Who Was Hugh Wilson? – Part II

By Mike Cirba

September 2013

(Part I published June 2013)

There were unusual and interesting features connected with the beginnings of these two courses which should not be forgotten. First of all, they were both “Homemade”. When it was known that we must give up the old course, a “Special Committee on New Golf Grounds”…chose the site; and a “Special (Construction) Committee” designed and built the two courses without the help of a golf architect…These two committees had either marked ability and vision or else great good luck—probably both—for as the years go by and the acid test of play has been applied, it becomes quite clear that they did a particularly fine piece of work. The New Golf Grounds Committee selected two pieces of land with wonderful golfing possibilities… The Construction Committee laid out and built two courses both good yet totally dissimilar—36 holes, no one of which is at all suggestive of any other. – Alan Wilson 1926

Why Hugh Wilson?

Over a century since Merion East was designed and built, lingering questions remain as to why Hugh Wilson was selected by the club to lead the effort. Certainly, evidence plainly indicates that the club was intent on ensuring that this was an “amateur” endeavor, (Alan Wilson termed it “homemade”) in the sense of the ethos and culture that word evoked in the sporting world of the time, and as exemplified in the golf architectural world by Macdonald, Leeds, Emmet, Fownes and others like George Crump who followed.

But why select Hugh Wilson when others on his Committee like Rodman Griscom and Dr. Harry Toulmin certainly had more years of administrative experience? This article has attempted to profile Wilson the man in a way that accurately reflects his persona and hopefully provides a sense of who he was and why powerful, successful men like Robert Lesley and Horatio Gates Lloyd had such confidence in him. However, the real answer to this persistent question may be as simple as understanding the existing Merion Committee structure and makeup during the time the course was conceived and created.

Merion Cricket Club as a sporting and social organization was a landmark establishment by 1910, having formed in 1865. However, as the name indicates, the well-established sports of the club at the time included cricket and tennis, with golf still a relative and somewhat uneasy newcomer, having only been played by some of the members on leased land for just over a decade. By that time the membership was also playing squash, soccer, billiards, pool, bowling, hockey, and skee ball. Even by 1916 with a rapidly growing golf membership due to the addition of two popular courses the golf membership only numbered 700 out of 3800 total members, less than 20%.

It is important to note that the hefty land purchase the Golf Committee at Merion was proposing in the fall of 1910 was almost certainly not without its detractors and opponents within the club. Indeed, in retrospect it was probably a stroke of business genius for the Golf Committee to tie the acquisition of new lands for golf into a real estate venture that the general membership could benefit from financially. Still, the events of that time need to be viewed with the historical perspective of golf’s proponents trying to elevate the nascent game and its associated costs and risks within the structure of a traditional club with other already well-established areas of social and sporting focus.

The club governance was structured with a President and a Board of Governors at the executive level, and reporting upwards were individual sporting and social “Committees”, each with their own Chairman. As such, there was a Cricket Committee, a Soccer Committee, a Tennis Committee, Squash Committee, Entertainment Committee, Membership Committee, and so on. Individual Committee matters reaching the Board of Governors for determination almost invariably had significant financial or club policy implications.

Under such a broad, federalist system with each activity vying for club attention (and funding), it’s easier to understand the political value of bringing in well-known authorities such as Charles Blair Macdonald and HJ Whigham to vouch for the suitability of the new land Merion was considering for purchase, as well as their subsequent “approve”-ing of the new golf course plan that Merion’s Committee had determined was their best effort, but which required authorization by the Board of Governors for the purchase of three additional acres of land in April 1911.

Understanding the makeup of the MCC general membership of diverse and sometimes competing sporting interests, it also gives new insight into items such as January 1911 letter that went out to all club members notifying them of a dues increase for not only golf members, but any MCC member using the newly planned facilities for Tennis, Skating or “other” facilities at the new golf course. To a membership where a significant majority weren’t golf members, and where the five Construction Committee members (who were appointed that month) had played the game of golf since virtually its inception in the city and held five of the lowest six handicaps at the club, the Merion Board of Governors wrote; “The land has been purchased and settled for and experts are at work preparing plans for a Golf Course that will rank in length, soil, and variety of hazards with the best in the country.”

Golf at Merion at that time was governed by two permanent Committees; the “Golf Committee”, who had domain over all inter-club business related golf and golf club policy matters, and the “Green Committee”, who had responsibility for ensuring the care and upkeep of the golf course and the day to day operational golf issues, the latter reporting to the former. Robert Lesley, who was one of the men responsible for golf coming to Merion in 1896 was Chairman of the “Golf Committee”, and in that role also had responsibility to also create temporary, ad-hoc Committees for special purposes, such as the “Construction Committee”.

