1. How did you get started in golf course architecture?

I wanted to combine my love for the game with my military map reading and terrain analysis skills learned early in my Army career. In college at the University of Richmond, I started the Orienteering team which was nationally ranked. I was high in my class (Field Artillery Officer Basic) in terrain identification, target acquisition, range estimation and firing.

Once I returned to Richmond I started trying to find a way into the business. A friend introduced me to Algie Pulley who was born and raised in Petersburg and had some projects in Virginia. I basically went to work nights and weekends doing anything Algie needed. Looking at sites (not sure I was qualified to do anything at this point), chasing clients, following up with loose ends that Algie always left behind from his visits, printing plans etc. Algie was an extremely gifted map reader and civil engineer. Early on, I think the only things he saw in me were determination, leadership skills and an equal ability in terrain reading. He still taught me the basics and I spent almost 4 years working for him. I was under the tutelage of his Senior Designer, Tom Self. Tom taught me everything. He is one of the best designers of whom no one has ever heard. Tom was very artistic and spent two years in Richmond teaching me routing, grading, drainage, plan development, rendering and much more. Tom also taught me life outside the military, which was no small task considering my father was a 34 year veteran of the Air Force, so that’s really the only kind of structure I knew.

Once the S&L crisis and the resulting RTC takeover hit the economy, I was forced to go into business for myself. I opened my firm (Colonial Golf Design) in late 1989 with a balance of $156 in my checking account.

2. During normal economic times, how hard is it seeking work under your own name given that you haven’t won a major?

I established my firm to provide quality golf course renovation and restoration services to the region because I saw the need and felt that no one was doing high quality work in my area. Of course it took time to establish my name recognition but I got some early breaks that put my name out into the industry.

By 1995, I was starting to become known regionally and it was becoming easier to get into doors I couldn’t get onto before. After finishing The Colonial Golf Course in Williamsburg Virginia which received “best new” status in several publications, and the Sundance Golf Course in New Braunfels, Texas which won awards as well, I was off to Ocean City, Maryland to do my first resort course at Ocean City Golf and Yacht Club.

That was my first total renovation project and it turned out well. The folks at OCG&YC really trusted me to deliver and I worked hard not to disappoint them. What a great site it is as well. Soon after, projects like James River Country Club, Elizabeth Manor, The Country Club of Virginia, Princess Anne Country Club and Country Club of Petersburg came calling. For the next 13 years I stayed busy and selling my “name” had me handling as many as 10 projects per year.

I did entertain going to work for Ed Seay at Palmer Golf Design at one time very early in my career. I guess after my apprenticeship I just felt like I wanted my name on the plans, not someone else’s and Ed reinforced that for me years later as I became a member of the ASGCA. He said, “Best decision you ever made” when I reminded him of it a few years ago.

3. How was working with Vinny Giles at Kinloch? What did he add to the project?

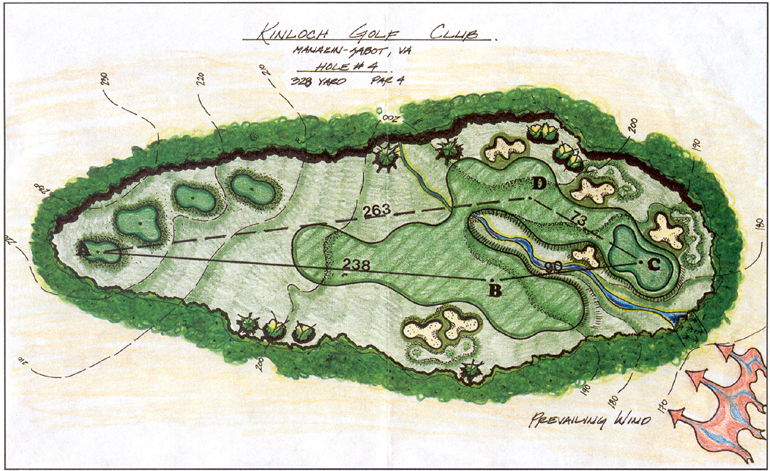

Working with Vinny was great. I had only known Vinny for about 7 years when he called me in the late summer of 1995 and asked me if I would help him with a project with which he was thinking of being involved. Vinny had helped me get in some doors by then and I guess he felt comfortable with my ability. By the fall of 1995 I had completed the routing for what would become Kinloch Golf Club. 200 acres of woodland just west of Richmond that was originally slated to become a high-end daily-fee golf course. After we got the routing set, we cut centerlines and walked the site for a few months. I made ONE change to the routing and we were set.

Vinny added a great deal of credibility to the project and I could always count on him to be a liaison with the developer and work for the architecture interests of the project. Vinny initially came up with the idea for a private golf club with a strong local membership augmented by a select group of national members unlike anything in the region with “tournament playing conditions” provided every day. We spent months comparing notes and discussing the great courses of the world and the things that made them great. We talked about bunkers, greens, fairway orientation, width and contours. I really focused on what he was saying about the things he thought were good and the things he thought were not so good. He had a very loud voice about what he thought was wrong with “modern” architecture and kept the focus on the more traditional “golden age” courses and architects he thought we should study.

