Feature Interview with Lee Pace

March 2013

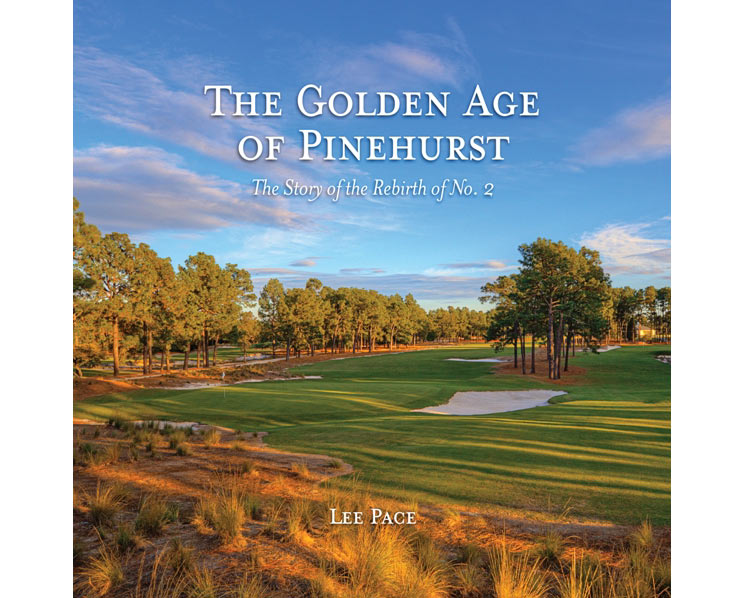

The Golden Age of Pinehurst is Lee Pace’s fourth book documenting the story of Pinehurst. The others were Pinehurst Stories—A Celebration Great Golf and Good Times; the first edition was published in 1991 and a second edition in 1999. The Spirit of Pinehurst followed in 2004. He has written books with former Pinehurst Director of Golf Don Padgett Sr. and LPGA founding member Peggy Kirk Bell. He has also authored the story of Pine Needles and Mid Pines in the 1995 book, Sandhills Classics, which was republished and updated in 2010. Pace wrote and coordinated the production of the Carolinas Golf Association’s centennial book in 2008. He has written about the Sandhills golf scene for twenty-five years for a variety of magazines, including GOLF, Links, Golfweek, Private Clubs, Delta Sky Magazine and US Airways Magazine. Today he writes a monthly golf column for Pine Straw magazine. Pace wrote and edited a coffee-table book for Forsyth Country Club in Winston-Salem. A Century at Forsyth came off the presses in January 2013 to celebrate the club’s centennial. Pace’s passions beyond golf and Pinehurst extend to the University of North Carolina, where he graduated in 1979 with a degree in journalism. He lives today in Chapel Hill and covers the football program through his Extra Points on-line feature and is now in his tenth year as sideline reporter for the Tar Heel Sports Network.

What was the origin for The Golden Age of Pinehurst? This book is another in a series of coffee-table books I have written and produced for Pinehurst dating back to the early 1990s. I started freelancing in 1987 and got to know Pat Corso and Don Padgett Sr. (the key executives at Pinehurst from the late 1980s through the early 2000s) in the course of writing several articles about the new Club Corp regime at Pinehurst and their vision of bringing championship golf back to Pinehurst. Pat was at the Greenbrier in 1990 and found a nice history book on the resort in his room and said, “We need to have one of these for Pinehurst. We need to have a book about Pinehurst, a nice book we can give to the media and USGA and PGA Tour officials and say, ‘This is our story.’” Pat asked if I would be interested in helping them write and produce such a book. Of course, I jumped at the opportunity. I had had some experience editing, designing and producing magazines and coffee-table books, so I knew something about the process beyond just the writing element. I wasn’t sure how a book about Pinehurst should be organized, until early in the process I read about Ben Hogan winning his first PGA Tour event at Pinehurst in 1940, about Jack Nicklaus winning the North and South Amateur in 1959, about local legends like Harvie Ward and Billy Joe Patton winning multiple amateur competitions at Pinehurst. It occurred to me that we should identify a handful of famous golfers who had a story to tell, a landmark experience, a unique perspective about the resort, the village and the No. 2 golf course, then go visit them and write a chapter built around that individual’s experiences. That’s how Pinehurst Stories came about. I visited Hogan, Nicklaus, Ward, Patton, Sam Snead, Arnold Palmer, Bill Campbell, Ben Crenshaw, Curtis Strange, Pete Dye and others to talk about Pinehurst. That was a fascinating experience over about six months from late 1990 to the spring of 1991. I also got three of the finest golf writers in the business to write a piece for this book—Herbert Warren Wind wrote an essay about Richard Tufts, Dick Taylor one about Donald Ross, and Charles Price adapted a couple of earlier GOLF Magazine columns into one piece on the singular nature of the Pinehurst golf experience. Then over the summer of 1991, I sat down at my brand new Macintosh computer with the cute little apple logo on the front and knocked out the design in a program called PageMaker—this in the very early days of desktop publishing. The books were printed in High Point and delivered to Pinehurst at the 11th hour and 59th minute before the TOUR Championship in late October 1991. We updated the book in 1998-99, prior to the U.S. Open coming to No. 2, then in 2004 did an entirely new book called The Spirit of Pinehurst. This new volume included some of the material from the original book, but by now we had remarkable story of that 1999 Open to feature—the success both inside and outside the ropes of the Open’s first visit to Pinehurst. A substantial chapter was devoted to the behind-the-scenes story of how the stars aligned that week and opened the door for Payne Stewart to capture the championship. Looking back 14 years later, it’s incredible how all the dominoes fell that week in Payne’s favor: his warm history with the town dating back to the 1970s, his personal metamorphoses over the 1990s, his coming full circle from using ill-fitted equipment because he was being paid to do so and turning back to clubs he was comfortable with, the confidence he gained by winning at Pebble Beach early in 1999, even his missing the cut at Memphis the week before the Open, allowing him to come to Pinehurst three days early and spend a low-stress weekend studying the golf course and mapping out a game plan. Then, of course, that putt, that 20-footer to win on the last stroke of the championship. A photographer from California named Rob Brown captured the image in a panoramic format the instant the ball fell into the hole—now the iconic “One Moment in Time” photo that will forever define the 1999 Open in my mind. Five years later, the club had exhausted its inventory of The Spirit books, so it was time to do another, particularly with the 2014 Open double-header on the horizon. When I learned in November 2009 that Pinehurst was talking to Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw about a major restoration project on No. 2, I thought that would be the perfect hook around which to build a new book. I talked with Bill and Ben and they were comfortable with having me shadow them during their visits to Pinehurst over 2010 and 2011 as they embarked on the transformation of the course. Any time either of them was in town over the next 18 months, I was there for at least a day. It was a fascinating experience. So that’s how the book evolved: tell the Pinehurst story in the context of the No. 2 course, how it evolved, what happened and what is happening now. So the trilogy of books over more than two decades has included one volume that highlighted the individuals, a second that spotlighted the great competitions, and now a third built around a single golf course.  