Shinnecock Hills Golf Club (Southampton, NY) When you pair arguably the best course in the world with arguably the best clubhouse in the world, you get Shinnecock Hills.

When you pair arguably the best course in the world with arguably the best clubhouse in the world, you get Shinnecock Hills. In 1898, seven years after Shinnecock Hills Golf Club opened but well before its current site was fully developed, the New York journalist Hugh Fitzpatrick penned this timeless sentence in the popular magazine

Outing: "Shinnecock Hills must still be judged the most typical of our seaside links, for its sand dunes, as that devoted golfer, Honorable Henry E. Howland, has said, 'since the resolution of matter from chaos, have been waiting for the spiked shoe of the golfer.'"

Shinnecock means so many different things to so many people that I'm inclined to limit this review to describing my personal affinity for the place. Although I won't (I have too many specific things to say about the course, and this is an architecture site at the end of the day), that is where I'll begin. (Ran's superb profile is available here:

http://golfclubatlas.com/courses-by-country/usa/shinnecock-hills-golf-club-ny-usa/, and a quick search reveals that this discussion board is filled with posts about all aspects of the club and course, including its fascinating history.)

Shinnecock's naturally sandy soil animates a windswept landscape--seen here in the layered bunkering at the 3rd--that is at once rugged and beautiful. Writing for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in July 1935, Ralph Trost observed that "Shinnecock Hills was constructed by the same hands that built famed Pine Valley. In bunkerings and hole designs there is much of Pine Valley suggested in Shinnecock's holes. But Shinnecock is as open as Pine Valley is sheltered, as treeless as the New Jersey course if flanked by pines."

Shinnecock's naturally sandy soil animates a windswept landscape--seen here in the layered bunkering at the 3rd--that is at once rugged and beautiful. Writing for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in July 1935, Ralph Trost observed that "Shinnecock Hills was constructed by the same hands that built famed Pine Valley. In bunkerings and hole designs there is much of Pine Valley suggested in Shinnecock's holes. But Shinnecock is as open as Pine Valley is sheltered, as treeless as the New Jersey course if flanked by pines." For many professionals, Shinnecock is the greatest course in the world, the one Ben Hogan prized as "one of the finest I have ever played" for each hole's "complete definition," where "[y]ou know exactly where to shoot and the distance is easy to read," and the one Tom Lehman heralded as "without question my favorite course in all the world" for representing "true golf, a fair, tough test from one through eighteen, a golf links that ultimately stimulates all the senses." For many reviewers, it is the Muirfield of the United States, the ultimate championship venue blessed with generally accepted characteristics of fairness: straightforwardness and an absence of quirk. For architecture buffs, it is the perfect routing, albeit one with a few too many elevated greens. For historians, it is a pioneer club, not only the oldest organized golf club in the United States but the very first to admit women. For local politicians, it is at the heart of the longstanding dispute--regularly aired in the courts--over the apportionment of land rights between descendants of the English colonists and the Native American tribe after which the club is named.

The perfect clubhouse.

The perfect clubhouse. For me, Shinnecock has been something entirely different. At first, before I played golf, Shinnecock was the rugged, entrancing landscape down the road from The Lobster Inn, a casual seafood joint on Montauk Highway where plastic lobster bibs and a serve-yourself salad bar endlessly delighted me as a child (and, through the tinted lens of nostalgia, still do as an adult). I could drive right through it and admire its beauty, if not the game played on it, but the since-removed white "PRIVATE Members Only" sign on the drive up to the clubhouse reminded me that it was a national park to which I did not have access. When my love for golf grew to match my love for nature, the temptation of Shinnecock often proved hard to resist. Where I once stopped my car to take pictures, I traded my camera for a spare wedge. There was the early spring evening when I dropped an imaginary ball off Tuckahoe Road at the end of the 12th fairway and brushed the impeccable grass--the first swing, if not shot, I had ever taken on a world-class golf course. Years later, I stood next to the gate guarding the gap in the shrubbery behind the 6th green and imagined trying my luck on the famed Redan in the distance, haunted by the images I had seen on TV during the summer of 2004. In my mind's eye, my 7-iron at dusk in the dead of winter was pure, but a foot short. Still, I opened my eyes and smiled: Simulated golf was as close as I was going to get, but standing two feet from the real thing made it much easier to accept.

Shinnecock is the rare course that plays as good as it looks, presenting the perfect meld of conditions--at once flawless on the short grass and rugged outside of it. Keeping it that way, even on a course so natural, requires a lot of work, and Jonathan Jennings, the club's amazing superintendent, and his staff have done that work better than most.

