A while back I asked the question as to why golf took off in the 1920's in the small towns of the Midwest. Why were seemingly rural farming outposts in states like Kansas all of a sudden rushing to build golf courses?

I suspect part of this had to do with the coverage the game was receiving in the press. Certainly Francis Ouimet's victory at Brookline had vaulted the popularity of the game across the nation, and the papers started covering local matches with as much fervor as they covered the crop reports. National columnists like Grantland Rice (an example of his work on the growth of the game in the south below) were picked up by papers across the country, and towns without courses all of a sudden felt like they needed one.

Nov. 25, 1916 Scranton Republican -

In addition, the popularity of the automobile allowed for a courses to be built away from the center of town. This often allowed for the utilization of less expensive land, and increased the area from which the membership or clientele could be drawn.

Oct. 23, 1920 Washington Times -

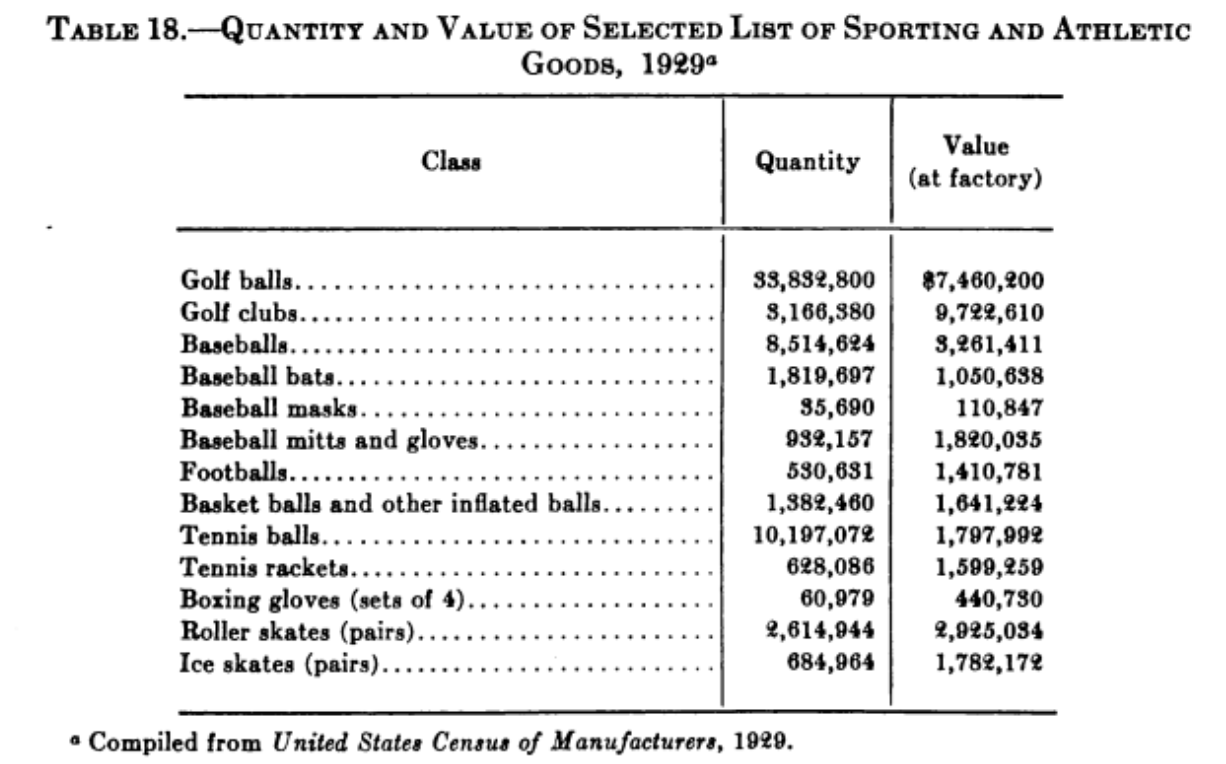

Sitting in the background were the equipment manufacturers. The growth of golf in this country has always gone hand in hand with the various sporting goods houses and course building entities that sought to expand the game in a symbiotic pursuit. The following chart from 1929 gives us a good idea as to just how big the golf business was compared to other sports.

It is around the early 1920's that golf truly became a game of the people. Tom Bendelow's 20-year seemingly Quixotic attempts to promote municipal golf had reached a tipping point, and courses were being built for the use of the common man across the country. Small towns that couldn't afford a large scale private club were organizing quasi-municipal clubs, courses built on a budget, open to all and without any meaningful financial barriers to entry.

As hinted at by other architects, there was almost too much work to be covered. Certainly even Bendelow didn't have the means to lay down plans for the thousands of courses that would be built between 1920 and 1925.

Local pros were jumping in on the design game, and the likes of Perry Maxwell, John Bredemus, William Dalgleish, Bill Diddel and a number of other regional experts saw their design careers take off.

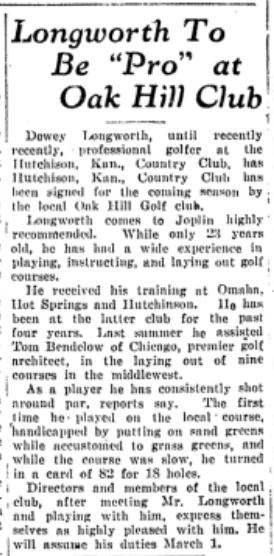

One such opportunist was a young local Kansas professional named Dewey Longworth. A quick search on this site reveals two results for Longworth, dealing with his later connections to Tillinghast while he was the professional at Claremont CC (from 1928 to 1960) and the President of the Northern California PGA. Looking for design attributions is almost just as futile, as there are only three courses in Kansas listed under his name.

My best guess is that Longworth was recruited by Tom Bendelow to serve as a representative for American Park Builders in Kansas. There are a few article from 1922 noting an association between the two, and this type of regional outsourcing would make sense.

Longworth, his brother Ted (who had an interesting career of his own) and guys like Arthur Bonebrake served as the ambassodors of golf in Kansas. When a course was opened in the middle or western part of the state, it was a variation of those names that played in the first foursome putting on an exhibition of how golf should be played. Longworth worked for several clubs in the state as their professional, seemingly bouncing to the next location once he had succeeded in getting the game to take root. Along the way he laid out courses in towns like Liberal, Dodge City, Larned, Ellis, Lyons, Fort Hays, Lakin, Salina and Eldorado. I suspect there were others, as the number of courses built in Kansas during the early 1920's is remarkable, and most of these courses are still right there were dirt was first scraped for the layout of fairways and sand greens.

In 1922 he moved to Joplin, Missouri to work at the Oak Hill GC. While there he laid out the Schifferdecker Municipal course in town, as well as a course in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

Although his design career was fairly short-lived, it serves as a perfect example of how the game was spread to the small towns across the country. Longworth eventually chose the life of a club professional, and seemingly was well suited for this role as he was included in the various lists of Top Professionals across the country. But for a short period of time in the early part of the Golden Age, the over-looked Dewey Longworth filled as important a role (albeit smaller) in the growth of the game, and the business of golf, as any of the names that have become synonymous with golf course design.