This is your fourth book on the greater Pinehurst area. Did you learn anything in particular in researching it that was both new and surprising? Since I was born in 1957, grew up in the western part of North Carolina and never visited Pinehurst until my college days in Chapel Hill in the late 1970s, I never saw the No. 2 course in the state that Pinehurst officials and Coore and Crenshaw were trying to revive in their restoration. So listening to Bill Coore talk about how the course looked and played in the 1960s, talking to others who knew the course from the mid 1900s, and studying all of the photos from the Tufts Archives from those days was particularly interesting and illuminating. The two primary tools or guides that Coore & Crenshaw used, beyond their history with the course and their thorough understanding of classic golf architecture, were a set of aerial photos of No. 2 from 1943 and the paths of the original single-row sprinkler system on the course. Bob Farren, the head of Pinehurst’s grounds and maintenance staff, knew from word of mouth handed down over the years that the irrigation lines were in exactly the same places they’d been when Ross and superintendent Frank Maples laid them down in 1923. So Bill and Ben knew that water would have been thrown about 70 feet in both directions—that would have been the areas of the fairways that were watered and maintained. Everything beyond would have been as nature left it. Add those dimensions to the evidence from the aerial photographs, and they had some hard evidence to guide them in ripping out all the Bermuda rough, re-contouring the fairways and re-edging the bunkers back into an unkempt presentation. I remember very clearly the first day that Bill, Ben and their chief on-site designer and construction guy, Toby Cobb, were on-site together. It was in late February 2010. They started the process in one of the far corners of the course, away from the clubhouse, and began on the 11th, 12th and 13th holes. They stood on the 11th tee and Bill talked about how neat and organized the hole looked—straight lines of trees, cart path, rough and fairway. The right side of the fairway did have one of the few strips of wire grass that remained on the course; but even it was tidy and orderly with smooth boundaries. “This is anything BUT what this golf course is supposed to look like,” Bill said. Thus began the process of turning No. 2 from a smooth, green, modern appearance with narrow, straight-line fairways into more of what Donald Ross and Richard Tufts left three-quarters of a century ago. Having spent a considerable amount of time on the subject, what insight can you give us into the personality of Donald Ross? Some say he was warm; otherwise say taciturn. I traveled to Dornoch in 1998 to write a chapter on Ross and the Dornoch experience for the second edition of Pinehurst Stories, and I thought it was time in 2011 for a return trip to further connect Dornoch and the links experience there with what he created at Pinehurst and what Coore & Crenshaw were trying to recapture. I had coffee with several of the old-timers at the club one morning and they talked about how incredibly hard life had to have been in a remote village like Dornoch in the late 1800s. Years later, Ross remembered how stern and dour the leaders in the church and the community had been when he was growing up. Bill Campbell, the great amateur golfer who won four North and South Amateurs at Pinehurst, knows much about his family’s history in Scotland and also knew Ross from his 1940s trips to Pinehurst. “Life wasn’t always easy for the Scots,” Campbell says. “They had a lot of fight in them. They had to. They had to fight for everything.” So I think from this embryo it’s not surprising that a very serious, focused, no-nonsense and principled individual in the person of Donald Ross emerged. He believed the essence of a man was portrayed on the golf course—his principles, his fight, his creativity, his brains, his focus. Ross abhorred gambling on the golf course beyond a small wager. Peter Tufts talked often of Ross’s stern nature. Hugh MacRae of Wilmington, whose family hired Ross for golf courses in Linville and Wilmington, and Marty McKenzie, a lifelong Pinehurst resident, have talked of how dignified and regal Ross looked and how impressive his Scottish brogue was to an American youngster. Ross was a perfectionist and expected those around him to be as well. A man’s word was his bond. Once he scolded his Pinehurst clubmakers for letting the edge of a wood-working tool go blunt; standing before them, he used his considerable carpentry skills to provide a sharpening demonstration. Another time he popped an uppity caddie on the noggin with a five-iron, saying that would be the only “strike” of the day when the caddies were threatening a walk-out over wages. Yet Ross possessed a soft side as well. He loved flowers and gardening—a passion he inherited from his mother—and his daughter, Lillian Ross Pippitt, remembered that he “always brought to the dinner table a choice rose, freshly clipped from his carefully tended rose garden.” Tommie