Keep in mind that Vinny Giles is the ONLY player to ever win the US Amateur, British Amateur, and US Senior Amateur Championships. He also recently won the senior division of the British Senior Amateur at Royal Portrush. Needless to say, I gave him a lot of voice because of his incredible playing perspective and experience. The nice thing about working with Vinny was that the more consideration I gave him, the more he told me to “design the best course the land could give”. He actually admitted that he knew nothing about the mechanics of design or construction (I think he was being humble) and that it was my responsibility to guide him and the team through the process. He didn’t want to override my experience just to push and agenda. Naturally, the more he backed off, the more I wanted him involved. The more he insisted that it was my design, the more I wanted his input.

As seen from this aerial behind the green, the fourth hole turned out as George and Giles intended.

I had always hoped that if I ever got to collaborate with a great player that it would be a true collaboration and not just an exercise in ego. We spent hundreds if not thousands of hours on the course together. Once things were rough shaped we would look at them and discuss them. In the two years of construction of Kinloch, Vinny and I never had a contentious moment. Even if we saw something we didn’t like, we would discuss it, make a decision and act on that decision. I did not compromise on my design, nor did he challenge me to. In return, I listened to his opinions and his basis for his concerns and came up with a solution he could endorse. For example, I had drawn the tenth green as cut-to-balance type green that was directly into the hillside and would have resulted in an uphill shot (10 to 15 feet above the fairway) and a partially blind second shot depending on your position in the fairway. My rationale was to move very little dirt and keep the walk to the eleventh tee close. I knew the moment we approached the landing area that Vinny did not feel the same passion for that type of green as I did. At first I thought he was going to give me the “I don’t like blind shots” routine and we were going to debate the merits of the hundred or so great holes that have semi-blind approaches. Instead, and to his credit, Vinny simply reminded me that we had a semi-blind approach on number six and another on number nine. He asked “do we really need another here”? Then he said, “Is there any way we could lower the green, tie it into the nice swale at the toe of the hill and make it look like it “melted” naturally out of the hillside”? Right there we had the connection I was hoping for. Not only could we do it, we were convinced we were going to do it!

We approached the rest of the project that way and it was a lot of fun and very gratifying for me. Recently one of the golf publications included the work we did at Kinloch with Vinny as one of the greatest collaborations of all time. To be mentioned in that group was very flattering to both of us.

4. Let’s take a look at the aerial below from behind the second green at Kinloch. Walk us through what you like about the finished hole.

The 2nd at Kinloch Golf Club is a simple “risk/reward” hole that just happened to have the exact landform I was looking for to create an early strategy hole in the round. The left side of the fairway is obviously the harder side to access based on the cross bunkering. It is narrower and the elevation is higher. If a player elects to carry the cross bunkers and is successful, the reward of a much better angle to the green, coupled with a higher elevation (sight line) is gained. The wider fairway on the right allows for less risk on the drive, but is complicated with a slightly uphill, and depending on your elevation, a possibly semi-blind shot into the green. The 2nd at Kinloch represents “golf-architecture 101” where, given this landform, I am sure most architects would have considered this type of hole. It is a lot of fun to play and I play it differently each time. Many things factor into the way I approach the 2nd including the tee I am on, the wind, the hole location, and the way I am playing. I usually go left, I seldom make birdie. That is not and indication of design, just an indication of my lack of ability to score!

5. Tell us about Kanawha. What was the vision and purpose behind the founding of this nine hole course/club?

Kanawha Club was created for a special client who is “practice-aholic” and wanted to build a nine hole par three golf course for family, friends and special invitation members only. When he approached me about the project he was detailed and precise about the kinds of holes, distances and difficulty he wanted. I was charged with filling in the blanks regarding design, construction, maintenance aspects and “the look”.

This client is a member of numerous clubs around the country as well as Kinloch Golf Club. He already had a short game practice facility behind his home in Richmond. He purchased about 85 acres west of town adjacent to the James River. Early on in the process of zoning it was determined that the club would be private and never have more than 100 members. The vision was clear, develop a “world-class” par three course with extraordinary holes and condition them at an extremely high level. We spent quite a bit of time going over routings and concepts before we went before the zoning bodies. Once the nine holes, range and irrigation source were set, we went to design. The course was built by Landscapes Unlimited of Lincoln Nebraska (they also built Kinloch). The clubhouse, which is simply elegant and elegantly simple, was designed by a local architect and the owner’s wife and for one purpose—comfort.

Not unlike the 16th at Augusta National, the sixth at Kanawha features a green with a fierce right to left tilt. As the golfer shys away from the water hazard, his next shot likely becomes progressively more difficult.