Hugh Wilson graduated from Princeton in 1902 and became a member at Merion the following year. Given the fact that he immediately played on Merion’s competitive team in inter-club matches, was named in 1903 to the Philadelphia team to play in inter-city matches, and had spent the previous two years on the Princeton Golf Club Green Committee, coupled with his known interests and acumen, it seems likely that he very quickly would have been named to Merion’s Green Committee with the other top players although the documented record remains incomplete on that particular.

While we still don’t know precisely when Wilson became a member of the Merion Green Committee, it seems extremely likely that the primary reason he was appointed Chairman of the “Special” (as Alan Wilson termed it) Construction Committee” in January 1911 is because he was already serving as Chairman of the Merion “Green Committee” at the time, with considerable tenure in that role.

In 1934, writing for the US Open program, then Club President Robert Lesley wrote; “In connection with these two courses, both of which are of championship character and have received the most favorable comments in golf circles all over the world, it may be stated that the reason for this successful development is due to the fact that during this period from 1909 to the present day Merion’s Green Committee has been kept almost intact from its origin up to today and only five Chairmen of the Green Committee have had charge of the work and development of the courses, thus insuring a consistent, systematic, and wise development. These Chairmen were; Hugh I. Wilson, Winthrop Sargent, and John R. Maxwell, who are now deceased, and Arnold Gerstell and Philip C. Staples.”

It should be noted that Maxwell, Gerstell, and Staples all served in the later 1920s and early 1930s after the death of Hugh Wilson, and that Lesley’s listing of Chairmen is in chronological order. Winthrop Sargent served consecutively during the period from late 1914 until at least 1923 (according to Spalding’s “American Annual Golf Guide”), and in fact took over from Hugh Wilson when the latter resigned, as recorded in the MCC Minutes of November 23, 1914;

“The resignation of Mr. Hugh I. Wilson, as Chairman of the Green Committee, was presented…the following resolution was adopted:

RESOLVED, that in accepting Mr. Wilson’s resignation as Chairman of the Green Committee, this Board desires to record its appreciation of the invaluable service rendered by him to the Club in the laying out and supervision of the construction of the East and West Golf Courses. The fact that these courses are freely admitted by expert players to be second to none in this country, demonstrates more fully than anything else that can be said, the ability and good judgment displayed by Mr. Wilson in his work.

The Board desires to express on behalf of the Club its sincere thanks to Mr. Wilson and its regret that pressure of business makes it necessary for him to relinquish the duties of Chairman of this important committee. On motion duly seconded, Mr. Winthrop Sargent was appointed a member of the Golf Committee and Chairman of the Green Committee.”

Sargent had previously served as Chairman of the Green Committee in 1911, which would make perfect sense as Hugh Wilson had been appointed to head the new “Construction Committee” in January of that same year, charged with responsibility for creating the new course. At the time, the club needed both roles filled as they were simultaneously serving the needs of the golfing membership at their original course at Haverford while casting an excited eye on their future in Ardmore.

Interestingly, there seemed to be some significant overlap in both membership and responsibility between the “Green” and “Construction” Committees and it is likely the latter was a subset of the former. Robert Lesley, who was Chairman of the standing “Golf Committee” at the time the Merion courses were designed and built wrote in 1934; “Hugh I. Wilson and his Green Committee laid out Merion’s first course on the new land and it is now what is known as the “East Course”.” Lesley later continued, “…a second eighteen hole course, now known as the “West Course”…was created by Hugh I. Wilson and his associates on the Green Committee.”

Given that the primary role of the “Green Committee” was overseeing the care and development of the golf course, it should hardly be surprising that after decisions were finalized to purchase the new property in December 1910, the major responsibilities of at least some of this Committee would have shifted from the leased course they were leaving in Haverford to the creation of the brand new, club-owned course in Ardmore.

It was also common practice in Philadelphia (and other cities) at that time for the Chairman of the Green Committee of various clubs to undertake what is today regarded as golf course architecture, and almost an expectation of the job. This effort often took the shape of trying to make significant improvements to their often “professionally-designed”, turn-of-the-century, courses in an effort to make them more challenging for the new, longer ball and an increasingly popular game in the city.

Green Chairmen such as Edward Bispham at the Philadelphia Country Club, Samuel Heebner at Philadelphia Cricket, Rodman Griscom at early Merion, Henry Strouse at Philmont, and A.H. (“Ab”) Smith at Huntingdon Valley all worked continually at adding bunkering, rebuilding greens, as well as creating brand new holes and lengthening others.

Others such as George Klauder at Aronimink, George Thomas at Whitemarsh Valley , and J. Franklin Meehan at North Hills each had opportunity to significantly contribute to the design of brand new courses during this period, each working with other prominent members of their respective clubs.