Currie was a club employee and once said: “He was very quiet, a bit stern, dignified. All you had to do was just what you were supposed to do, and you never had any problem with him. There was not a nicer person you’d ever meet. If you were wrong, he’d let you know, and you’d better shape up, and you knew it.” You perused countless photographs for the inclusion in the book. Some like the one from behind the second green on pages 32/33 show a green with wild interior contours. What are your thoughts on how the greens at No.2 have evolved over time? That’s a fascinating issue and one that has spawned quite a bit of discussion over the years. Pete Dye’s opinion that the primary reason the greens have evolved into such a pronounced turtle-back shape is the years and years of top-dressing that have exaggerated their profile. Pete saw and played No. 2 numerous times over the mid 1900s dating back to his days as a soldier stationed at Fort Bragg in World War II. And he’s one of the sharpest and most astute people in golf. So who am I to argue with his opinion? But … If this were the case, why don’t all greens on every golf course from the early 1900s reflect the same convex shape of the greens on No. 2? Why aren’t the greens at Pine Needles or Charlotte Country Club or Forsyth Country Club or any of Ross’s other courses from the 1920s perched up as those on No. 2? Did No. 2 get an entirely different maintenance regimen than every other golf course from that era? I find that hard to believe. If you go to Dornoch, you’ll see many of the greens there in this inverted-saucer configuration. The second hole, the par-three, is more severe than any green on No. 2 in its stark drop-off from the putting surface. You can stand to the side of the second green 10 yards away and the putting surface is above your head. And Ross, by the way, actually designed the first and second holes at Dornoch on a visit from America to his hometown in 1921, but the work wasn’t actually done until 1927-28 because of cost and land access issues. Written verification exists that as early 1907, Dornoch was known for its “plateau greens.” So it is absolutely within reason to believe that the plateau green concept was in Ross’s architectural toolbox when he built the grass greens at Pinehurst in 1935. If you read Ross’s essay published in the championship program for the 1936 PGA Championship at Pinehurst, you’ll find further insight into his concept of the greens and the greens settings. He spoke of the sandy soil and how it allowed him to construct the rolling contours and hollows natural to Scottish links courses and how they provided a unique and interesting challenge to shots that have missed the green. When he dug out those hollows, he had to put the sand somewhere; they didn’t haul dirt away in the mid 1930s like they do today. It only makes sense that he used the material to build up the green profiles. I think it’s very likely that the contours on the interior of some greens have been softened over the years. They pretty much would have to have softened some given that green speeds have increased dramatically. Fifty years ago, golfers were putting on slower Bermuda greens at Pinehurst; today they’re putting on high-tech bent that can be made to roll at 11 to 12 on the Stimpmeter in June. Some of the contours acceptable on Bermuda half a century ago would be unplayable today. The bottom line is that the green concepts are true to Ross’s heritage and original designs. Have years of top dressing exaggerated their profile? Probably so. Tom Doak had a good view on this before the 2005 U.S. Open. Even if the greens have become more severe by accident over many years, so be it. Ross certainly never envisioned the pros hitting 325-yard drives and reaching the greens of the long second and 14th holes with 9-irons. So if the greens add more challenge than they did in 1950, it’s a fair trade off. Ross made his name at Pinehurst. Yet he owned a hotel (the Pine Crest Inn) which competed with the resort hotels and he built courses which competed with the resort. What was the dynamic between Ross and the Tufts? That relationship lasted nearly half a century so obviously it was a strong and healthy one, but it wasn’t without its bumps. Ross could be headstrong and resolute, and there’s no question he clashed at times with the Tufts family. I can point to passages written by Leonard Tufts and then by his son Richard that provide some insight into the ebbs and flows of the relationship. The Tufts Archives in Pinehurst is filled with file boxes of correspondence between Pinehurst officials. You could spend a year just reading what amounted to intra-office memos between the Tufts family and their lieutenants. One year Leonard wrote to Richard about problems in the putting greens and potential causes and solutions. He referenced a meeting with Ross and course superintendent Frank Maples. “I am sorry but as you noticed yesterday, Donald gets mad every time I discuss this subject and Frank, who is glad to work with me, has to do as Donald says,” Tufts wrote. So that shows some friction existed at times between Ross and Tufts, and it looks as if Frank Maples, who was Ross’s long-time course superintendent and construction chief, could get caught in the middle. But Richard Tufts, the leader of the third-generation spawned by Pinehurst founder James W. Tufts, was effusive in every respect in his fondness and respect for Ross. “I don’t believe the world of golf has ever seen a course architect that was his equal,” Tufts said in 1978. “He was a gentleman with the very highest standards, he knew the game of golf very well, loved it and served it to the best of his ability. His career was as a professional, but he was a true amateur at heart. We badly need his spirit in golf today.” What impresses you the most about the work that Coore & Crenshaw carried out at No.2?

