A Cry for the Golf CourseThe Case for a Comprehensive Tree RemovalProgramAt the Philadelphia Cricket Club Flourtown (PA) Course, USA

by Gib Carpenter

November, 2007

I have been a member of the Philadelphia Cricket Club for sixteen years. My other Club memberships are at Waterville in Kerry, Ireland since 1997 and more recently (since 2005), Hidden Creek Golf Club, the new Coore & Crenshaw course in Southern New Jersey.

I have served on the Cricket Club’s Golf Committee for more than a decade. I also served for several years as Finance Chair on the Committee that undertook the successful effort to build a second championship course at PCC, the Militia Hill Course (Michael Hurdzan & Dana Fry) which opened for play in 2002. I served on the Club’s Admissions Committee for six years and have been responsible for bringing literally dozens of new golf members to the Club over the years. I believe it is fair to say that I would be considered an Ëœinsider” at the Club, with access to decision makers at both the Committee and Board level. However, I have been absolutely stonewalled for years whenever I have attempted to make the case for tree removal at the Clubs 1922 Tillinghast course at Flourtown, and so I am making the case here in hopes of encouraging discussion (and hopefully support) among those members of the golfing community with an interest in golf history and course architecture.

Background

Albert Warren Tillinghast was at the vanguard of what has been described as the “Philadelphia School” of golf course architecture that so greatly contributed to the “Golden Age” of course design in America, centered roughly around the decade of the 1920’s. Along with Tillinghast, notable Philadelphian’s such as William Flynn, Hugh Wilson, George Crump and George Thomas built courses which not only transformed the golfing landscape in America but remain to this day the standard by which other courses are measured. The USGA and PGA continue to seek out these courses to host their greatest championships (Winged Foot, Baltusrol, Bethpage, Shinnicock, Cherry Hills, Riviera, et al) and those clubs lucky enough to enjoy an example of such masterworks for the most part take great pride in their role as stewards of an important piece of the games history in this country.

The Philadelphia Cricket Club (along with Merion Cricket Club, Aronimink Golf Club and Philadelphia Country Club) was a founding member of the Golf Association of Philadelphia, which traces it’s history to 1897 as the country’s oldest regional golfing association

The Philadelphia Cricket Club’s course at Flourtown is, I believe, a unique and historically significant course in that not only is it the only remaining example of Tillinghast’s work in the Philadelphia area, but Tillinghast himself (along with Thomas, an early winner of the Club Championship) was a longtime PCC member. An accomplished player prior to embarking on his career in course design, Tillinghast twice represented PCC in the US Open when it was contested over the Cricket Club’s original 18-hole course at St. Martins in 1907 and 1910.

When the Cricket Club acquired 310 acres in nearby Flourtown with the intent to build thirty-six new championship holes (and perhaps relocate the entire Club) they naturally turned to member Tillinghast to undertake the design. Ultimately, the decision was made not to relocate the main Club and Tillinghast completed only eighteen holes on 135 acres. The adjoining 175 acre parcel remained in Club hands and was used primarily for pheasant hunting for the rest of the twentieth century until the Militia Hill course was finally opened in 2002.

Tillinghast’s Flourtown course opened on Labor Day, 1922.

In My Opinion

It is my opinion that the Philadelphia Cricket Club’s Tillinghast course at Flourtown, PA is in dire need of a comprehensive tree removal program.

Over the past decade virtually every Club lucky enough to enjoy a great course from the “Golden Age” has had to come to grips with the need to remove trees to a) improve turf conditions by increasing sunlight and air circulation and b) restore intended playing characteristics which had been lost to the encroachment of trees. These projects (and in many cases the uproar amongst the membership at the prospect of removing trees) have been well documented.

Nationally, the removal of thousands of trees from Oakmont first brought the “tree issue” to the forefront of discourse more than a decade ago. Likewise, Jack Nicklaus’ famous observation at the 1996 PGA Championship that Tillinghast’s Winged Foot West Course (1923) had become a “jungle” which he no longer recognized spurred that Club to remove over a thousand trees each from both of it’s historic courses. Locally, Merion (Wilson, 1912), Aronimink (Donald Ross, 1928), Philadelphia Country and Rolling Green (Flynn, 1927 & 1926 respectively) have all removed anywhere from several hundred to over a thousand trees each to universally positive critical response.

