Generally speaking, snow is on the ground by the time December rolls around, but a warmer-than-usual year allows for no snow. This allows me to go visit Earl Bales Park with Lorne Rubenstein, who lives nearby.

Lorne is, at least by my account, in that discussion for ‘greatest living golf writer,’ alongside Michael Bamberger. His book catalogue includes those with George Knudson, David Leadbetter, Nick Price, Tiger Woods and more; plus a book on Moe Norman. Today, Lorne’s writing appears primarily in SCOREGolf, this writer has contributed to Golf Digest, Golf Magazine, Golf World, among others.

As such, any opportunity to spend time with Lorne is a blessing, so the opportunity to walk around the Earl Bales Park is an exciting opportunity for me to not only pick Lorne’s brain, but learn more about this once-great golf course. The park is frequently used by residents of Toronto, including Lorne and his wife, but at one time, it was the location for York Downs Golf & Country Club, C.H. Alison’s lone 18 hole design in Canada.

Harry Colt’s travels in North America were in three trips between 1911 and 1914, while his partner C.H. Alison first came to North America in 1903, but did not begin to build golf on this side of the Atlantic until his trip in September 1920, arriving by boat from Liverpool, England. Alison’s first stop was Grand-Mere in rural Quebec, before making his way through Montreal and to Toronto via train. Arriving in the city, Alison’s visit included renovating Hamilton‘s 13th because Colt’s original par 3 was deemed too difficult, moving the 13th green at Toronto back and as a result, re-arranging the par 3, 14th to its current orientation, and bunkering Weston because Willie Park Jr. returned home to Scotland before he could see the plan through. In 1922, York Downs opened, with Stanley Thompson constructing the golf course on behalf of Alison like he did for Herbert Strong at Lakeview and Devereux Emmet at Beach Grove.

Lorne caddied at York Downs in the 60s as a kid, and remembers it as an upscale, private golf club, though he emphasizes they did not use the word upscale back then: “It was the kind of place that you did not want to step on anyone’s toes, but especially as a kid.” As we walk the once par 4, 1st hole, he reminisces about caddying for $1.50 a loop, and the atmosphere of the caddie yard.

Fifty years after York Downs closed, it can be difficult to assess the quality and magnitude of a golf course closing, but I ask if York Downs closing would be like Beacon Hall closing now—which it might—and he agrees. For context, Beacon Hall is what most, if not all, would describe as an upscale private golf club, and generally ranks in the top 20 golf courses in the country (on Beyond The Contour‘s list, it is 18th in Canada). Alison’s work at both Milwaukee (No. 75) and Davenport (No. 95) are both on Golf Magazine‘s Top 100 in the United States, while my own experiences at Kirtland in Cleveland and Park in Buffalo suggest his skills were of the highest degree.

Alison’s architecture style is not a direct representation of Harry Colt, nor should it be. Instead, Alison’s work seems to be much larger in scale than his partner. Alison loved to build big features: big greens, bunkers, and fairways, with his strategies always making sense. Dogleg right? Bunker the inside corner of the dogleg, and bunker the short right side of the green. His green complexes always matched the size of the features, with big contours, ridges, swales, humps, bumps, hollows: you name it. For Canadians, it is not Stanley Thompson who Doug Carrick’s style most closely falls in line with; it is Alison; though the latter’s greens are far more interesting.