This is your fourth book on the greater Pinehurst area. Did you learn anything in particular in researching it that was both new and surprising? Since I was born in 1957, grew up in the western part of North Carolina and never visited Pinehurst until my college days in Chapel Hill in the late 1970s, I never saw the No. 2 course in the state that Pinehurst officials and Coore and Crenshaw were trying to revive in their restoration. So listening to Bill Coore talk about how the course looked and played in the 1960s, talking to others who knew the course from the mid 1900s, and studying all of the photos from the Tufts Archives from those days was particularly interesting and illuminating. The two primary tools or guides that Coore & Crenshaw used, beyond their history with the course and their thorough understanding of classic golf architecture, were a set of aerial photos of No. 2 from 1943 and the paths of the original single-row sprinkler system on the course. Bob Farren, the head of Pinehurst’s grounds and maintenance staff, knew from word of mouth handed down over the years that the irrigation lines were in exactly the same places they’d been when Ross and superintendent Frank Maples laid them down in 1923. So Bill and Ben knew that water would have been thrown about 70 feet in both directions—that would have been the areas of the fairways that were watered and maintained. Everything beyond would have been as nature left it. Add those dimensions to the evidence from the aerial photographs, and they had some hard evidence to guide them in ripping out all the Bermuda rough, re-contouring the fairways and re-edging the bunkers back into an unkempt presentation. I remember very clearly the first day that Bill, Ben and their chief on-site designer and construction guy, Toby Cobb, were on-site together. It was in late February 2010. They started the process in one of the far corners of the course, away from the clubhouse, and began on the 11th, 12th and 13th holes. They stood on the 11th tee and Bill talked about how neat and organized the hole looked—straight lines of trees, cart path, rough and fairway. The right side of the fairway did have one of the few strips of wire grass that remained on the course; but even it was tidy and orderly with smooth boundaries. “This is anything BUT what this golf course is supposed to look like,” Bill said. Thus began the process of turning No. 2 from a smooth, green, modern appearance with narrow, straight-line fairways into more of what Donald Ross and Richard Tufts left three-quarters of a century ago. Having spent a considerable amount of time on the subject, what insight can you give us into the personality of Donald Ross? Some say he was warm; otherwise say taciturn. I traveled to Dornoch in 1998 to write a chapter on Ross and the Dornoch experience for the second edition of Pinehurst Stories, and I thought it was time in 2011 for a return trip to further connect Dornoch and the links experience there with what he created at Pinehurst and what Coore & Crenshaw were trying to recapture. I had coffee with several of the old-timers at the club one morning and they talked about how incredibly hard life had to have been in a remote village like Dornoch in the late 1800s. Years later, Ross remembered how stern and dour the leaders in the church and the community had been when he was growing up. Bill Campbell, the great amateur golfer who won four North and South Amateurs at Pinehurst, knows much about his family’s history in Scotland and also knew Ross from his 1940s trips to Pinehurst. “Life wasn’t always easy for the Scots,” Campbell says. “They had a lot of fight in them. They had to. They had to fight for everything.” So I think from this embryo it’s not surprising that a very serious, focused, no-nonsense and principled individual in the person of Donald Ross emerged. He believed the essence of a man was portrayed on the golf course—his principles, his fight, his creativity, his brains, his focus. Ross abhorred gambling on the golf course beyond a small wager. Peter Tufts talked often of Ross’s stern nature. Hugh MacRae of Wilmington, whose family hired Ross for golf courses in Linville and Wilmington, and Marty McKenzie, a lifelong Pinehurst resident, have talked of how dignified and regal Ross looked and how impressive his Scottish brogue was to an American youngster. Ross was a perfectionist and expected those around him to be as well. A man’s word was his bond. Once he scolded his Pinehurst clubmakers for letting the edge of a wood-working tool go blunt; standing before them, he used his considerable carpentry skills to provide a sharpening demonstration. Another time he popped an uppity caddie on the noggin with a five-iron, saying that would be the only “strike” of the day when the caddies were threatening a walk-out over wages. Yet Ross possessed a soft side as well. He loved flowers and gardening—a passion he inherited from his mother—and his daughter, Lillian Ross Pippitt, remembered that he “always brought to the dinner table a choice rose, freshly clipped from his carefully tended rose garden.” Tommie Currie was a club employee and once said: “He was very quiet, a bit stern, dignified. All you had to do was just what you were supposed to do, and you never had any problem with him. There was not a nicer person you’d ever meet. If you were wrong, he’d let you know, and you’d better shape up, and you knew it.” You perused countless photographs for the inclusion in the book. Some like the one from behind the second green on pages 32/33 show a green with wild interior