To date Philadelphia Cricket Club has declined to entertain any serious discussion to address the tree situation at Flourtown. In my opinion the unwillingness to deal with this issue has allowed course conditions and playability to deteriorate to the point that the course’s rightful place in the pantheon of great classic courses has been severely compromised. While we all have our opinions about the legitimacy of the various course ratings, it simply cannot be ignored or rationalized that the Cricket Club’s course at Flourtown, a 1922 Tillinghast design and once-perennial “Top 100 in the U.S.”, was recently omitted from Golf Digest’s list of the Top 25 Courses in Pennsylvania.

(http://www.golfdigest.com/images/rankings/gd200705bestinstate.pdf)

Before and After

Tillinghast laid out the Flourtown course on a wonderful piece of land, perfectly suited for a parkland golf course – rolling farmland with gradual elevation changes bisected by a creek. Situated next to the nations oldest (and still working) limestone quarry, the soil is rich in nutrients. According to the Club’s Greens Superintendent, the property as Tillinghast found it contained a grand total of six trees.

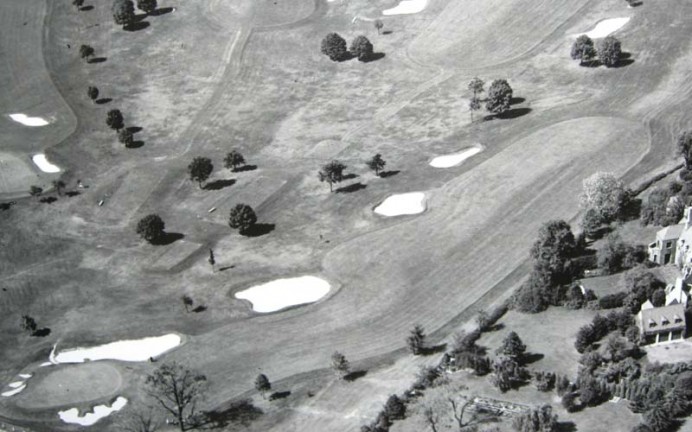

Below is an aerial photo dating from October, 1938, some sixteen years after the course opened for play. The photo shows holes twelve through seventeen in the foreground with most of the front nine visible in the background. The sixteenth tee at lower left and fifth green at top right are the two highest elevation points on the property and (despite the first generation of tree-planting) offered sweeping vistas across the course.

Aerial 1, 1938

Below is a photo dated June, 2007 from the same perspective:

Aerial 2, June 2007

And another current photo from the opposite side:

Aerial 3, 2007 from opposite side

Compared to the Same View from 1938:

Aerial 4 in 1938

I make this historical comparison not to suggest that trees should be removed to the extent that the course be returned to it’s aspect of 1938, but rather to illustrate just how drastically altered any course will become when subjected to 85 years of unchecked tree-planting and growth. Invariably, it has been my experience that whenever the topic of tree removal has been broached at the committee level, those opposed to removing trees have rushed to claim the perceived moral high ground of not “tampering” with the Tillinghast design. However, it is my opinion that any truly open-minded reflection on the “before and after” aerials above must inevitably lead to the conclusion that when it comes to large growing organisms such as trees that, once planted, the results of “doing nothing” is obvious and dramatic.

Indeed, it seems to me that the argument can be made that through relentless tree-planting by generations of Grounds Committees with no long-range management plan, and for the most part without input from any golf course architect (let alone Tillinghast), that the Club has been “tampering” with the original design for decades by engulfing the course in a forest of its own creation long after Tillinghast’s work had been completed.

Tillinghast’s View of Trees on the Golf Course

Tillinghast himself was an admirer of trees in proper context on the golf course. In his historic work “The Course Beautiful” Tillinghast wrote of trees’ beauty and place in adding charm to a course and influencing play where appropriate. He also lamented the fact that it was sometimes necessary to remove beautiful specimens during the course of construction. However, Tillinghast was very direct in his view that “we may play around trees but certainly the only route to a hole must never be over or through them…we must not have them directly by our putting greens (and) not too close to the line of play’ further, he states that ‘respect is paid to fine old trees which stand out gloriously as ‘small stuff’ has been removed…’

To reiterate, in Tillinghast’s view: “we must not have them directly by our putting greens (and) not too close to the line of play”

In my opinion, decades of aggressive tree planting at Flourtown has left the course sorely lacking in adherence to these ideals. Trees which were planted too close together and too close to fairways, tees and greens (presumably in a misguided attempt to add “separation” and “framing”) have been allowed to grow to the point that virtually every hole has become a “bowling alley” flanked on either side by an unbroken phalanx of mature trees, each one growing into the next (see Aerial 3). Virtually all greens and tees are likewise surrounded by huge trees of all types. The resulting impact on turf conditions is predictable. As a direct result of the overcrowding with trees the course does not receive adequate sunlight and air circulation, the result being substandard turf conditions that, despite the best efforts of the Grounds Committee and course superintendent, continue to deteriorate every year. In the past five years alone the Club has undertaken several projects in an attempt to address particularly troublesome areas, notably tees and greens, with consistently disappointing results.