Shinnecock is the rare course that plays as good as it looks, presenting the perfect meld of conditions--at once flawless on the short grass and rugged outside of it. Keeping it that way, even on a course so natural, requires a lot of work, and Jonathan Jennings, the club's amazing superintendent, and his staff have done that work better than most.My friends got wind of my fascination with the course, too. The next year, one found two items of Shinnecock paraphernalia for sale online: a hat with a simple, if blocky, "S," and a pullover with the full logo. That they were both fully burgundy--and therefore likely not official Shinnecock merchandise--didn't stop me from wearing them whenever I could. To this day, the former remains in my golf-hat rota. More recently, another friend arranged a lesson with the head professional as a birthday present; in addition to hitting balls on the range, I would finally have the chance to legitimately play at least a few holes. Or so I managed, without any basis but my dreams, to convince myself. From the back of the range, we made our way instead to the practice bunker by the pro shop. Several shots later, including one thinned somewhere in the direction of the tree-hidden maintenance complex, I was on my way home. I had learned multiple game-changing tips that I continue to use to this day, but I was no holes richer.

Shinnecock's 16th, with its surrounding fields of gold, is rightfully on the short list of best and most beautiful par-5s on the planet.

Shinnecock's 16th, with its surrounding fields of gold, is rightfully on the short list of best and most beautiful par-5s on the planet. For me, in short, Shinnecock has long been a forbidden fruit. I had nibbled the rind, but never tasted the fleshy inside. That all changed this summer, when the stars aligned and I finally had the opportunity to play my holy golfing grail, to experience my white whale. "Worth it" doesn't even begin to describe my 35-year wait's true value.

The final green sits perfectly within its surrounding landforms, emblematic of the "found" quality of many of Shinnecock's holes. The Clubhouse

The final green sits perfectly within its surrounding landforms, emblematic of the "found" quality of many of Shinnecock's holes. The Clubhouse  Even from the locker room, the views are stunning.

Even from the locker room, the views are stunning. Few buildings marry function with form as well as Stanford White's clubhouse at Shinnecock. Surrounded on all sides by golf--the practice putting green guards the south face, the 9th green the north face, the 1st tee the west face, and the 10th tee the east face--it is ideally situated. The interior is open, light, and airy, even though air conditioning is not, and never has been, one of the amenities. Apart from the red carpet, everything in the locker room is white, accented only by the history that seeps out of every pore. And, of course, by the views, which are everywhere you look and framed perfectly by the rustic, single-paned, always-open windows. A meal and a drink on the veranda--ideally in that order, the former before the round, the latter after it--removes the framing and previews or reminds of the sensation of being one with golf's most glorious, uncluttered landscape. From the course, the clubhouse functions much like the windmill next door at National Golf Links of America in tying the landscape together--and, as a literal house on a hill, lends an aspirational element to the entire round, as it is in view from each and every hole of the course.

Stanford White's low-profile 1892 clubhouse lords, in the most benign way possible, over Shinnecock's hills.

Stanford White's low-profile 1892 clubhouse lords, in the most benign way possible, over Shinnecock's hills.  The windows, rightly everywhere, are permanent frames of golf's most compelling landscape.

The windows, rightly everywhere, are permanent frames of golf's most compelling landscape.  Golf surrounds all sides of the clubhouse. The east side affords views of the glorious tee shot at the 10th.

Golf surrounds all sides of the clubhouse. The east side affords views of the glorious tee shot at the 10th.  Like its windows, the clubhouse's columns provide ready-made frames for pictures.The (Greatest) Golf Course (in the World)

Like its windows, the clubhouse's columns provide ready-made frames for pictures.The (Greatest) Golf Course (in the World)

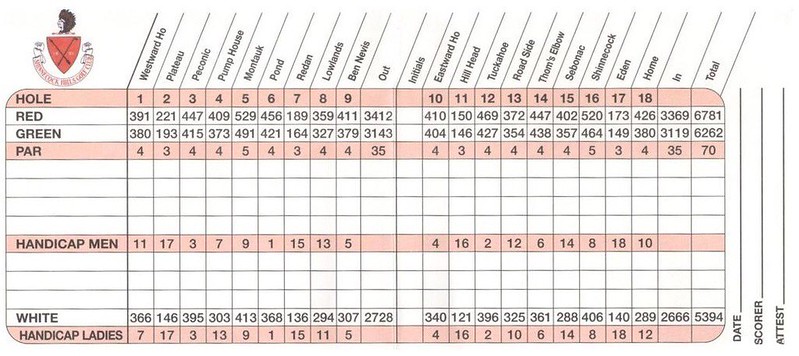

Even from the championship tees (not reflected in the above scorecard, but currently listed at 7,041 yards), Shinnecock is a "short" course by modern standards, proving that length is only one way to challenge the best.