In the case of Hugh Wilson, in April of 1916 “Philadelphia Public Ledger” golf-writer and local insider William Evans wrote, “The changes have been made by the Green Committee under the most efficient chairmanship of Winthrop Sargent and Hugh Wilson, to whose genius Merion owes both its courses.” The article was referring to the extensive changes made to Merion’s East course during 1915-16 in preparation for the 1916 US Amateur. A similar article that month in the “Philadelphia Inquirer” was not nearly so ambiguous in terms of the specific roles of the two men at the time, noting; “Nearly every hole on the course has been stiffened so that in another month or two it will resemble a really excellent championship course. Hugh Wilson is the course architect and Winthrop Sargent is the chairman of the Green Committee. These two men have given a lot of time and attention to the changes and improvements.”

The Evans article went on, “In addition, Mr. Wilson, for many years chairman of the Green Committee at Merion…” This is particularly noteworthy because at the time this was written, Wilson had not been Green Chairman since his voluntary resignation in November of 1914. If Wilson’s tenure as Green Chairman had only been from 1912 until November 1914 it seems quite unlikely that Evans would have termed it “many years.”

That same year, writing for the Chicago-based publication, “Golfer’s Magazine”, Evans wrote; “The new Merion courses are largely the work of Hugh I. Wilson, for a number of years chairman of the green committee. He has had as his assistants in laying out the courses R.S. Francis, H.G. Lloyd, R.E. Griscom and Dr. Hal Toulmin with Charles B. Macdonald and J.H.J. Whigham as the advisers.” Again, it’s very doubtful that Evans would have termed a less than two-year tenure, “a number of years”.

In 1923, another well-connected local golf-writer J.E. Ford (using the pen-name “Donnie MacTee”) claimed that Wilson served seven years as Chairman of the Green Committee before his voluntary retirement; “Responsible for these improvements in the already unsurpassed east course is Hugh Wilson, a pioneer golfer here and chairman of the Merion green committee for seven years – or until his voluntary retirement.”

“Mr. Wilson was one of the original designers of the Merion course and the holes just constructed are the ones he wished for, but was prevented from building when the course was designed. He is still a very active member of the greens committee, to whom all questions of architecture and grasses are referred as a matter of course.”

Of course, “seven years” as Chairman before his “voluntary retirement” is much more consistent with the “many years” in that role that Evans wrote in 1916. If accurate, and there is no apparent reason to doubt the veracity or understanding of Lesley, Evans, or Ford, it would have placed Hugh Wilson in the Chair of the Merion Green Committee from approximately 1908 through 1914, (with the exception of 1911 as discussed prior) consistent with the timeframe Robert Lesley later referred to when he wrote that continuity of the Committee Chairmanship was responsible for the success of Merion’s golf courses. It would also seem logical that Wilson would have served as a Committee member for some years prior to being appointed Chairman.

If these reports are accurate, Hugh Wilson would also have been Chairman of the Green Committee in 1909; the year Merion hosted the US Women’s Amateur on its original course in Haverford. That course had nine holes originally designed by Scottish professional Willie Campbell in 1896 with ensuing revisions and another nine added by Rodman Griscom and his Green Committee in 1899.

For the prestigious U.S. Women’s Amateur tournament, which was won by Dorothy Campbell, work had been done prior in an attempt to get the golf course up to competitive tournament standards. A.W. Tillinghast wrote in his preview of the tournament in “American Golfer”; “New pits have been judiciously placed and the course requires more playing now.”

Max Behr, writing for “Golf Illustrated” in 1914 noted; “By far the best work in this or any other country has not been done by committees but by dictators. Witness Mr. Herbert Leeds at Myopia, Mr. C. B. Macdonald at the National, and Mr. Hugh Wilson at the Merion Cricket Club. These dictators, however, have not been averse to taking advice. In fact they have taken advice from everywhere, but they themselves have done the sifting. They have studied green keeping and course construction as it was never studied before. And they have given the benefit of their studies to the world at large.” It seems sensible to consider that no one accumulates that type of power within a golf club without significant tenure, and accompanying respect. However long Wilson served as Chairman of Merion’s Green Committee, it is clear that none of his predecessors in the Philadelphia area were more painstaking in their approach – or more successful in their results.

A last word about Committees; although for convenience purposes we refer to Wilson’s Committee as the “Construction Committee”, the Merion Cricket Club Minutes never referred to it as such. Alan Wilson’s later account first called it a “Special Committee” and later, a “Special Construction Committee” who “designed and built the two golf courses without the help of a golf architect”, while Robert Lesley simply referred to them alternatively as “a committee” and “Hugh Wilson’s Green Committee” who were responsible for both courses. Richard Francis termed the team he was “added” to, “The Committee in charge with laying out and building the new course.”