Further, the unchecked planting and growth of trees has directly resulted in the alteration, removal or destruction of many of the best design features (i.e. bunkering, intended lines of play) that the course was meant to feature, as I believe a hole-by-hole examination will show quite clearly.

A Tour of the Course

The opening hole as seen on an afternoon day in September

Multiple Trees between first and eighteenth tees green soak in the midday sun. Ahead, two original fairway bunkers to the left of the landing area (see Aerial four) have been removed and replaced by trees.

The Flourtown Course is crowded with hundreds of mature pine trees, the result of wholesale planting of “christmas trees” throughout the course years ago. A favorite planting spot seems to have been next to bunkers such as this one to the left of the first fairway at eighty yards. In 1994 the USGA Turf Advisory Committee visited the Club and noted the course’s “problem with pines” and advocated that they be largely removed. Unfortunately, they largely have not.

The first and seventeenth

If it possible to love someone or something so much that one becomes blind to obvious flaws then in my opinion, this has to be the “Fat Elvis” of golf holes – a situation so ludicrous that it is obvious to anyone except those Club members incapable of seeing fault in their beloved course.

Here Tillinghast created a double green complex with the first green in the foreground and the seventeenth green above and a bit to the right (a very similar set of greens are found at the second and tenth holes). As the first hole plays slightly uphill, this would have created a challenge to the golfer’s depth perception regarding the approach to the first green. Sometime around the 1940-50’s for reasons one can only speculate (the guess here being “framing” and “separation”) a series of small hemlocks was planted directly between the two greens. As we can see, they are not small anymore.

Another view of holes one and seventeen:

‘…we must not have them directly by our putting greens (and) not too close to the line of play’

Unique short game challenges await long on one or right on seventeen.

Third and final view of holes one and seventeen:

The stand of five sixty foot hemlocks steal the morning sun from seventeenth green and the afternoon sun from first green. (this photo was taken at noon).

Hole Two

Stand of four tall pines left of second green.

Left greenside. Apart from robbing sunlight from the greens themselves, the abundance of trees found adjacent to many of the course’s greens result in the unfortunate fact that some of the worst turf conditions to be found on the course are at greenside.

Current view from the championship tee at the fourth.

1938 – Holes seven(left), four (middle) and five (right)

As trees have grown in and encroached on lines of play at the Flourtown course many of the best and most unique design features have been altered or removed.

Tillinghast is widely credited with (some say took credit for) the famed “Hell’s Half Acre” hazard at the par five seventh at Pine Valley. In his writings Tillinghast espoused the idea of the “great hazard” as an optimal means to defend the par five (another fine example survives at Baltimore CC, Five Farms). Here we see Tillinghast’s original fourth at Flourtown – no less than twelve bunkers comprise the Great Hazard designed to require a forced carry second shot.

At left we can see the par five seventh with a series of “church pews” style bunkers at the left landing area and further ahead on the right to punish a poor lay-up or off-line attempt to reach the green in two.

Sadly, all of this dramatic bunkering has been lost as trees have encroached on both holes. Today the holes appear as below:

A solitary bunker at the fourth is all that remains of the former Great Hazard.

Former Church Pews face the unbroken stand of trees that march down the left edge of the seventh fairway and overhang the direct route to the green.

we may play around trees but certainly the only route to a hole must never be over or through them..(and) not too close to the line of play

A double “double hazard” at the par four fifth hole – fairway bunker at 150 yards left.

The fifth green marks the high spot of the land on which holes four through nine are constructed. This is the current vista from the fifth green across the fourth, seventh and ninth fairways.

Hole six was constructed as a short par four of 340 yards with a series of four bunkers down the right side and out-of-bounds to the left. As designed, the player faces a clear choice, 1) risk the boundary on the left to set up a short and more direct approach or, 2) play to the safety of the landing area clearly visible between the second and third bunkers and be faced with a longer approach over the remaining two bunkers. Altogether just an terrific short two-shot hole as designed, in my opinion.

