caddying at age 10 to help support his family. As the Depression worsened he had to quit school in the eighth grade to go to work and keep caddying to survive. He taught himself to become an excellent golfer so wealthy guys he caddied for often took him as a playing partner, and subsequently would give him jobs and opportunities despite his lack of schooling. So golf was my dad’s way out of a life as a Depression era, deep shaft, coal miner…and it all started by being a caddy, learning to play golf, being able to mix with social classes far above his, and maintain a sincerity and humility that endeared him to people he met.

I learned the game as a caddy, as did the kids that I caddied with, and most were from underprivileged backgrounds so caddying and golf was also their opportunity for a better life, just like my dad. It was first to the course in morning was the first to get out to caddy, so we would arrive at 5:00 – 5:30 a.m., or earlier depending on how much we needed money to be sure we got out. We were there until 7:00 or 8:00 in the evening and sometimes we stayed all night at the course and slept in the storage sheds. Some days you got out to caddy twice in a day and make “big money” for that time, while on other days you didn’t get out at all so you made nothing despite being at the golf course for 10 or 12 hours. That was caddying before minimum wage laws and no one cared.

Now the minimum wage laws require that a person be paid for every hour “on the job” so spending all day at the course and getting zero pay is now illegal. Golf course owners and leadership became concerned they would be in violation of the minimum wage laws so caddy programs slowly faded away. Some places tried to get around the law by having the caddies wait off property until they had a client, but that led to other sorts of problems and didn’t work either. There were also changes in worker compensation laws and discussions about if a caddy was injured did he or she work for the golfer or golf course, or were they an independent contractor who had to pay taxes as such. Who was going to pay for the caddy’s medical cost? Even today at most clubs where there are caddies they are treated as independent contractors and paid in cash by the golfer. My point is that well meaning laws killed the caddy programs, and with it closed a door of opportunity for a kid who was willing to work and learn the game. Golf is poorer because of that. I was blessed to have caring adults in my young life, as well as being in golf at a time of freedoms from restrictive laws that kill opportunity.

Why is Ohio such a golf rich state?

In my profession I could live anywhere in the world, so I am often asked, “Why Columbus, Ohio?” I jokingly reply that it is not because of the superb snow skiing, nor allegiance to the pro ball teams of which we have none, the big wave surfing sucks, hunting and fishing are long gone. BUT we have some of the greatest golf in the world. We don’t have those other “distractions” but we do have lots of fertile land suitable for golf, generally with lots of water, and a climate and a culture that encourages being outdoors. Ohio, according to Golf Links ®, has 901 total golf courses, Columbus has four Top 100 courses, and there are about 150 golf courses within 50 miles of Columbus, with green fees ranging in cost from $10 up to $49 on public courses. Although golf can be played every month of the year, the prime season is March to November. Columbus is the host city for the Memorial and Web.com professional tournaments, The Ohio State University golf courses host NCAA tournaments and high school championships. Scioto will have the 2016 US Senior Open, and the Jack Nicklaus Museum is in Columbus. We have golf courses designed by Ross, MacKenzie, Jones, Sr., Jones, Jr., Maxwell, Nicklaus, Muirhead, Bendelow, Hills, Kidwell, Hurdzan, Lorms, Wilson and others so we have lots of wonderful architectural styles to choose from. The diversity of affordable, accessible golf in Ohio, especially central Ohio, is phenomenal.

In addition, Columbus is an easy place to live, work, play and travel to and from. The quality of life by any measure is high, especially for golfers. We don’t have mountains, oceans or wild spaces, but we do have lots of great golf throughout the state.

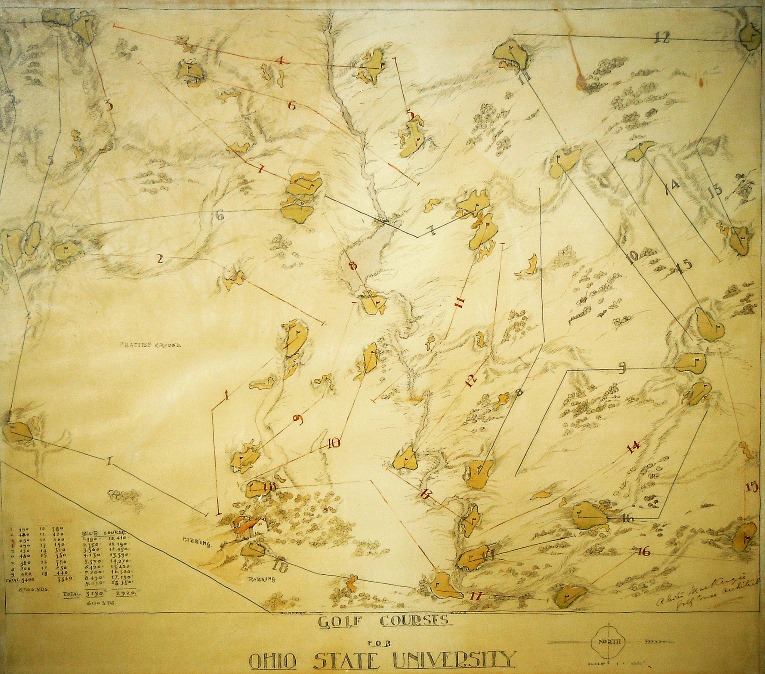

Tell us about the prospects for the second course (Gray) at The Ohio State University.

Alister MacKenzie did the routings for two golf courses at Ohio State – the “Scarlet” and the “Gray” and died before construction. But his business partner, Perry Maxwell came to Columbus to oversee construction, until he was fired by a disgruntled university representative, who then finished the job despite lacking any real experience – and it shows. One can almost walk on each green and tell if it was Maxwell that did the design. So again, the “Gray” course, which we’ll be working on, shows superb green contours presumably designed by Maxwell. Our task is to preserve and restore the greatness of MacKenzie/Maxwell by simply returning the greens and bunkers back to their original shapes and sizes. The Gray course will be over 6,000 yards from the back tees when we are done and will be one of the best, most fun to play, short courses, in the nation, particularly with such a grand pedigree. We are turning the clock back 80 years on this little legacy masterpiece.

What else are you currently working on?

We are finishing a couple of California golf course master plans aimed at reducing turf areas and water consumption, by applying classic golf course design principles along with the very high tech concepts of Precision Turf Management (PTM), which we believe is the future for golf courses. Those are intellectually stimulating projects because we are working with a team of world renown experts in related sciences. It’s fun stuff because its leading-edge technology.

We just finished a full remodel of Ottawa Hunt and Golf Club in Ontario, a Willie Park, Jr., original, which is expected to host the 2017 Canadian Women’s Open, a full bunker restoration at Worthington Hills in Columbus and secured three projects of various scopes that have yet to be made public.

But our largest and coolest project is the initial planning for a new 18-27 hole project in a colossal rock quarry. I have been involved with this project for 30 years with various clients, and it is closer now to fruition than ever before. This could be our masterpiece project. Starting with bare rock and creating a world-class golf course through reclamation and creative design techniques. If allowed to reach its potential it will arguably transcend, and I am not exaggerating, such magnificent tracks such Old Works, The Quarry, and StreamSong. I can’t say much about it yet until all the papers and permits are in order, but this is a fabulous opportunity to put together my 60 years of experience in a dramatic, permanent crescendo.