Even from the championship tees (not reflected in the above scorecard, but currently listed at 7,041 yards), Shinnecock is a "short" course by modern standards, proving that length is only one way to challenge the best. Noted architect Dana Fry once said, in words I wholeheartedly espouse, that "Shinnecock Hills simply has no weakness. It is as pure as a routing plan can get and a remarkable golf course in virtually every way." Without ever feeling disjointed, the routing is as varied as you could want, although slightly favoring the left-to-right hitter, as more than twice as many long holes move in that direction. At the routing's core are two hallmarks of William Flynn's work: the two-loops, as opposed to the out-and-back, approach (one of several reasons the Shinnecock-Muirfield comparison often gets made), and the use of triangulation within each loop. Together, these features account for the much-heralded variety in the wind directions encountered during a single round at Shinnecock. The front-nine loop occupies the western half of the property, while the back-nine loop occupies the eastern half--the left and right sides, respectively, of the aerial photograph below. For more on the within-loop triangulation at Shinnecock, see Ran's 2011 feature interview with Wayne Morrison and Tom Paul, who use colorized versions of Flynn's original sketches to discuss the routing at length:

http://golfclubatlas.com/feature-interview/wayne-morrison-april-2011-2/.

From above, you can see why Shinnecock's routing is considered the best in the world. Credit: Google Earth. Hole 1 ("Westward Ho"): Par 4, 391 yards

From above, you can see why Shinnecock's routing is considered the best in the world. Credit: Google Earth. Hole 1 ("Westward Ho"): Par 4, 391 yards Long heralded as one of the best opening tee shots in golf, Shinnecock's first--from which each of the front nine's other holes, as well as several on the back, is visible--previews much of what is to come: elevated tees, generous, gently doglegged fairways protected at their corners (typically the inside) by bunkers, and raised, lightning-fast greens with falloffs of varying severity at the back edge. The bunkers along the right side of the opening fairway are representative of their strategic placement throughout the course: Short or long yields ample fairway--refreshingly, the bunkers are not merely hazards in the already-hazardous rough--but because accurate knowledge of one's length off the tee is rare, especially on a layout as exposed to the wind as Shinnecock, the task in avoiding them is not quite so straightforward.

A gettable hole, if only the golfer could ignore his nerves and the landscape around him.

A gettable hole, if only the golfer could ignore his nerves and the landscape around him.  Like an unmooring, departing the clubhouse from Shinnecock's first tee feels every bit the start of a journey that it is.

Like an unmooring, departing the clubhouse from Shinnecock's first tee feels every bit the start of a journey that it is.  Recently tweaked by Coore & Crenshaw, the bunkering at Shinnecock has a rugged appeal befitting the terrain.

Recently tweaked by Coore & Crenshaw, the bunkering at Shinnecock has a rugged appeal befitting the terrain.  Right from the start, the golfer realizes that long--down one of Shinnecock's severe falloffs--is dead.

Right from the start, the golfer realizes that long--down one of Shinnecock's severe falloffs--is dead.  But the golfer can take some solace in the vastness of the falloffs, as all but a true screamer will remain on the short grass. Hole 2 ("Plateau"): Par 3, 221 yards

But the golfer can take some solace in the vastness of the falloffs, as all but a true screamer will remain on the short grass. Hole 2 ("Plateau"): Par 3, 221 yards Shinnecock's longest par-3, the second plays straight uphill to a relatively large green. Although it, too, falls off at the very back, its depth is adequate to reward even low long-iron shots. A set of terraced bunkers, a common occurrence at Shinnecock, guards the green short and left. Their placement is not only beautiful--emblematic of Shinnecock's rugged aesthetic--but strategic, as many a golfer will try to overcome the hole's length by overswinging and, inevitably, pulling the ball.

A daunting, if beautiful, view from the tee.

A daunting, if beautiful, view from the tee.  Shinnecock's first set of terraced bunkers--to me, a fairer hazard than one large bunker--comes at the second.

Shinnecock's first set of terraced bunkers--to me, a fairer hazard than one large bunker--comes at the second.  The shorter the tee shot, the lower you are on the terrace and the steeper and more difficult the approach.

The shorter the tee shot, the lower you are on the terrace and the steeper and more difficult the approach.  Though large, the green has numerous contours and another, albeit more gradual, falloff at the back to keep putters wary. Hole 3 ("Peconic"): Par 4, 447 yards

Though large, the green has numerous contours and another, albeit more gradual, falloff at the back to keep putters wary. Hole 3 ("Peconic"): Par 4, 447 yards A reminder that Shinnecock, despite its fearsome reputation, is actually quite playable for the average golfer, the third hole plays from another elevated tee to a massive fairway. Another set of terraced bunkers menacingly guards the fairway's beginning, although they are less actual hazards than sources of visual intimidation. The approach plays back uphill to a wide, open-front green pitched sharply from back to front, with a small shelf in the top/back-right corner. Where Shinnecock allows for a run-up shot, it is quite often the ideal one; the golfer should follow the architecture and embrace the opportunity.