Whatever the terminology, we do know that contemporaneous press accounts used the term “Construction Committee”, which has sometimes confused modern observers. Given our modern day understanding of divisions of labor we tend to view the word “construction” as including only the building process, and not the design. But that is not accurate from either a historical or an etymological standpoint and with a few examples, it becomes clearer that the men involved were using this term in a holistic fashion, to mean “something fashioned or devised systematically”.

In March of 1913, when George Crump and his committee were in the process of designing and building Pine Valley, and several months before Harry Colt’s arrival, Tillinghast wrote; “The Construction Committee is working slowly but surely. No hole will be constructed until it has been tried out very thoroughly during the summer months and as quickly as it is cleared. It is gratifying to notice that the old Philadelphia evil of parallel holes is being avoided. The committee is determined that the fairways shall be far enough apart to preclude the possibility of playing from one to another…the Pine Valley builders have not lost sight of this vital feature of modern course building. Then too, greens that are reached with irons are being more closely trapped than formerly, and the pits are constructed on a more ambitious scale.”

Donald Ross, writing an essay in 1910 on a tour of British Golf Courses (recently unearthed by historian Chris Buie) made the synonymous usage of terms like “constructor” and “architect” at that early time even clearer. Ross wrote; “Perhaps of more striking and general importance to the players of golf here than anything discovered, certainly the one fact that proved the most stimulating and the most satisfactory to myself, was that anything that has been done by course architects and constructors in this country, which has been criticized as radical and extreme by home players, does not hold a candle to the work of the people on the other side of the water make their courses a severer, and therefore a better test of the game. Much of this construction work, or rather on many links much of this laying out of the courses, has been done during the past few years and whether in some cases the architects have gone too far is a question that time will answer….”

Ross continued; “The British architect of golf courses pays little heed to criticism, but is always open to valuable suggestions, knowing full well that the carping critic is usually a very ignorant man, while the one who has any advice worth taking gives it in the gentlest way knowing that no two experts ever agree exactly on the points of golf course construction and that the best courses usually are the outcome of a compromise of ideas gathered from many intelligent sources. For instance, they do not lay out a course by rule of thumb, with the idea of having the drive such a distance, the approach such a distance, and so on, even mentioning the clubs that shall be used for each shot. The course constructor casts his eye over the country and gets the idea of what he considers a good golf hole in his brain, lays it out that way, then says to the player : “There’s the golf hole, play it anyway you please.””

Wilson’s Architectural Legacy

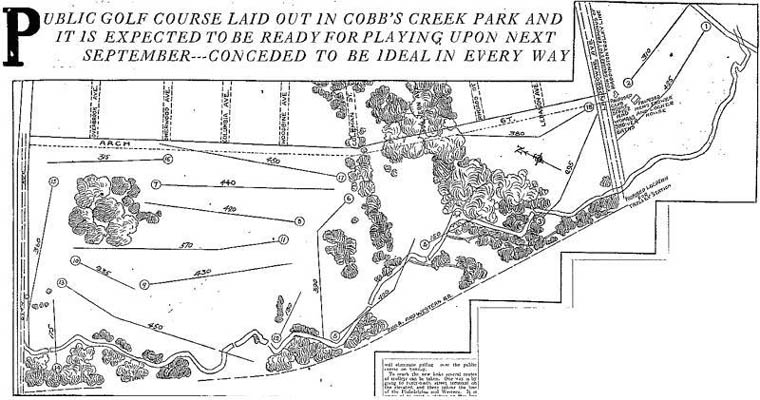

Years after Wilson’s death, George Thomas, who created such gems as Riviera and Bel-Air on the west coast, wrote; “I always considered Hugh Wilson of Merion, Pennsylvania as one of the best of our golf architects, professional or amateur. He taught me many things at Merion and the Philadelphia Municipal (Cobb’s Creek) and when I was building my first California courses, he kindly advised me by letter when I wrote him concerning them.”

Hugh Wilson always preferred to let his architectural work speak for itself, and in that regard we are fortunate that most of his architectural work survives in fine fashion, with all of the courses where he worked still in existence. Certainly the courses at Merion still bear much of his stamp, but one wonders what Wilson would have thought about recent efforts to wring every last bit of yardage and to narrow fairways to slender ribbons through swards of deep rough as a defense against the best players. Wilson’s work also reflects a penchant for heavily sloped greens that reflected their natural surrounds so it’s likely he may have been concerned that modern green speeds would require them to be somewhat leveled, as the twelfth and fifteenth greens at Merion have been in recent times.