6. Did the fact that play would average ~ twenty rounds a day in any way influence your design at Kanawha?

Yes it did, it was a huge influence. Limited play, very few carts, no cart paths and the challenge from the owner that he wanted interesting greens with some penalty built in allowed me build holes and greens with bolder contours.

Early in the process, the owner and I spent a lot of time discussing realistic green speeds and the types of grasses and maintenance levels they require. The greens were designed with a maximum green speed of 9.0 to 9.5 in mind. Unfortunately, over time the green speeds have been allowed to creep up to 12.0 or higher which, in my opinion has made many pin placements unattainable. Eventually, rather than slow down the greens, the owner has asked me to reduce the amount of slope in two of his greens.

The lesson learned from that as an architect is to better DEMONSTRATE to the owner the effect of green speed and slope and how it can influence play. Even in a case where the owner was a member of about 10 different clubs, I should have done a better job in making sure he wanted bolder contours. I should have anticipated the green speeds would go up (as they often do) that would have allowed the owner to understand the consequences of slope and green speed on his golf course.

All-in-all though, Kanawha Club is a lot of fun to play and requires the player to have some mastery of his short game to score well, which was the owner’s initial set of objectives.

7. High humidity and high evening temperatures make Richmond, Virginia a nightmare for growing grasses good for golf. Yet, the greens at Kanawha are as good as any in the country. Minimal traffic certainly helps but what grass scheme did you go with there that works so well, even in those weather conditions?

Kanawha Club is the only course in the area with unblended A-4 bent grass on the greens. We had success with blending A-1 and A-4 on other courses in the area but because of the anticipation of low traffic, and in consultation with the USGA and the course superintendent, we experimented with the A-4 and have been very happy with the results. We used Tif-Sport Bermuda grass on the fairways and surrounds because of its low mowing capabilities and its drought and disease tolerance. In the primary rough we used a cool season blend of turf type fescue and bluegrass that we had success with at Kinloch. In the out of play areas (outer roughs, wood lines and open areas between the holes), we went with fine fescues to create a distinct texture difference and dramatic contrast in height.

The greens at Kanawha Club do hold up against most in the country primarily because of less traffic, hand mowing, and extreme care by Paul Van Buren the golf course superintendent who came over from Kinloch Golf Club.

8. Describe your impressions when you toured the property at Ballyhack for the first time.

The first time I ever saw the site for Ballyhack Golf Club was from a car going 40 miles per hour! The guy I was riding with said, “I want to show you something interesting”, so we went out there. My very first thought was how 370 acres of land that extraordinary could be so close to the city limit (2 miles from the Roanoke City line) and not be scheduled for some development. More importantly, “What are we waiting for?!” One reason was permitting.

I quickly learned that even if one could acquire the property, the chance of development (for anything) was remote. Why? Because the land resided within the Blue Ridge Parkway “view easement” which was federally protected. The site had also had been considered for a landfill, sewage treatment facility, and, the day I first saw it, it had a new portion of Interstate Highway planned to go right through it!

Little did I know at the time, that a number of people had tried to purchase that farm and all offers had been rejected. “You’ll never buy that farm in your lifetime”, my friend said, “We have already tried”. I was completely amazed at the terrain, the scale, the 200+ acres of grassland and the opportunity to do something outside of my design palette. I was mesmerized by the place. It would be a couple of years before I stumbled upon a way to get it on the property and actually walk it. Once I did, I was haunted by it. I literally could not stop thinking what could be done with this site. It took me a couple of more years to get it under control and get it zoned for a golf club.

9. The end result is an extremely bold design with wide fairways, deep bunkers (some of which are in the middle of fairways) and greens with four foot plus of contour. How did you formulate a vision for such a grand course?

Time on site was the best thing that happened. Once I got the land under contract I had a long time to study the unique characteristics and terrain on the site. It’s an overpowering site with incredible vistas and differing horizons I just kept returning to the theme of maximizing the most dominating terrain forms. Since the road bisected the site (which I thought was one of the greatest opportunities for the routing to be unique) I had to spend a lot of time making sure that if I ended up with a balance of 9 holes on each side (which I gravitated to over time) that each side had to be unique to itself while mating well with the other. So anything less than a big, wide, open course would have seemed terribly out of place to me.

The second hole at Ballyhack features a fairway in excess of seventy yards in width that is peppered with deep, menacing central hazards.

The vision for the course kept coming back to a few different themes like scale, size (of property and course) vegetation and the fact that the site had so many tremendous vantage points and vistas in so many directions. From an operational or business standpoint, I was sure that another private club was not the answer for this area. I just couldn’t look into the future and justify ruining this unique site with a lot of pools, parking, tennis and other such amenities. I really wanted to do something like the destination clubs that had been developed out west like Sand Hills and Sutton Bay. From an architecture standpoint, I started looking at the natural beauty of all of the fescue and orchard grasses that were already present and began thinking “links”. That led me to start eliminating certain areas of the site because of trees, access and continuity. I really started to avoid the wooded areas.