contours. What are your thoughts on how the greens at No.2 have evolved over time? That’s a fascinating issue and one that has spawned quite a bit of discussion over the years. Pete Dye’s opinion that the primary reason the greens have evolved into such a pronounced turtle-back shape is the years and years of top-dressing that have exaggerated their profile. Pete saw and played No. 2 numerous times over the mid 1900s dating back to his days as a soldier stationed at Fort Bragg in World War II. And he’s one of the sharpest and most astute people in golf. So who am I to argue with his opinion? But … If this were the case, why don’t all greens on every golf course from the early 1900s reflect the same convex shape of the greens on No. 2? Why aren’t the greens at Pine Needles or Charlotte Country Club or Forsyth Country Club or any of Ross’s other courses from the 1920s perched up as those on No. 2? Did No. 2 get an entirely different maintenance regimen than every other golf course from that era? I find that hard to believe. If you go to Dornoch, you’ll see many of the greens there in this inverted-saucer configuration. The second hole, the par-three, is more severe than any green on No. 2 in its stark drop-off from the putting surface. You can stand to the side of the second green 10 yards away and the putting surface is above your head. And Ross, by the way, actually designed the first and second holes at Dornoch on a visit from America to his hometown in 1921, but the work wasn’t actually done until 1927-28 because of cost and land access issues. Written verification exists that as early 1907, Dornoch was known for its “plateau greens.” So it is absolutely within reason to believe that the plateau green concept was in Ross’s architectural toolbox when he built the grass greens at Pinehurst in 1935. If you read Ross’s essay published in the championship program for the 1936 PGA Championship at Pinehurst, you’ll find further insight into his concept of the greens and the greens settings. He spoke of the sandy soil and how it allowed him to construct the rolling contours and hollows natural to Scottish links courses and how they provided a unique and interesting challenge to shots that have missed the green. When he dug out those hollows, he had to put the sand somewhere; they didn’t haul dirt away in the mid 1930s like they do today. It only makes sense that he used the material to build up the green profiles. I think it’s very likely that the contours on the interior of some greens have been softened over the years. They pretty much would have to have softened some given that green speeds have increased dramatically. Fifty years ago, golfers were putting on slower Bermuda greens at Pinehurst; today they’re putting on high-tech bent that can be made to roll at 11 to 12 on the Stimpmeter in June. Some of the contours acceptable on Bermuda half a century ago would be unplayable today. The bottom line is that the green concepts are true to Ross’s heritage and original designs. Have years of top dressing exaggerated their profile? Probably so. Tom Doak had a good view on this before the 2005 U.S. Open. Even if the greens have become more severe by accident over many years, so be it. Ross certainly never envisioned the pros hitting 325-yard drives and reaching the greens of the long second and 14th holes with 9-irons. So if the greens add more challenge than they did in 1950, it’s a fair trade off. Ross made his name at Pinehurst. Yet he owned a hotel (the Pine Crest Inn) which competed with the resort hotels and he built courses which competed with the resort. What was the dynamic between Ross and the Tufts? That relationship lasted nearly half a century so obviously it was a strong and healthy one, but it wasn’t without its bumps. Ross could be headstrong and resolute, and there’s no question he clashed at times with the Tufts family. I can point to passages written by Leonard Tufts and then by his son Richard that provide some insight into the ebbs and flows of the relationship. The Tufts Archives in Pinehurst is filled with file boxes of correspondence between Pinehurst officials. You could spend a year just reading what amounted to intra-office memos between the Tufts family and their lieutenants. One year Leonard wrote to Richard about problems in the putting greens and potential causes and solutions. He referenced a meeting with Ross and course superintendent Frank Maples. “I am sorry but as you noticed yesterday, Donald gets mad every time I discuss this subject and Frank, who is glad to work with me, has to do as Donald says,” Tufts wrote. So that shows some friction existed at times between Ross and Tufts, and it looks as if Frank Maples, who was Ross’s long-time course superintendent and construction chief, could get caught in the middle. But Richard Tufts, the leader of the third-generation spawned by Pinehurst founder James W. Tufts, was effusive in every respect in his fondness and respect for Ross. “I don’t believe the world of golf has ever seen a course architect that was his equal,” Tufts said in 1978. “He was a gentleman with the very highest standards, he knew the game of golf very well, loved it and served it to the best of his ability. His career was as a professional, but he was a true amateur at heart. We badly need his spirit in golf today.” What impresses you the most about the work that Coore & Crenshaw carried out at No.2?

The scale and sweep of the left front bunker at the ninth hole was expertly restored by Coore & Crenshaw in 2010. It once again closely resembles its appearance in Ross’s later years.