What little Wilson did say or write about architecture may provide some insight; “Hugh Wilson, who built the two fine courses at Merion believes every club would have better putting greens if it were not for the craze for lightning-fast greens. The reason why it is necessary to seed the greens every year is that excessive cutting prevents the grass from seeding, and it is necessary each year to put seed into the green. He says clubs would be much better satisfied if the grass on the putting greens were allowed to grow a little longer instead of having them like the surface of a billiard table.”

Certainly Wilson’s career shows he was not averse to evolving golf courses to reflect changing needs, but one senses that he would also recognize that there are practical limitations of acreage and cost that should be considered. In that regard, as a man who worked to fit great golf holes on some tight properties, it is very possible that Wilson would have agreed with his friend George Crump, who argued in 1917 for a standardized golf ball; “Golf Clubs cannot afford to construct expensive courses and then have all that work undone by a golf ball that anyone can buy….unfortunately, the golf ball makers each year are turning out new balls that can be driven further…if it keeps up, we shall have to change all our bunkering to suit the new ball, or else bar certain balls from being used. No club would care to do the latter, yet the expense of re-bunkering a course would be tremendous. If even the poorer players can discover a ball that can be driven two hundred yards or more we will find that all our bunkering has gone for nothing, and the three-shot holes will be easy two-shot affairs, and the two-shot holes nothing but a drive and a mashie (wedge) approach. In addition, none of the traps over which we have spent so much time would longer server their purpose.”

Wilson often worked in collaboration with others, seeking advice from experts, and sharing freely when he became an authority, as well. In today’s competitive architectural world, such methods likely seem quaint, yet the very collegial methods employed by Wilson and others of the time served to create some of our finest courses that have stood the test of time. Likewise, the idea of first creating the basic shell of a course, which then would be built up over time through the addition of features and hazards as play was observed and studied would be very expensive, if not completely impractical using today’s construction and irrigation methods.

However open Wilson was to seeking and heeding advice, it also seems that he was the ultimate decision maker and resident expert at Merion in matters of architecture and agronomics, as evidenced by Max Behr’s 1914 characterization of him (along with Herbert Leeds of Myopia and C.B. Macdonald at National) as “dictator”(s) within their respective clubs.

While Wilson’s early architectural style was derivative of courses he sought to emulate, he also exhibited a natural flair for routing and following what was suggested by nature to a greater degree than many of his predecessors. While numerous early pioneers routinely placed their greens at the highest and lowest points of the property, Wilson’s greens are most unusual in their frequent placement at a slight offset just shy of the elevation peak, which serve to both increase their visibility as well as the degree of natural slope. Fine examples of such are still found on the 12th and 15th at Merion East, the 5th at Merion West, and the 2nd at Cobb’s Creek.

Wilson’s greens on lower points of the property tend to be located just beyond the lowest point where the ground began to rise on the far side, often behind streams or creeks, such as the 4th and 9th at Merion East, the 9th at Phoenixville, and the 17th and 10th at Merion West. Again, this served to be effective in terms of increased visibility, natural drainage, and degree of challenge.

When dramatic landforms were available, Wilson was not averse to locating his greens right on the very edge of precipitous falloffs, creating approach shots that increased the pulse rate by appealing to the visceral need of the golfer for a sense of adventure. Wonderful examples can still be seen on the 7th and 15th at Cobb’s Creek, the 7th at Merion East, and the 10th and 11th at Philmont South where a ball missing to the wrong side can easily cascade down steep embankments.

Where less remarkable land was available, Wilson had an affinity for building tasteful greens that seem mere extensions of the fairway as evidenced by the 5th at Merion East, the 5th at Cobb’s Creek, or the long par-three 11th at Seaview.

Like many of the earliest architects, Wilson was not averse to using blind shots in his repertoire, yet in placing his bunkers, legend has it that Wilson would have Joe Valentine lay out white sheets in the distance, so insistent was he on visibly revealing them to the golfer. Instead, most of Wilson’s blind shots are from the tee, with often the fairway itself hidden from view. Merion East has many examples, most notably the drive over the rise of the quarry wall on the 18th, but it worked in reverse, as well, on holes where the fairway was located far below the player and out of sight such as the 11th. Both Cobb’s Creek and Merion West have significant examples of the form, where the golfer needs to drive to the top of a sharp rise, the fairway concealed beyond. Prime examples include the original 6th and today’s 10th at the former, as well as the 5th and 18th at the latter.

Wilson seemed to have a love for creating sharply downhill, “drop shot” par threes, usually with a green located just beyond a creek, such as the 9th at Merion East, and perhaps most definitively and more dramatically, the 6th at Merion West, the 2nd at Phoenixville, and the original island-green 12th at Cobb’s Creek which is no longer in existence. The combination of lasting beauty, uncertainty, and accompanying drama makes one wonder why such holes are rarely built today.