Even though some of these areas would have yielded very good holes, once you got there, you couldn’t get back to great holes without compromise. So, by process of elimination, I started centering on access, continuity, relief, separation, variety and drama. Each of these things directed a series of processes that concentrated the golf course toward the center of the land. The lower ground that today is occupied by the practice facility, 3rd, 6th, 7th, 8th 13th, 14th and 18th, started to stand out in almost every routing. The two major ridges that became instrumental in the front nine on the 2nd, 4th, 5th, and 9th and the high ground associated with the 10th, 11th, 12th, 15th, and 17th could only be used together but a number of ways without having to create long distances between holes and wasted space.

I determined early on that there would be no residential development “in” the course so continuity and flow was a big factor in routing. I also wanted to move as little dirt as possible, not just from an efficiency point of view, but because I just didn’t want to corrupt the beauty of the site with a bunch of earthmoving. I was fairly convinced that I would never get another mountain site with so many unique features and I didn’t want to mess it up.

10. Ballyhack essentially requires a cart to get around. Explain what would have been sacrificed if you remained hell bent in making it a walking friendly course.

I knew the first day I walked the site (man was I tired after that) that the probability of a “walking friendly” golf course was probably out of the question. The site has about 200 feet of elevation change form lowest the point (near the 8th green) to a high point near the 15th tee. Most importantly, the site is only 370 acres. That is a fairly high frequency of elevation over a site that size. There are very few areas of “flat”, and most of those were associated to the road running through the property. Even though I spent a great deal of time thinking “out-of-the-box” to place the clubhouse, parking and cottages, the site of the existing farm house and location of the barns was the most logical and best use of those areas. It seems the people who originally settled on this site over 200 years ago knew something about structure placement too.

Many of my routings concentrated on using the boldest features on the site. Sometimes the holes were placed right on the features (ridges, spurs, promontories, saddles and hilltops) to create the drama and scale that I wanted. Examples of this include holes like the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 9th, 11th, 12th, 16th, and 17th where the feature is used as a foundation for the hole. Once you commit to using the boldest features you must then concentrate the other holes to work harmoniously with the rest of the routing. Holes like the 3rd, 4ht, 7th, 8th, 10th, 13th, 15th, 16th, an 18th play along the sides or between other features using the terrain as support or transition from one feature or another. If a “walking friendly” course was the priority, the routing would not have allowed the trek from the 4th green to the 5th tee or the 8th green to the 9th tee. A walking golf course at Ballyhack would have most likely eliminated holes like the 1st, 5th, 11th, 15th, and 17th. I could not imagine Ballyhack without those holes! The bottom line was that I was determined to violate a few “rules-of-thumb” of routing to insure the course got the best holes.

11. As at Kinloch, Ballyhack features multi-option holes, highlighted by the second, sixth, eighth, and fifteenth holes. Where/how did you develop an appreciation for such holes?

Early in my career I studied the golf courses of the master designers and quickly found an appreciation for multiple teeing options, landing areas and approaches to greens. I was not only intrigued by the design of such holes, I felt it was a part of the game that had been vanishing during the modern age of architecture. I worked hard to understand the holes that were considered great and I found that many of them had the multi-option characteristics. This was also one of things that Algie Pulley stressed in his designs. He always had drivable par fours, multiple route options on par 5’s and varying strategies regarding approaches to greens. I think this influenced me to look for these opportunities in all of my routings and designs.

Once I played the courses in Scotland, especially The Old Course, I was convinced that the way to create interest, enjoyment, strategy and intrigue was to build these options into as many holes as practical.

Looking back up the 15th at Ballyhack, one gains an appreciation for the vast array of playing angles.

12. Tell us about the transformation of The Old White at the Greenbrier whereby you oversaw the return of nearly all of Seth Raynor and CB Macdonald’s features. What was the course like pre and post work?