I am impressed by the guts that everyone atop the totem pole in this project had to even do it in the first place—from Bob Dedman Jr. and Don Padgett II at Pinehurst to Bill and Ben and on to the USGA hierarchy, who had to support and believe in the concept for it to get off the ground. To strip acres and acres of lush green grass off a golf course? To by design make it look cluttered and wild and even as if it’s not being maintained properly? To pledge to use less water in the maintenance of a world-famous, U.S. Open venue? On the face, all of that sounds crazy. But that’s exactly what they had to do in reverting the course back to the mid and early part of the 20th century. I remember one spring morning in 2010 about two months into the project when Padgett, Coore and Toby Cobb were walking the holes where construction was well underway. They were on the 13th tee, and Coore admired the look of the hillside to the left of the green. Two months earlier, they had talked about turning the water off and beginning to scratch that area up with machinery, to give it the unkempt and natural appearance that would, in time, mark the entire course beyond the fairways. Coore saw that the Bermuda was beginning to die out with no water or fertilization, and he commented on how good it was looking. “People see that, though, and think we don’t have the money to maintain the golf course,” Padgett said. “They don’t understand that’s the look we want. Maybe we should have you and Ben write a white-paper, something we can hand out to members and resort guests, explaining what we’re doing.” Coore & Crenshaw were in and out of town often over 18 months to two years working on the project, but Cobb was living in Pinehurst and was on the golf course every day. I don’t think anyone was rude or incredulous to him, but he got lots of questions from people, “Why are you taking grass off a golf course?” In the end, it took a lot of patience and fortitude from the Pinehurst staff and the C&C team to let the project evolve. They simply had to endure some short-term heat until it was all finished and everyone could understand the concept. What aspect intrigues you the most about No. 2 hosting the biggest tournament for men and women on back to back weeks in 2014? Well, there are two significant elements to the 2014 Opens. One is simply the golf course: How will it play for either Open with no rough and these reclaimed natural sandy waste areas? This would be a fascinating question if only one of the men’s or women’s Opens were being held at Pinehurst. The best thing about this is that it will simply be different. The U.S. Open has for more than half a century been known for its long, demonic rough bordering narrow fairways and every green. There won’t be a single blade of long Bermuda grass on the golf course. The only long grass will be the tufts of wire grass native to the Sandhills area. Mike Davis of the USGA talked frequently upon visits to inspect Coore & Crenshaw’s work of the importance and charm of the concept of luck to the game of golf. This reintroduces luck: What kind of lie will the competitors get when they miss a fairway? And two, of course, is how will this back-to-back presentation be received? The men’s Open will be embraced, certainly. The 2005 Open drew 325,000 spectators over the course of the week, and that’s an accurate number as the USGA scans every ticket holder coming through the gate. That’s a record for an Open. With good weather, you can expect another number in that ballpark for 2014. The two Opens are being sold as one event to corporate hospitality clients, and Reg Jones, the U.S. Open championship director for the USGA, said in February 2013 that sales were ahead of any Open at the year-and-a-half-out juncture since the 2008 economic implosion that damaged the golf industry in so many respect. They had sold all 11 of the top-line packages that include access to the Pinehurst Members’ Clubhouse. So corporate North Carolina appears to be resolute to participate in this two-week event. We’ll have to see how attendance is the second week. Will all the people who took time off from work and family to attend the men’s Open carve out the time and allocate the ticket expense for the second week? Galleries have been huge at Pine Needles over its three runnings of the Women’s Open in 1996, 2001 and 2007. There’s no way to predict if they’ll embrace the 2014 event right on top of the men’s. Gun to head, I think both weeks will be fine. You live in Chapel Hill and are accustomed to the Carolina summers. How do you think No. 2 will hold up for the US Women’s Open after the stress of hosting the men the week prior? I recently wrote an article for the North Carolina Golf Guide to be published this summer looking at Pinehurst and all the plans in the works for the Opens—both inside and outside the ropes. I asked that question of Mike Davis, and he said he doesn’t have any concerns about the course being in championship condition for two straight weeks. The speed of the greens will be the same for both weeks roughly a 12 on the Stimpmeter; the greens will be a bit firmer for the men because, Davis says, he wants all players on well-struck shots from the fairway to get something along the lines of “bounce, bounce, stop” action on shots into the green. Because the women can’t spin the ball as much as the men, the greens need to be a little softer in order to get that same action. He said it’s less problematic to go from firmer greens the first week and soften them up on the second week than vice versa. Bob Farren, Pinehurst’s director of golf course and grounds maintenance, notes that June is the best month for bent grass—the greens are healthy coming