He also seemed to have an early, almost instinctual understanding of the concept of “half-pars”, and the variance of yardage seen in his courses was virtually unprecedented. Every one of his courses includes one very short and one very long par three, with others in the mid-range. Seaview for instance, has the diminutive 17th at 110 yards, and the protracted 11th at 240, both with greens protected commensurate with their shot demands.

All also include par fours ranging the gamut from drivable holes in the 280-320 range alongside beasts requiring two solid blows with long clubs. Merion West’s almost petite 7th and 8th holes, for instance, are followed by the long, uphill 9th, much as Merion East’s pitch shot 13th is followed by the lengthy uphill 14th, with a fearsome stretch to follow Such balance and variety serve to not only keep the golfer off-kilter, but also serves to keep the shorter hitter from being discouraged by hole after hole featuring long, demanding slogs.

Wilson was also an early adopter of using a “great hazard” on par fives, often in the form of an intervening cross-bunker (ala the Hell bunker) that needed to be carried on the second shot. Good examples of this type of hole are seen at the 4th at Merion East, and the 9th at Seaview. He was not averse to employing much the same strategy on a par four, where he sometimes used cross hazards, usually on a diagonal to both hide the fairway target as well as create options for lines of play. Many of his par fives are reachable in two today with modern equipment, but one senses most were built with the intent of being true three-shot holes requiring precise placement and distance control to reach the green in regulation.

While many of Hugh Wilson’s greens permit a running approach, particularly on long holes, he often required full-carry approaches with shorter irons. When a natural hazard wasn’t available to use, he would place a bunker across the entire front of the approach

Of course, where streams, ditches, and creeks were available to Wilson, he used them with relish. Perhaps his trademark hole is the short, downhill par four to a bend in the waterway, with the creek then wrapping around two or three sides of the green. With magnificent early examples of the type already built on the 10th at Merion West and the 3rd at Cobb’s Creek, he perfected the form by 1922 when Merion was able to acquire land along the creek they originally wanted in 1910 with the creation of the diabolical 11th at Merion East.

Getting such wonderful variety of golf holes out of a property was likely a distinct result of Wilson’s careful study of the available natural landforms and a routing methodology that was not restricted by convention. For instance, none of Hugh Wilson’s golf courses have a ninth hole that returns to the clubhouse, a practice that tends to tie the architect’s hands for convenience sake. Instead, all of Wilson’s original routings have the ninth out somewhere in the middle of the course, the better to maximize the entire property and give the course a sense of journey.

It seems quite possible that this was a practice Wilson learned from C.B. Macdonald, as NGLA’s ninth hole was/is an out and back routing with the 9th (today’s 18th) at the furthest point from the clubhouse. Whatever Wilson’s inspiration, that decision was also likely vindicated by the number of great, famous courses abroad Wilson visited later which did not have returning nines.