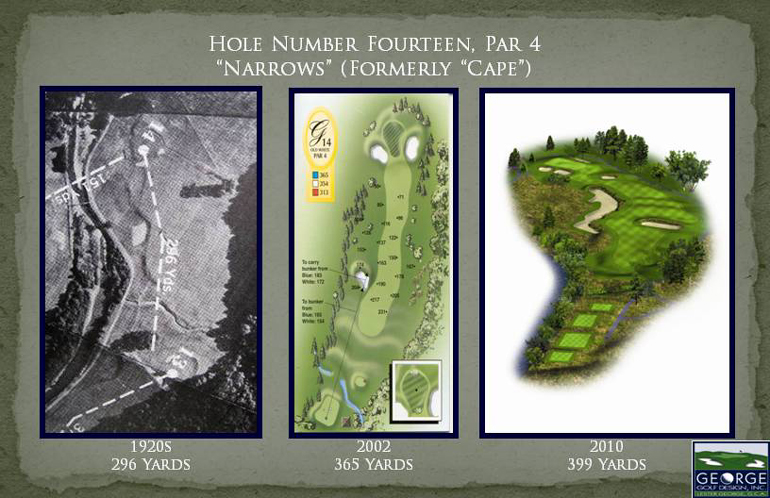

When I arrived at The Greenbrier in 2002 to start the restoration of the famed Old White Course the original course was all but lost. About 75% of the routing was still intact but hardly any of the original Macdonald/Raynor features were there. There was no Punchbowl, no Plateau, no Biarritz, no Alps, and no Narrows. More importantly, these wonderful examples of the famous template holes were reduced to round greens, oval bunkers and over planting of trees between fairways where option routes once existed. Over the years, especially the post-depression and war years, the course had been reduced to a hardly working model of its original self.

Original Macdonald/Raynor bunkers had been filled in. Other features such as the high mound associated with the Alps hole (13th) and the mounds left of the fifth green were gone. Important hazards such as the streams on the 5th and 12th were filled in. Most of the fairway bunkers had been removed.

Robert Harris the Director of Golf and I saw a chance to restore (not renovate) one of Americas classic golf courses and saw pretty much eye-to-eye on how important that would be to the Greenbrier Resort. We convinced the Board of the Hotel (then owned by CSX) that restoration would be the best thing to do for them and the patrons of the resort. Over the next 4 years we labored intensively to re-create the course to as close to the original as we could. We used old aerial photographs as our guide. By studying the length of the shadows associated with the lost features we could determine their height and approximate location from the original design. In many cases (not all) we chose to adjust these hazards to a relative position on the restored course to influence today’s play. Eventually we got back as many of the characteristics of the original work of Macdonald and Raynor as was practical. The restoration was completed in 2006 a full two years before the resort was sold.

What a treat to once again play a full length Biarritz green at The Old White!

13. What are some examples of work that you undertook to insure that Raynor and Macdonald’s strategic features would hold up well against players that drive it 320 plus yards and hit 7 irons nearly 200 yards?

There was no way of knowing in 2002 that a professional event would be played on the course in the future. However, the West Virginia Amateur Championship, a very prestigious event was annually contested on the Old White. That event gave me a chance to observe the best players in the state play every year on the course. Since it took four years to complete, I got a chance to observe and adjust my design as we went. This allowed me to incorporate more demand and precise shot values into the design. It was a “work-in-progress’ restoration with “real time” feedback built right in. That allowed me to create such features as the false side of the green on the 2nd hole and the false front on the 14th green. It also allowed me to re-introduce the fine fescues in the roughs on holes like the 3rd, 14th, 16th, and the 17th. It allowed me to re-create the famous “horseshoe” contour in the 18th green as well. We also removed about 3,000 trees which allowed for wider corridors and more options to approach the greens, a common Macdonald/Raynor theme on the original course. I got to re-instate nearly all of the lost fairway bunkers which put a greater premium on driving the ball.

Most importantly we were allowed to recreate the putting surfaces as we saw fit within the guidance of the original Macdonald/Raynor framework. That means we could do things like the re-create the Plateau green on the 7th with three distinct tiers (on at ground level) and re-create the stream flowing through the 12th fairway which dictates the angle and length of the second shot.

All of these things were important to make the restoration credible in my mind. I also was challenged with expanding the teeing grounds to accommodate the patrons and guests of the hotel so the course would remain challenging and fun for them as well. I feel we accomplished both goals since the popularity and profitability of the Old White has been restored as well.

14. Having also worked at Cavalier Golf and Yacht, where do you think the work of Macdonald, Raynor, and Banks ranks among the Golden Age architects?

I place the work of Macdonald, Raynor and Banks very high among the Golden Age architects. It is important to note that Macdonald was the first to proliferate the template style around the country based on his belief that there could be no better holes created than the ones he thought were the best in Scotland. This limiting philosophy forced Raynor (and later Banks) to be creative enough to craft reasonable facsimiles of those holes into differing sites. It was, in my opinion, the genius of Raynor that actually made Macdonald successful and accepted in his philosophy of re-creating the great holes. Imagine the vision that Raynor had to have to arrive on completely different sites around the country and try to mastermind the same 25 holes into each routing he completed. Most might think that would be simple, I disagree. That would be extremely difficult to do in light of terrain, vegetation, drainage, and soils.

It has recently been documented that Macdonald may have never visited the Greenbrier’s Old White until after it was completed! Can you imagine the trust and confidence that Macdonald would have had in Raynor to just approve his plans without ever seeing the site?

These guys were also very in tune with the same types of strategy found in the courses in Scotland. To transfer that understanding, interest and challenge from the old country to the fledgling American market means they have to rank very high, if not first in my book.