out of winter and spring and they’re not yet in the difficult July and August months. He says also that the root structure is the key to being able to maintain firm, fast greens, and he says the greens are in excellent shape two years after being resodded with an A1-A4 mix. There is also the question of landing areas in the fairways and whether the women might find an inordinate number of divots under repair from the previous week. Davis says that the landing areas on most holes will differ from the men to the women, the idea being that to have both sexes hitting seven or eight-irons into a green, for example, the women’s landing area will be closer to the putting surface. “It’s just not that big an issue,” Davis says. “The reality is that playing out of divots is just part of the game. You play the ball as it lies. Sometimes you get a bad break. That’s golf. Dealing with those breaks is part of the examination.” Are you a fan of the idea of reversing the pars and playing the 4th hole as a par 4 and the 5th as a par 5 from its new back tee? The flopping of the pars on four and five is essentially Mike Davis’s idea, and if you absorb the reasoning behind it, I think it makes a lot of sense. First, there is the historical significance of the fifth hole once having been a par-five. In the original configuration of the course reached in 1935 with the addition of the fourth and fifth holes and elimination of two holes that ran between the current 10th and 11th holes, the fifth hole was a par-five and the eighth was a par-four. They were flopped before the 1951 Ryder Cup Matches. When Donald Ross died in 1948, the fifth hole was a par-five. Second, Bill Coore did not like the new tee for the fourth hole that was built in 1996 leading up the 1999 Open. The tee lengthened the hole, but in order to get the additional yardage, it was positioned to the far-right property line (as you look down the fairway) and made for a much straighter hole. You can see the green from that tee if you go out there today. Coore believed that the right-to-left angle was an important part of the hole, and he wanted from the very start in the restoration process to have all tees—member, resort and championship—play along that line. To do that, the tees have to be to the left of the little restroom facility, and you can’t get as much length out of the hole on that angle. So that augers for four playing shorter than it did in 1999 and 2005. Finally, Davis believes the fourth green is one of most sedate on the course, and certainly the fifth green is one of the most severe. He thinks four green is better for a long par-four and five green is better for a par-five. Davis walked around the fifth green on one visit and talked about how he would push the hole locations further to the edge if players where hitting wedge shots into the green as a par-five than he would if they were hitting mid to long-irons as a par-four. So yes, I think the changes are good. The downside is that the fifth hole developed a reputation as one the meanest, nastiest, hardest par-fours in all of championship golf during the last two Opens. Now it will have a completely different character and that historical significance has been lost. I think Don Padgett, the president and COO of the resort and club, made a good point one day on a walk around the course with Davis and the architects. “The bottom line is, you play these two holes together as a par-nine,” he said. And who knows: I wouldn’t put it past Davis, who is known for his “out-of-the-box” thinking in U.S. Open set-ups, to move tees around and play each as a four and as a five during the championship. You have played No. 2 countless times over the past decade. For those who have yet to play No. 2 again since Coore & Crenshaw completed their work, what would you tell them to expect? Like we discussed a few minutes ago about U.S. Opens of 2014, the key thing is that it’s just so much different from what you’ve come to expect at Pinehurst or any other golf course. There is simply no long rough anywhere and the presentation beyond the fairways reflects the ground as Donald Ross found it a century ago—hardpan, assorted “volunteer” weeds, pine needles, organic material. Mike Davis talked frequently on his visits to Pinehurst of his opinion that one of the worst things that’s happened to golf in recent years is how roughs have become much more consistent than years ago. Davis, Coore and Crenshaw all believe that golfers should find perfect tees, fairways and greens. But they believe you should find pot luck everywhere else. Multiple-row irrigation systems and the broad use of fertilizer has allowed superintendents to groom long, thick, consistent rough. Davis made a great point about the conditions that American golfers have come to expect: “Part of the charm and challenge of the game of golf is figuring out what kind of lie you have and what kind of shot you can hit from it,” he said. “Bare lie? In the weeds? Sand under your ball? Figure it out! That’s the joy of the game. It’s very much a United States thing. Golfers here don’t appreciate that element as much. Once you get out of the United States, they get it. Figure it out!” I have found myself on every course I play now envisioning a similar presentation—what would this course look like if they didn’t spend so much time and effort maintain the rough? It might not look as pretty, but it would make for a more interesting game and it would certainly be more natural appearance.

This elevated view down the long two shot eighth highlights the absence of anything linear. Featuring one of No.2’s most famous greens, will a professional meltdown here in 2014 like John Daly did in the 1999 U.S. Open?