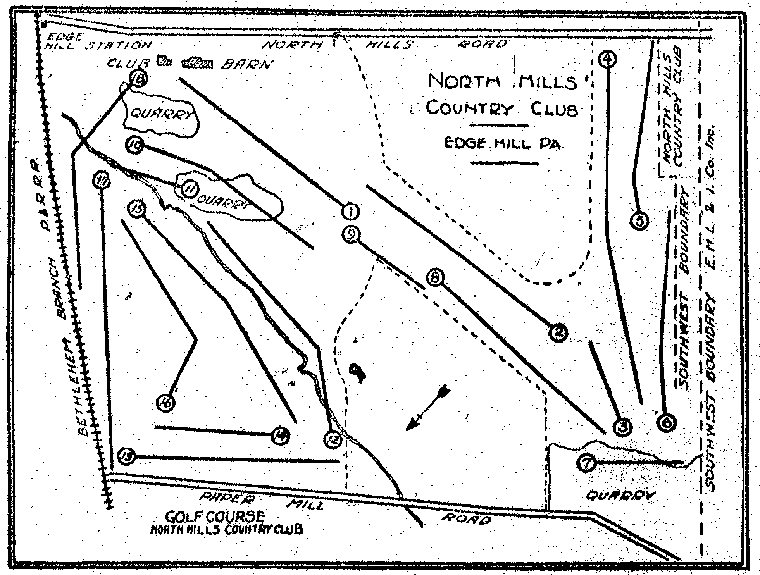

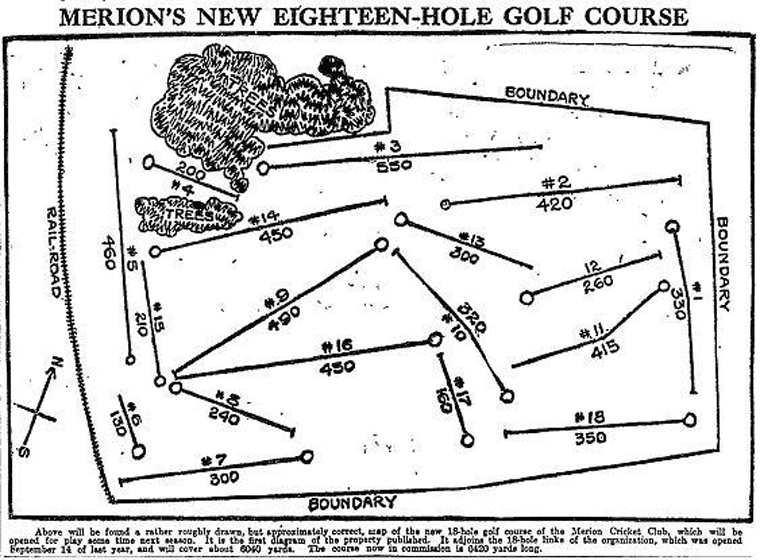

Wilson’s routings usually started by following along the eastern property line in a counter-clockwise fashion, and then at some convenient (or dramatic) point penetrate directly into the property, often then turning in a concentric circular fashion in the other direction. These “circles within circles” were an effective way of creating mini loops of holes that could all use a particularly interesting landform in different ways and from different angles. Sometimes, as in the case of Merion East, Wilson routed the countering loop outside the original one, creating more of a figure eight configuration of holes. The original layout of the four courses where we know Wilson was involved in the routing follow below.

Below is the earliest found routing drawing of Merion East from 1916, sketched by William Flynn. It should be noted for historical understanding that this drawing shows the extensive bunkering done by Wilson and Merion during late 1915/early 1916 in preparation for the 1916 US Amateur, (likely around 50 added) as well as newly rebuilt greens on holes 3 (today’s 6th), 8, 9, and 17.

It should also be noted that the course routing was changed for this tournament so that today’s 3rd through 7th holes played as holes 7, 5, 6, 3, and 4, respectively. Sometime after the tournament, the course was returned to the original routing which is the same as todays.

Through the photographs and routing examples contained in this article, one can get a good sense of Wilson’s consistently appealing and judiciously prudent use of landforms and man-made architectural touches across his various courses, but much like Donald Ross at Pinehurst #2, none of Wilson’s courses but Merion East benefited from his almost constant attention, wholesale revisions, and detailed tinkering throughout his life. The primary reason for that is simple; not only was Merion East his first course but once it became Philadelphia’s new “championship course” in 1916, the perceived need to make it a stringent and fascinating test to challenge the very best players is a tradition begun at that time which continues to this day. It is interesting to consider that between the time Merion East opened in 1912 until the time of Wilson’s death in 1925, upwards of 100 bunkers had been added, 4 completely new holes were created (replacing original holes 10, 11, 12, & 13), and at least 8 new greens built. A decade later another original hole and green (the 1st) was replaced and another 3 greens rebuilt (1, 2, & 14).

Perhaps Wilson’s most lasting architectural legacy and one most worthy of study and emulation today was his pioneering work in combining naturalness, the blending of artificial construction seamlessly into the surrounding landscape, with the creation of golf holes that are fun for everyday play, where recovery is always a possibility, and that are adaptable to stringently challenge top players in competition. Indeed, Hugh Wilson’s courses today give the impression of very little moved in the way of dirt, where good golf holes are found through careful study of what nature offered instead of being jack-hammered, exploded, and plowed into existence.

Wilson’s greens often contained significant slope, but also had tremendous variety in internal contouring. During his career, Wilson built everything from punchbowls, to inverted saucers, from steep false fronts to greens falling subtly away from the player at the back. Many of his greens slope not only from front to back, but with pronounced slope from side to side. Most tend to fall away around the edges, though on a number of his courses, most notably Seaview, some of the green sizes have shrunk considerably over the years through altered mowing patterns. That’s a shame, because some of Wilson’s most interesting and precarious hole locations tend to be out towards the corners of the fill pads. Indeed, at the time it was built Seaview was noted for having greens that were marvels of undulation and cunning on par with any in the country. Today, some of his best and most original greens, however, simply seemed to mirror nature, with various subtle ripples, dips, protrusions, and valleys seemingly placed at random, such as the wonderful 15th at Merion West, and the lovely 11th at Cobb’s Creek.