15. You have exciting plans drawn up for a practice area/course for a private club in North Carolina. What are some of its key differentiators that will help make it fun to practice?

First and foremost, flexibility. The site is 70 acres and allows for a double-ended range complete with a short game practice area that allows every conceivable shot in golf (i.e. where the ball is above or below your feet, etc.). There are very few trees which allows for less canalization and more ways to utilize the wind. The most exciting part is the 10 hole practice course which is not only reversible (clockwise it plays to a par of 37 and counter clockwise it plays to a par of 36) but it has options to be played with 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9 hole loops within it self. It utilizes the terrain to take advantage of elevation, wind, light and shadows, and strategy. I think it will be more fun because it will allow a person (or group of people) to go out and complete nine holes in less than two hours and experience every shot in the game. I have designed over 20 practice facilities and this one has it all.

16. How do you feel about golf course rankings? Are magazine ratings good for your profession? Who should serve on such panels? Is there any accounting for the tastes of raters?

Good question. I am sure I don’t have an answer, but I will give some of my thoughts on the matter. I think they are a necessary part of the industry just as entertainment, art, architecture and almost any other creative field of endeavor are rated, ranked or evaluated.

It should, by my definition, be a solely objective endeavor, but that is next to impossible. The more you try to apply static design tenets and objectivity to the dynamic practice of golf course design you have problems. Imagine if there were yearly rankings during Donald Ross’ tenure at Pinehurst. The raters would have had to evaluate his #2 course every year for decades! If, given my definition of objectivity, you ask, “Is there any accounting for the tastes of raters”, I think not. Course rankings will always differ because the people evaluating them are different. It’s why we have 33 flavors of ice cream and choices in automobiles, clothes, restaurants and homes. People have different tastes, and should. There is too much emotion involved (rightfully so I think) to remain objective when trying to evaluate something that is designed to give pleasure to the participant. I really think it is a near impossible task and I am not sure anyone can police the “rules” of ranking strictly enough to maintain objectivity.

Modern rankings were created by the major golf publications to sell subscriptions or advertising, and therefore have a financial motive. Rankings are definitely a double-edged sword with regards to whether or not they are good for the profession. On one hand they generate debate and discussion which naturally crosses over into recognition for the architect, course, developer or owner. Unfortunately, if the debate and discussion is negative, the recognition still follows. I have had the benefit of both. I was once asked to rank courses for a publication and refused because it just did not matter to me to give my opinion. I was sure it did not matter to anyone else either!

Every architect can point to instances where their course was unfavorably looked upon by a rater who may have encountered poor conditioning, bad weather, poor hospitality, over crowdedness or whatever. Conversely, some architects enjoy high praise for every course they create, even if the course is marginal. I listened to a debate between two well known architects one day about a very famous course that had slipped in the rankings. One contended that the reason the course dropped in the rankings was access, the other argued conditioning! Neither of them mentioned the course as is stood among the others in the rankings! So if architects can’t even focus on the salient aspects of rankings how do we expect anyone (or group) to get it right? On another occasion I listened to a person describe an architecturally splendid course as “terrible” because the greens were slow that day. Go figure.

I just think it is impossible to have a definitive list of “best” anything. I do think it is good for discussion on Golf Club Atlas because of what it reveals (consciously or sub-consciously) about all of us.

Featuring numerous decisions that need to made on the tee, Kinloch has been a darling with raters since opening in 2000.

17. What changes do you see in the future of golf course design and construction based on the new economic world order? For instance, Ballyhack is a private club in a remote location. Will such clubs/courses continue to be built?

I am no better at reading the crystal ball than anyone else but I do think we are in for some changes. First, golf courses have become too complex, too expensive to build and too expensive to maintain. Some of this can be attributed to the competition among developers, owners and clubs for overindulging and trying to create their own version of “perfection”. I call this the “Television Syndrome”. The “Television Syndrome” is the practice of trying to make your golf course, regardless of its foundation, purpose, niche or patrons, look like what someone saw (and liked) on television. If you took a concentrated look at all of the golf courses that have gone out of business since 2008, you would find the majority of them tried to fulfill some unreal need to be something they weren’t.

I think architects, builders, superintendents, players, developers, land owners, members and operators all had a hand in this development. I don’t think in most cases that there was anything sinister going on, I just think we all ought to do a better job educating the people we work for in the things that matter. What matters? For me it’s designing golf courses that are fun, challenging, efficient, attractive and sustainable (financially and environmentally).

I am concentrating on courses that I hope will attract new players to the game and make golf more interesting to existing players. I think the future for courses like Ballyhack, Sand Hills, Sutton Bay (national destination private model) and others remains positive as long as we don’t fall into the same pattern of “one-upsmanship” and over saturation. The demand is there for a these types of clubs as long as the development cost are kept to a minimum (implying a certain type of design) so that national members can enjoy the benefits of a unique facility at a reasonable cost to join and visit with their friends, family or clients.