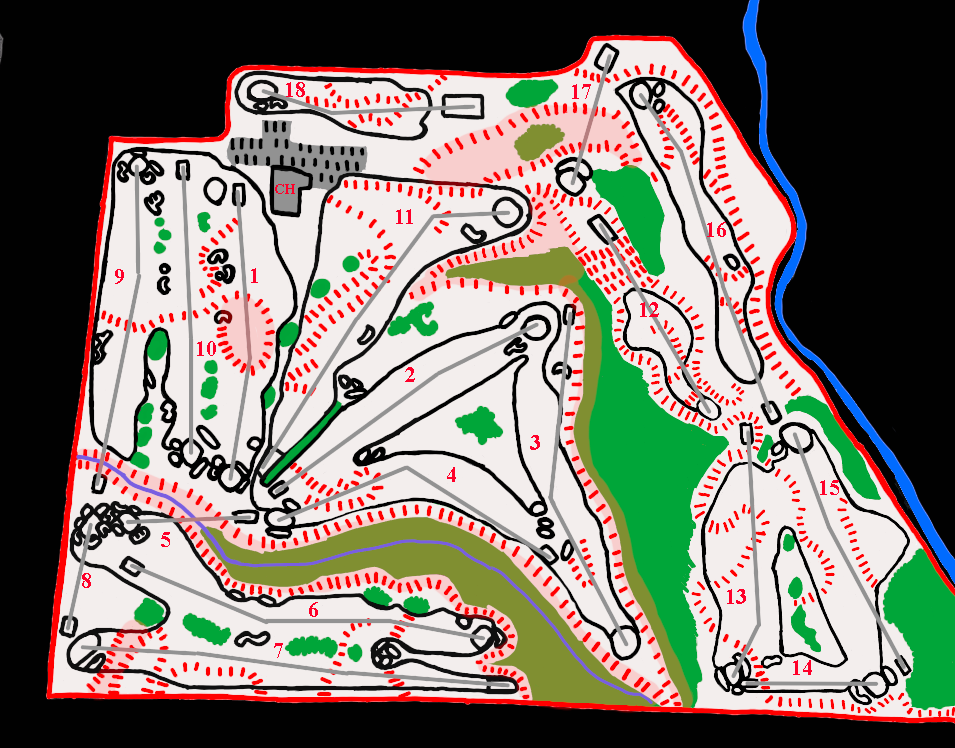

Like his partner, Hugh Alison worked extremely well on borderline too-severe properties. Like Kirtland, York Downs had to find a way to get back down and up the hillside that essentially split the property in half. At Kirtland, the routing plunges into the valley below at the par 4, 10th and climbs up via the par 4, 16th, the par 3, 17th, and with help of an elevator before the tee shot on the closing hole. At York Downs, the 12th drops down dramatically before climbing out on the 17th. Lorne remembers everyone hitting driver on the 255 yard par 3, 12th even if it was dramatically downhill. He recalls it “being the hole everyone looked forward to.” It was that dramatic, and looking through the trees, one can see how severe it was.

Lorne grew up in the area, and if he is not in Dornoch, Scotland or Florida, he often uses the park. He tells stories as we walk to his favourite part of the park, though it was never part of golf. We are looking down at the old par 4, 13th—what seems to a standout hole given the terrain at the bottom of the valley, but Lorne’s corner is a beautiful section of the park at the far south end. From this section, we can see Don Valley, a Howard Watson design that opened in the 50s owned by the City of Toronto.

We never actually end up going into the valley, but it is for the best. The park is preparing to open its ski hill whenever snow falls, and with mud, leaves, and wet grass, it could be a nightmare situation to get down. We jump around the routing: from the 1st to the meeting point of the par 3, 5th and par 3, 8th in the southwest corner of the park where homeless encampments are. We walk down the long par 5, 7th, a 531 yard slog back up the hill over some interesting terrain. To our right, Timberlane Drive borders the park, a so-called wealthy street back in the day (and still to this day). Lorne remembers a girl in his school years who lived on this street and who everybody therefore assumed was part of a wealthy family. “That’s how kids in school thought about anybody who lived on Timberlane,” he says.

After we finish walking back down the long 7th, we walk back down the par 5, 6th and return to the gathering point of the two par 3’s. Even though I know the valley is coming, the holes up top surprise me in the best way possible. On the 4th, for example, the gully, almost canyon like depression hugs the inside corner the entire time. Alison’s architecture is best-suited to angles: on the outside right portion of the green, a bunker awaits those who do not challenge the inside; on the other side of the coin, the left side is straight up the middle to a receptive green.

Numerous examples of such brilliant, simple strategies await the golfer throughout the round, and truthfully, part of the charm of a Hugh Alison. Unlike a Thomas, Mackenzie, or Tillinghast, Alison’s work is simple, yet effective. Such is the case on the par 4, 18th, which Lorne remembers playing past the clubhouse “like Redtail or National Golf Links of America” and behind the clubhouse, separated from the rest of the property (you can view this in the routing plan below). Lorne sees this as an intriguing routing feature, and I agree… not many golf courses in my repertoire come up that have a similar feature. Even with a little uniqueness in the routing, the strategies are Alison’s bread and butter: play to the right and be rewarded with a straight line coming into the green, albeit the land is more severe. From the left, a more difficult angle, coming over two greenside bunkers.

After opening in 1922, York Downs did not make it to 50 years, officially closing in 1971 even if the golf club moved locations in the 50s. Lorne remembers it being a public golf course for a couple of years, and a developer coming in to build houses before resident protests eventually forced the developer to sell the land back to the city to convert it to a public park.

While never the ideal outcome for a golf website, especially when it has such historical pedigree as Charles Hugh Alison, losing York Downs to become a public park is much better than housing, especially when you see it in daily use. On our visit in December, the ski hill is on the precipice of use, people are playing ping pong in the community centre, and the amphitheatre is under construction. People are walking around area like the shared fairway at the 1st/9th/10th, and others visit the hiking trails.

- A 1953 aerial (courtesy of the City of Toronto), with a sketched out routing plan to show the architectural features

Even though the land is put to good use, it is difficult to realize how good the golf course was, and would still be today. The status of Toronto, St. George’s, Hamilton, and more are well-known in Canada… could it be that good today? I can only speculate given what we see on the ground today, what Lorne spoke about, and writings about York Downs. One thing is true, though: it was special, and Earl Bales Park is special in its own regard to this day.

Gallery

Enjoyed reading this today. I joined York Downs as a junior member in 1965 at age 12. I remember every hole, and many angles and shots. Highlights for me was the beautiful condition of the fairways and greens, and the quiet of the lower holes on the back nine. Great golf experience. Paul Trotter