Hole six was constructed as a short par four of 340 yards with a series of four bunkers down the right side and out-of-bounds to the left. As designed, the player faces a clear choice, 1) risk the boundary on the left to set up a short and more direct approach or, 2) play to the safety of the landing area clearly visible between the second and third bunkers and be faced with a longer approach over the remaining two bunkers. Altogether just an terrific short two-shot hole as designed, in my opinion.

However, unchecked tree growth has largely eliminated the intended optimal (i.e. riskier) line off the tee on the left side. Off-site trees have not only encroached on the course but actually overhang the fairway by some five to ten yards.

A stand of large pine trees directly to the right of the last fairway bunker and a giant elm tree directly between the fairway bunker and the green have effectively eliminated the option of playing to the right side of the fairway.

Likewise, as originally designed a pushed drive into the right fairway bunker at 140 yards (the original second bunker) would have resulted in a forced carry from the sand over the final two bunkers. A daunting challenge but recovery was possible by a well-played shot. As the above photo shows the direct line to the flag is now not only over the bunkers but through a forest of pines.

Likewise, as originally designed a pushed drive into the right fairway bunker at 140 yards (the original second bunker) would have resulted in a forced carry from the sand over the final two bunkers. A daunting challenge but recovery was possible by a well-played shot. As the above photo shows the direct line to the flag is now not only over the bunkers but through a forest of pines.

In my opinion such “double hazard” situations as the one above are clear evidence that trees have indeed been planted and/or allowed to grow “too close to the line of play”. Unfortunately, the Club’s response to such situations has generally been either to do nothing or to remove the bunker.

Hole Eight

The condition of the green at the par three eighth hole is a chronic source of concern. Not surprising considering the lack of sunlight due to the numerous mature trees that have been allowed to grow up around and behind the green. Several original Tillinghast bunkers behind the green have been removed, their place taken by large pines.

Large Pines at back right and the large maple overhanging the right greenside bunker combine to rob the green of mid afternoon sunlight. Likewise, the large ash beside the left greenside bunker block the morning sun. The resulting affect on turf conditions is predictable.

In the fall of 2006 the Philadelphia Cricket Club hired XGD Systems to install new drainage on the problematic fifth, eighth and eighteenth holes at the Flourtown course. This is the same firm and technology that was successfully implemented at Oakmont for all of its greens in preparation for the 2007 US Open. As the above photo of the eighth green shows, almost one year after the work was done results have not been good. In my opinion the failure of the project is due to the fact that no trees were removed at any of the three green sites to address the root cause of the problem affecting turf conditions – the lack of adequate sunlight.

Hole Nine

Philadelphia Cricket Club members take particular pride in the closing holes on both the front and back nines of the Flourtown course. The 456 yard uphill par four ninth and 482 yard downhill par four eighteenth have each long been cited in various “best of” lists. Unfortunately very few members have been around long enough to have had the pleasure of experiencing the ninth hole as it was designed to play.

The above photo shows the ninth hole as it appeared in 1938. As at, for example, the first at Prestwick, the entire right side is bordered by a railway (since abandoned) and is out-of-bounds. The twolarge fairway bunkers are clearly positioned so as to provide the player with the risk/reward choice to either, 1) take the direct route up the right side, thereby challenging not only the bunker but the boundary as well, or 2) play left to the safety of the landing area short of the long left bunker. Note that the conservative play will not only necessarily require a longer approach of some 200 yards but brings into play the fairway bunker on the left some fifty yards short of the green.

The above photo shows the ninth hole as it appeared in 1938. As at, for example, the first at Prestwick, the entire right side is bordered by a railway (since abandoned) and is out-of-bounds. The twolarge fairway bunkers are clearly positioned so as to provide the player with the risk/reward choice to either, 1) take the direct route up the right side, thereby challenging not only the bunker but the boundary as well, or 2) play left to the safety of the landing area short of the long left bunker. Note that the conservative play will not only necessarily require a longer approach of some 200 yards but brings into play the fairway bunker on the left some fifty yards short of the green.

Note also even in this old picture the trees that the Club has planted along the right side of the fairway, presumably to provide “separation” from the train tracks.

Hole Nine

1:30pm mid-September

Above is the current view from the member tee at 425 yards. The unbroken line of mature trees which line the entire length of the hole not only block the midday sun, but have effectively eliminated the intended direct route option off the tee along the right side boundary. A draw can no longer be played from this tee box. Likewise, a “perfect ” drive down the right side is no longer a possibility.