You are a strong low handicap golfer. Does No.2 play easier or hardier for you personally since they completed their work? Is there a particular shot or type shot that you are most glad to see re-introduced into No.2’s overall challenge? I don’t have a strong feel for whether it’s easier or harder. If you miss a fairway and have 150 yards to the green and you draw a good lie on the hardpan and have no wire-grass hindrances to your stance or backswing, it’s certainly an easier shot than before when you were hitting from thick Bermuda rough. But if you come to rest on a little layer of that blackish organic material on top of the sand or you’re on a bed of pine needles or you’ve got a patch of wire grass in your way, that’s a tougher shot. And I’ll tell you what is definitely tougher now: a 20-yard shot where you’ve got to use a wedge to fly a bunker and you’re on hardpan. Not a millimeter of error there, and you’ve sure got to hit DOWN on it. What it is, without question, is more interesting. It’s more interesting to look at and it’s more interesting to walk toward your ball if you’re off the fairway in anticipation for what kind of shot you’ve got next. Before, you knew what kind of shot you had—pound it out of the thick stuff. They are working hard to get thatch out of the fairways, and the fact that the maintenance staff is no longer overseeding during the winter will both help to firm up the fairways. That’s another great element—if hit it flush and dead on-line, you’ll get a shorter shot into the green. If you’re a hair off-line, though, the quicker the ball will find trouble. So firmer and faster fairways could be easier at times and harder at others. But again—just very different. What impact will the restoration of No. 2 have on the rest of the area, if any? For instance, Mid Pines is in the midst of an impressive effort to re-establish its own sandy playing characteristics. One of the more interesting people I met in following the restoration of No. 2 was Kyle Franz, the young guy on the Coore & Crenshaw team who spent a number of months in Pinehurst working the machinery and the rakes and hoes. He’s very bright and is absolutely nuts about golf architecture and construction. He spent some of his spare time scouting out the other Donald Ross courses in the area, and, understandably, was attracted to Mid Pines, which of course is one of the purest Ross courses anywhere. Kelly Miller and Pat McGowan, members of the ownership family at Pine Needles and Mid Pines, and Dave Fruchte, the course superintendent, had been thinking for some time of re-doing the Mid Pines greens, which had become quite bumpy over the years with the infiltration of poa annua. Kyle, meanwhile, thought the course would look great if they went in and took out some of the rough, rebuilt the bunkers to reflect the more ragged look of the early 1900s and restored some architectural features that had been lost over the years. They all put their heads together and came up with a plan that they began implementing in the fall of 2012 and will continue through the summer of 2013. The result will be new Mini-Verde greens, a few new tees, re-contoured fairways and the reinstallation of some of the sandy waste areas outside the fairways. I think Mid Pines with this retro look and great new greens will be one of the great stories in resort golf in 2013. Another key element of the No. 2 restoration and the buildup to 2014 was the fact that, beginning with the winter of 2010-11, Pinehurst quit overseeding the fairways with rye grass. That has long been a sticky wicket—the travelers from New York want to see bright green when they come down in January and February and early March. But that rye retards the emergence of healthy Bermuda in the spring and the thatch left behind when it dies out builds up and is the antithesis to grooming a firm, fast playing surface. Bob Farren found a course at the coast that was using a particular dye or colorant that gave the ground a faint green look—nothing artificial like some dyes you’ve seen that wipe off on your shoes and golf ball. So for the last three winters, Pinehurst has used that product and gotten a bit of the color that the resort guests want but haven’t had to overseed. The process has worked so well they’ve started to use it on some of the other courses at Pinehurst. So you could see more and more of an avoidance of overseeding during the winter, which is purely a cosmetic thing and does nothing to improve the playing characteristics of a course. There are many, many stories and great quotations sprinkled throughout the book. Do you have a particular favorite that best captures the essence of the place? One of the fun things in putting together The Golden Age of Pinehurst was collecting quotes from the classic architects that applied not specifically to Pinehurst but to the early days of golf design and overlaying them on photos from No. 2—either archival black and whites from the Tufts Archives or current images taken upon completion of the restoration. One of my favorites is the comment from Alister MacKenzie: “Narrow fairways bordered by long grass make bad golfers. They do so by destroying the harmony and continuity of the game and in causing a stilted and a cramped style, destroying all freedom of play.” The first sentence of that quote is overprinted on a two-page spread photo showing a golfer hitting his tee shot on the fifth hole in the 1950s. You can see the incredibly wide fairways that afforded the golfer the ability to aim to the left to cut the length of the hole (but also risk having his ball bound further left into the trees) or play safely to the right, adding an extra club or two onto the approach shot. You can also see that there is no long grass anywhere, other than the clumps of wire grass to the sides of the fairways. It’s a great look and one of the templates to the kind of appearance Coore & Crenshaw were working toward in their restoration. At one time Pinehurst was the preeminent golfing resort in the United States. The U.S. Opens and the restoration of No. 2 have restored a considerable amount of luster. Along with the addition of Coore and Crenshaw’s No. 9 Course, what else do you think would help bring the resort back to that high water mark? Well, No. 9 is way down the road. There was some thought by Bob Dedman in late 2011 and early 2012 to pulling the trigger and having the course done in time for the 2014 Opens. I think his heart was saying, “Do it.” It would have been a fun project and would have generated a lot of buzz in the golf world. But his brain ultimately won over. He simply couldn’t justify the expense that a new course would have required in what is still a soft golf economy. Pinehurst’s niche as America’s most historic and pure golf destination is secure. The resort and club have stable ownership; Dedman is committed to the future, and the fact he’s buying the Fownes house in the Village is further testament to his long-term priorities in Pinehurst. I think the attention No. 2 will get in and around the 2014 double-header will be terrific and will further open the public eye to the idea that a golf course needn’t be groomed to perfection on every square inch of the property. That might be feasible at Augusta National, which has limited play and unlimited resources, but it makes no sense for the rest of the game. I will quibble with your question a little bit in that it seems to assert that Pinehurst no longer has the “eminence” it once had. There are any number of standards to judge a golf destination by, and thus you can come up with a handful of legitimate “No. 1s” …. depending on your yardstick. But Pinehurst has something that no other golf destination in the country can match—history, tradition and an umbilical cord to the early days of golf in this country and, in fact, to beginnings of the game in Scotland. I don’t see that ever changing.

THE END