Coincidentally, I am working on yet another club in this category in North Carolina. It is called Contentment and it has been discussed a little on Golf Club Atlas. The owners of this particular group have adopted the same business model as Sutton Bay and Ballyhack. Their only requirement is that the design be faithful to the “template” holes created by Macdonald, Raynor and Banks. I hope to be under construction on that course before years end.

18. Tell us about the scope of your work at the Country Club of Florida.

Country Club of Florida was my first work in Florida and to be able to work on a course with such an interesting history was a real treat and honor for me. The club was founded by Carleton Blunt, of Chicago, who was instrumental in Western Golf Association and was a founder of the Evans Scholarship Fund. Mr. Blunt was a member of Augusta National Golf Club and decided to create something similar in Palm Beach County Florida in the late 50’s. He engaged Robert Bruce Harris to seek out the best piece of land he could find. Harris found the site near Boynton Beach and began routing the course. Blunt fashioned his club structure and membership after Augusta National. Early on he built cottages for visiting guests and potential members. The ties to Augusta have always been there. The course opened for play in 1957 and has only had four golf professionals. In the first years of operation there were two golf professionals, Johnny Farrell who won the 1928 US Open Championship in a playoff over Bobby Jones, and James Searle who came from Augusta National. The club has only had a few superintendants including Marsh Benson who is currently at Augusta and Jeff Klontz (current) who was also at Augusta National under Benson.

Country Club of Florida is unique in history and equally unique in its terrain. Harris picked a site that has a couple of large natural dunes that dominate the site. I was extremely surprised to find this kind of terrain the first time I interviewed for the job. Harris routing is really brilliant. He uses his “ideal” sequence of 4-5-4-3-4-5-4-3-4 on the front nine and the same 4-5-4-3-4-5-4-3-4 on the back nine. This way you never play the same par on consecutive holes on either nine. More importantly, the routing uses the existing terrain and vegetation so well that there are literally 18 very engaging and separate holes that make up a wonderful rhythm and balance of shots. My job there was not to restore but to upgrade the golf course with newer turf varieties, employ built-in flexibility by enhancing teeing grounds, and create a course that could cater to both the potential new members for the future while remain fun for the existing aging players. It was really challenging but with the help of the board and the staff, I am told we accomplished all of our goals.

19. Speaking of which, let’s talk about bunkers. As seen above, Country Club of Florida features bunkers with more jagged edges, Kinloch’s bunkers feature cleaner lines as typically found at parkland courses and Ballyhack’s bunkers are wild and rugged. How do you decide which bunker style best fits a certain property?

This is a good question. The design “style” can be the make-or-break aspect of every project. Most of the time, the architect has to give certain consideration to the client and the “style” golf course the client is trying to achieve. This is true with respect to renovations probably more than new courses because there is an established “style” that the patrons are used to and changing it is always part of the conversation.

In the case of Country Club of Florida, the course had been renovated in the 80’s. This renovation eliminated the original Robert Bruce Harris bunkers which were huge ovals that dwarfed the greens and were far enough away to drive the gang-mower between the bunker edge and the putting surface. When I got there the bunkers were flat-bottomed sand with steep faces of rough grass on them. The problem the members had was seeing them. I would say that 75% of their bunkers were “out-of-sight” because all you could see was the face, no sand. After interviewing many members, the general consensus (and I agreed) was that the bunkers were “missing” from the course. I was asked that I make the bunkers more visible. I focused on visibility and blending them into an environment that had diverse and dramatic terrain and landscaping. So, I went for diverse and dramatic with the bunkers. Those refined but “jagged edges” allowed for that.

At Kinloch we (Vinny and I) determined that the bunkers needed to be smooth edged and more flowing to reflect the modern, yet traditional style we were trying to develop. Bunkers at Kinloch are usually less busy than those at CCF or Ballyhack and have one or two dominant curves to create the cape and bays. These bunkers tend to embed themselves more into the land giving them a tendency towards subtlety as compared with the CCF bunkers which actually protrude into the surrounding terrain and appear to “spill-out” of normal shapes due to their rough edged shapes.

At Ballyhack I went for a completely unfettered look with an emphasis on creating a look of eroded spoils and cavernous voids. I did not want to see a “normal” bunker that I had been used to on my other projects. During the design process at Ballyhack we noticed many of the scoured out voids where erosion occurred or livestock had tread. We actually spent time trying never to duplicate even similar shapes on two consecutive bunkers. To aid in the creation of this “random” bunkering, we would paint two or three bunkers on one hole and then, before finishing that hole, move on to others so we could avoid any repetition. I even had bunkers built (with drainage and sand installed) and went back and actually had them seeded back with grass to give the appearance of animal burrows that had evolved over time.

This bunker in the ninth fairway at Ballyhack acts as a true hazard and needs to be avoided!