Meanwhile, on the left side too many trees planted too close to the fairway result 1) in a double hazard situation with respect to the left fairway bunker, and…

…2) typical turf conditions between the ninth and seventh fairways. Note ahead that further tree-planting continues unabated.

Current view from the ninth green back to tee at midday. As one can imagine, chronic poor turf conditions plague the right side of the fairway.

The eleventh represents another case of too many trees too close to the fairway and too close together whereas the twelfth features adouble hazard created by the mass of trees planted between twelfth and thirteenth fairways from the fairway bunker left of the landing area on the par five twelfth hole.

Another double hazard situation – left fairway bunker at 115 yards.

More “Christmas trees” planted long ago next to bunkers and/or greens. These towering specimens can be found at right greenside on the twelfth hole. Incredibly, up until about five years ago, another of equal size stood between the trees shown above and the greenside bunkers and was only removed after years of discussion at the committee level, ironic when one considers the amount of forethought and discussion which presumably went into the planting of small pines throughout the course fifty or more years ago (I’m guessing “zero”).

The USGA recommendation for the setback of the edge of the canopy for trees is ten yards from tees, fairways, bunkers and greens. At the thirteenth hole the entire left side of the fairway is lined with mature trees (such as the above sycamore at 100 yards) the base of which are just steps from the fairway’s edge.

Note ahead the small tree planted just in the past few years at the corner of the right greenside bunker. We can imagine the effect it will have on sunlight, turf and playing conditions when it reaches the height of the towering elm and sycamore visible just a few steps off of the back of the green at right. When combined with the huge specimens visible beside and behind the left greenside bunker we will finally have this green surrounded.

The fourteenth hole as seen in 1938

Tillinghast executed a dramatic series of bunkers short of the green at the par four fourteenth hole. Sadly, all have been lost.

Current view of the fourteenth green.

The extravagant bunkering short of the green has been replaced with a single long bunker. Meanwhile a motley collection of pines, maples and other nondescript trees has grown in and formed a wall back and around the green.

View from right greenside of the fourteenth.

“we must not have them directly by our putting greens (and) not too close to the line of play’

Guilty on both counts, in my opinion.

View of the fifteenth from the tee

The fifteenth is a par threemeasuring over 200 yards with out-of-bounds the entire length of the right side. As designed, the hole was originally a Redan (aerials one and eight). However, as the trees planted behind the fourteenth green (visible at left) have matured (thus creating the desired tree-lined “bowling alley” effect), the original tee has been replaced with two sets of tees further right and along the boundary while the short cross bunker was removed, thus fundamentally altering the intended playing characteristics of what must have been a truly magnificent hole.

Sadly, the original tee is gone and the intended line of play is now choked with trees.

The sixteenth as seen today. As trees have grown in along the left side, the first fairway bunker on the left has been removed and replaced by a mound. Two other fairway bunkers have also been removed. (Aerial 1).

The remaining fairway bunker left is a clear double hazard.

“we may play around trees but certainly the only route to a hole must never be over or through them…”

Overgrown trees overhang the right fairway bunker.

The seventeenth is a dogleg left par four with fairway bunkering protecting the corner of the doglegand providing a risk/reward tee shot. A shorter fairway bunker (Aerial 1) has been lost and an enormous elm tree overhangs the remaining bunker and fairway beyond.

A stand of mature sycamores which line the left side of the seventeenth fairway have grown to the point that, having successfully challenged the fairway bunker, the player is “rewarded” with this direct line to the green from the left side of the fairway at 160 yards.

At greenside right, the previously discussed towering hemlocks between the seventeenth and first greens await the pushed approach.

More than a year ago, the Club constructed a practice putting green between the eighteenth and first tee the under the shade of a row of mature trees…

…unfortunately, the results have been predictable.

Conclusion

A stated previously, I believe very strongly that the Philadelphia Cricket Club’s Tillingahst course at Flourtown is in desperate need of a comprehensive tree removal program.

Virtually every club privileged enough to be caretakers of a great course from the “Golden Age”, both nationally and in the Philadelphia area, has had to come to grips with dealing with the “tree issue”. While (just as at other clubs) the issue is sure to be an emotional one, I believe the Cricket Club can no longer and should no longer avoid taking the proactive steps necessary to allow this historic and once-great golf course to be great again.

Thanks for taking the time to read this essay. I welcome all comments, support, criticism or suggestions.

Gib Carpenter

e_g_c_2@yahoo.com

The End