Although Wilson had an imitative flirtation with the creation of large, ostentatious earthworks such as the original “Alps” 10th at Merion during his earliest “experimentation” period, he soon settled into an elegance, simplicity, and economy of design that mirrored his reserved, conservative personality. Most of his greens and tees flow from the fairway or surrounds “at grade” from the highest or lowest point, and are only almost imperceptibly built up, or cut on the opposite side, the dirt garnered through the digging of adjacent bunkering, or the excess used for soft mounding. This approach has proved timeless, and has led to the beautiful simplicity of naturally-sloping, subtly-devilish greens like the 5th at Merion East, the 10th at Philmont, the 14th at Merion West, and the 12th at Cobb’s Creek.

However, by contrast, and quite ironically considering that Merion East and most of Wilson’s courses had a scarcity of bunkers in their early years, it is Wilson’s innovatively bold, distinctive, yet naturally appearing bunkers that ultimately are his most noteworthy architectural feature.

Indeed, the Merion bunker “style” has become iconic. Often imitated, but rarely duplicated as successfully, at their best they look as weathered and distressed as the face of a retired sea captain, the steep rise of their faces seeming at times to be near tippling, cracking, and tumbling back into the hellish pits from whence they came. Today at Merion East the bunkers have somewhat morphed in recent years, deepened, but stabilized with thick faces of turf and fescue that seem an accommodation to both modern equipment and practical maintenance considerations. Over time, the rebuilt bunkers have begun to weather into their own distinctive look, but to some observers with heightened aesthetic sensibility, mores’ the pity in comparison to the Wilson originals.

Wilson wrote, “The question of bunkers is a big one and the very best school for study we have found is along the seacoast among the dunes. Here one may study the different formations and obtain many ideas for bunkers. We have tried to make them natural and fit them into the landscape. The criticism had been made that we have made them too easy, that the banks are too sloping and that a man may often play a mid-iron shot out of the bunker where he should be forced to use a niblick. This opens a pretty big subject and we know that the tendency is to make bunkers more difficult. In the bunkers abroad on the seaside courses, the majority of them were formed by nature and the slopes are easy; the only exception being where on account of the shifting sand, they have been forced to put in railroad ties or similar substance to keep the sand from blowing. This had made a perfectly straight wall but was not done with the intention of making it difficult to get out but merely to retain the bunker as it exists. If we make the banks of every bunker so steep that the very best player is forced to use a niblick to get out and the only hope he has when he gets in is to be able to get his ball on the fairway again, why should we not make a rule as we have at present with water hazards, when a man may, if he so desires, drop back with the loss of a stroke. I thoroughly believe that for the good of Golf, that we should not make our bunkers so difficult, that there is no choice left in playing out of them and that the best and worst must use a niblick.”

After Wilson’s death in 1925, his brother Alan may have summed up his architectural legacy best when he wrote a year later; “The most difficult problem for the Construction Committee…was to try to build a golf course which would be fun for the ordinary golfer to play and at the same time make it really exacting test of golf for the best players. Anyone can build a hard course—all you need is length and severe bunkering—but it may be and often is dull as ditch water for the good player and poison for the poor. It is also easy to build a course which will amuse the average player but which affords poor sport for players of ability. The course which offers optional methods of play, which constantly tempts you to take a present risk in hope of securing a future advantage, which encourages fine play and the use of brains as well as brawn and which is a real test for the best and yet is pleasant and interesting for all, is the “Rara avis”, and this most difficult of golfing combinations they succeeded in obtaining, particularly the East course, to a very marked degree. I think the secret is that it is eternally sound; it is not bunkered to catch weak shots but to encourage fine ones, yet if a man indulges in bad play he is quite sure to find himself paying the penalty.”

“We should also be grateful to this committee because they did not as is so often the case deface the landscape. They wisely utilized the natural hazards wherever possible…We know the bunkering is all artificial but most of it fits into the surrounding landscape so well and has so natural a look that it seems as if many of the bunkers might have been formed by erosion, either wind or water and this of course is the artistic result which should be gotten.”

“The greatest thing this committee did, however, was to give the East course that indescribable something quite impossible to put a finger on,—the thing called “Charm” which is just as important in a golf course as in a person and quite as elusive, yet the potency of which we all recognize. How they secured it we do not know; perhaps they do not.”

The author wishes to again gratefully thank Pete Trenham, PGA, for the 1934 US Open Program found at his wonderful site, http://www.trenhamgolfhistory.org/ and Joe Bausch for his unparalleled research efforts, as well as for the liberal use of his photo catalog, the “Bausch Collection”, which can be found here; http://myphillygolf.com/gallery.asp?id=7479&pid=2236 Additional photos have been copped from the pages of Golf Illustrated and George Thomas’s “Golf Architecture in America”, and the online Dallin Library of the Hagley Museum, Wilmington, DE.

THE END