Although visually intimidating, the terraced bunkers short of the 3rd fairway facilitate aiming on one of Shinnecock's few slightly blind tee shots.

Although visually intimidating, the terraced bunkers short of the 3rd fairway facilitate aiming on one of Shinnecock's few slightly blind tee shots.  Even on the front nine's less dramatic terrain, Shinnecock's hills--here seen looking back up the 3rd fairway--influence play.

Even on the front nine's less dramatic terrain, Shinnecock's hills--here seen looking back up the 3rd fairway--influence play.  A view toward the 3rd green from the bunker guarding the right side of the 7th green reveals the wisdom of a low, running approach. Hole 4 ("Pump House"): Par 4, 409 yards

A view toward the 3rd green from the bunker guarding the right side of the 7th green reveals the wisdom of a low, running approach. Hole 4 ("Pump House"): Par 4, 409 yards A gentle dogleg-right par-4, the 4th gets its name from the small structures guarding its right side. Although a wide fairway unfolds straight ahead of the tee, the prevailing wind--and the temptation to hit the fairway's right side for a shorter approach to a well-protected green with falloffs at all sides--makes the tall grass surrounding the pump houses a magnet for imprecisely hit balls.

Often overlooked, the 4th offers a view that is impossible to overlook.

Often overlooked, the 4th offers a view that is impossible to overlook.  Perched and well bunkered, albeit with an opening for the ground game, describes many of Shinnecock's greens, including this one at the 4th.

Perched and well bunkered, albeit with an opening for the ground game, describes many of Shinnecock's greens, including this one at the 4th.  Although many of Shinnecock's greens fall off severely at the back, they usually fall into open space, allowing balls to be found and shots to be played. Hole 5 ("Montauk"): Par 5, 529 yards

Although many of Shinnecock's greens fall off severely at the back, they usually fall into open space, allowing balls to be found and shots to be played. Hole 5 ("Montauk"): Par 5, 529 yards The site of my first eagle in 10 years, the 5th is a visually unremarkable par-5. After a drive to a wide fairway bisected early by bunkers, the hole turns slightly right--the doglegs at Shinnecock, and there are many, are refreshingly gentle--to another open-front green with a falloff at the back. The hole's length and design features make going for the green in two shots a realistic possibility for a good percentage of golfers hitting the fairway with a solid tee shot. What assists with overcoming the distance needed to reach the green is an ingenious speed slot on the left side of the fairway approximately 100 yards from the green. Hitting it with a hard, low fade can propel the ball--as it did in my case--the rest of the way home, even if, by yardage, the target seems well out of reach.

A shot left of--or, ideally, over--the right-hand fairways bunkers leaves the most margin for error.

A shot left of--or, ideally, over--the right-hand fairways bunkers leaves the most margin for error.  The banked left side of the end of the 5th fairway serves as a speed slot for those trying to reach the green in two.

The banked left side of the end of the 5th fairway serves as a speed slot for those trying to reach the green in two.  The gently domed fifth is typical of Shinnecock's greens: visually benign, actually devilish. Hole 6 ("Pond"): Par 4, 456 yards

The gently domed fifth is typical of Shinnecock's greens: visually benign, actually devilish. Hole 6 ("Pond"): Par 4, 456 yards Historically the hardest hole at Shinnecock--and an homage to the famous "Channel" hole at Lido--the long par-4 sixth, despite being routed across relatively flat land, plays blind from the tee to a wild split fairway with sandy waste areas aplenty, especially along the right side. (These waste areas were recently restored by Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, who have been doing work on the entire course in preparation for the 2018 U.S. Open. Because I had never before played the course, I am unfortunately unable to evaluate their work--except to say that everything looks ideal.) The approach is no bargain either, as the course's sole water hazard, the hole's eponymous pond, must be carried with what is often a long iron or hybrid. Out of bounds guards the entire right side of the hole.

The newly restored sandy areas at the 6th hole fit perfectly with Shinnecock's landscape.

The newly restored sandy areas at the 6th hole fit perfectly with Shinnecock's landscape.  A deep green, viewed here from behind, receives approach shots inevitably struck with long irons or fairway metals.

A deep green, viewed here from behind, receives approach shots inevitably struck with long irons or fairway metals.  At the intersection of the 4th and 7th tees, the view back down the 6th reveals its serpentine, split-fairway nature.

At the intersection of the 4th and 7th tees, the view back down the 6th reveals its serpentine, split-fairway nature.