20. Do you think there is a present over-infatuation with bunker styles at the moment? After all, surely bunker placement is more important than bunker aesthetics, yes?

Bunker placement is paramount to any other characteristic as I see it. I am one of those that believe no bunker is unfair. That doesn’t mean to imply that haven’t seen some I thought were ridiculous, I have. In my mind bunker placement is one of the most artistic endeavors we get to employ in our profession. Naturally, we should gravitate toward efficiency and maintenance implications in our designs, but we should also make sure we aren’t over-penalizing every mishit shot. I see so many instances where architects try to overcook their efforts with hundreds of bunkers or vast waste areas designed to complicate the strategy to the point where enjoyment is completely lost. I try really hard to ground my bunker placement and strategy in methods that have worked for me in the past, not just compete with the other guys out there with a “more is better” attitude.

I do think there is an over-infatuation with bunkering styles of late. I am not sure where it is going or where it will end, but with less and less work out there, I am willing to bet we better start seeing some of those trends change or we will be seeing the same course over and over. Architects who think outside of the box and develop different and varying looks will always have plenty to do in my opinion.

Placed in a similar position to the Hell bunker at St. Andrews, these bunkers dominate the second shot on the Long hole at The Old White.

21. Every architect is available for work. Why should a client employ you?

I hate this question! I am extremely proud of the work I do, and at the same time I’m humbled that I am fortunate enough to make a living at what I love. No matter how you answer this question, it sounds like self-promotion.

Since I started in 1989 I have completed over 120 projects on 85 or so golf courses around the country and one in Japan. I have built courses on solid rock (Japan) and in a tremendous variety of soil conditions (good and bad) and in numerous climate zones. I have worked with no terrain (almost flat) and extreme terrain with hundreds of feet of elevation change. I have had water, needed to find water and created water for aesthetics and irrigation. I have worked on private, public, municipal, government and resort courses with a range of budgets from not-enough to too-much. I have designed for charitable organizations, not for profit and for profit clubs and developers. From each and every one of things I have learned valuable lessons and I try to bring this experience to the table every time I interview for a job.

I get up every morning with the same enthusiasm for creating golf courses as I did 25 years ago. I think I bring a lot of experience, knowledge, problem solving ability, leadership and understanding of processes to the table. As Tom Paul once told me, I bring a “macro” big-picture understanding to every project that is simply not there with others. I like to think he is correct. I think I have the right balance of artistic ability combined with technical expertise to work through any problem for my clients. In my business I have consistently surrounded myself with employees, family and friends who challenge me to constantly look at things from differing points of view and demonstrate why and how our solutions work. I can’t abide “yes men” and I won’t tolerate suck-ups. Every one of my employees has a voice.

I also think that the true measure of an architects work is based on his discipline to author great plans and specifications AND spend the appropriate amount of time in the field during construction to implement those plans. I have spent as many as 200 days on site on one project. In my opinion, the best courses (no matter the architect) are revealed by the amount of personal contact that the architect has on that site. I simply refuse to make the “minimum” visits required by contract and I think that distinguishes us to our clients.

In those 20 plus years I have developed a strict process for leading my clients through the morass of issues involved with golf course design and construction as it applies to their unique situation. It is this “process” that has made us valuable to our clients and reliable to their needs. I often say to clients that “the process is as important as the product” which I firmly believe. Armed with this experience and our devotion to the process, we have been fortunate to work on some of the finest clubs and courses in the country.

If a client is looking for a track record of renovation or restoration experience we can proudly point to a list of courses we have worked on that include the works of architects including; Ross, Tillinghast, Flynn, Findlay, Stiles and Van Kleek, McMeniman, Macdonald, Raynor, Banks, Travis, O’Neil, Tull, Wilson, Fazio (George), McCarthy, Harris, Ault (Ed), Gordon and a few others. I think this diversity of architects gives us a distinct advantage to implement our ideas and solutions for a myriad of clients. Even if we haven’t done work on a specific architects course, we spend a great deal of time and effort researching the course history and the architect before implementing any renovation or restoration plans.

If the client is looking for experience in new course design I think we can rely on the success of our original creations and the different kind of courses we have done. I have often told prospective clients that I don’t have a “style”. I would like to think that the site and the client’s needs will point to the direction that our new courses take. Do I have proclivity for certain design strategies or routing imperatives, yes, all architects do. But I will not force them onto a site just to have a “style”. I like to think I truly rely on my routing and design ability to uncover the new courses I design.

I am fortunate to have had local, national (USGA) and PGA Tour events played on my courses and have tried to incorporate lessons learned from those events into my thinking. I am even more pleased to have renovated and (hopefully) improved many golf courses for my clients that have led to more enjoyment for the patrons of those courses. I have donated a great deal of my time to charitable organizations such as the First Tee and other non-profits that try to introduce people (especially kids) with limited access to the game.