The Valley Club at Montecito

CA, USA

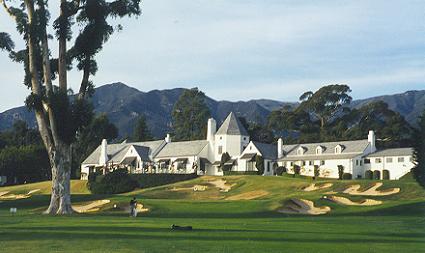

The charm of The Valley Club is evident to anyone on the 14th tee.

Alister MacKenzie fully deserves the recognition that his design work at The Valley Club of Montecito has consistently garnered for 70 years. All the greats from Hogan to Player to Woods have spoke of its delights. However, given the unanimous praise from both club members to the most accomplished golfers, what the authors find most curious is that no architect builds such a style course today. The Valley Club seems to the authors to be the subtlest course that Mackenzie designed. His other work frequently features dramatic features, be it the greens at Pasatiempo or Crystal Downs, or the enormous scale of the West Course at Royal Melbourne and Augusta National, or MacKenzie’s wildly artistic (originally at least) bunkers at Cypress Point. Such extravagant features would seem out of place here in the intimate environs of Montecito.

The inspired approach shot into the 3rd green.

While MacKenzie gets credit for the design of The Valley Club, Robert Hunter deserves similar recognition for the construction of the course and indeed by extension, some of the subtlety that makes the course so alluring. The authors contend that Hunter’s on-site presence during construction and long time participation at The Valley Club accounts for a lot of the subtle sophistication that is present at The Valley Club to this day. The Valley Club can appear deceptively pleasant, as it gets off to an easy start with a pair of reachable three-shotters. Yet, as the golfer gets closer to the green, more and more can he find himself in an unenviable position. Above the hole on 3 and 5, short right of the hole on 7, long on 8, etc. the list goes on and on. The golfer may not realize the difficulties of his situation until it is too late and yet another shot slips away.

The idyllic 4th can surprise the unwary golfer.

Take the 4th hole as example. This idyllic one shotter is 146 yards and plays downhill at that. The green is surrounded by lovely sycamores and is the very picture of serenity. And yet ¦four bunkers surround the long green, the back half of which actually slopes away from the unsuspecting golfer. The shoulder of these bunkers makes a recovery shot to a short-sided hole location highly unlikely. Also, the sea breezes may not be felt in the enclosed tee area but can play havoc with the lofted approach shot. In many ways, this hole summarizes The Valley Club: charming and peaceful but requiring sound execution and thought. Such green complexes are in stark contrast to most being built today. Too few developers would appreciate their intricate nature, fearing perhaps that their new course might not be flashy enough to draw attention. How sad and the resulting three-leveled, tortured contraptions that serve as greens at some of these new courses are completely disjointed from their natural surrounds.

The right to left sloping 16th green is beautifully integrated into its surrounds.

Gone are the days where green sites take time to understand and are worth studying. The man who penned The Links in 1926 clearly understood many of these principles and MacKenzie, in a moment of rare modesty, described Hunter’s The Links as ‘the best book on golf literature ever written.’ Still, subtle features have a way of being lost through time and The Valley Club is actually better off today than it was a decade ago. The reason is that the Club carefully undertook a project being in the mid-1990’s to restore many of its original, more subtle playing features. Tom Doak at Renaissance Golf Design brought back the subtleties around the green complexes by demonstrating that these areas were intended to be closely mown. Whereas rough had encroached on many of the greens, today the golfer is given a multitude of options with tight chipping areas. The 13th green with its shaven bank that falls away to the right is a perfect example. Instead of having a straightforward pitch shot from the rough, the golfer is now faced with a full range of options from a bump-and-run to a flop shot. Whichever way he selects, the resulting shot requires greater skill and is of more interest than from the same spot five years ago. Maximizing the intricacies of the land best occurs during construction and this is where Hunter shined. However, much of this subtlety had been buried underneath the rough for years. No more. Furthermore, thanks in particular to Jim Urbina, MacKenzie’s scare bunkering has been handsomely restored, highlighted behind such greens as the 3rd and 15th.

The recently restored irregular shaped bunkers behind the 15th green.

In addition to the subtleties around the greens, the course routing is also full of deception. I thought I was downhill on 11? Surely 14? No, alas, the tees and greens are virtually level and players are forever coming up short on these one shotters. Hitting in the practice area beside the 18th fairway, the golfer clearly is aware he is hitting down a slope. However, coming back up the hill while playing the 18th, the golfer doesn’t perceive he is nearly as much uphill as he was practicing downhill. The same applies with the 15th hole whose cross bunkers see much more business than would normally be the case for bunkers at the 400 yard mark. Perhaps the reason that today’s architects do not replicate the style of The Valley Club is that the property here is of such unusual excellence that it would be hard to build a course of similar quality? Not really. Yes, The Valley Club possesses natural golf country away from the clubhouse on the other side of Sheffield Drive. The terrain is dotted with stately oaks and sycamores with Picay Creek winding its way throughout and MacKenzie made the most of it by creating original holes of great pleasure to both walk and play. However, MacKenzie and Hunter were stuck with less than ideal golf land on the clubhouse (but what a clubhouse!) side of the property – a gentle, broad slope with no distinguishing characteristics. Yet the strategy that Mackenzie created in these final four holes is some of his most impressive work and remains a great testament to his skill. The fact that Mackenzie got the design right is of little surprise. After all, The Valley Club opened in 1929, the year after Cypress Point and the same year as Augusta National. MacKenzie was clearly in top form. The Valley Club has stood Harry Colt’s test of time theory and it remains as close to the original design as any MacKenzie course. When MacKenzie presented Cypress Point Club with a (some one say the) book on architecture by Wethered and Simpson, he scribbled in the margin, ‘A golf course that is altered is an indication of a faulty design.’ While that comment applies to Cypress Point, it more accurately applies to The Valley Club, given that 30 of the 125 bunkers from the original Cypress Point layout have been eliminated. To do a Holes to Note Section is to miss the point of The Valley Club. The whole is greater than the parts and it is the continuum of varied holes that roll across the property that distinguish this course. Finally, it should be noted that the Club (1) doesn’t believe in yardage markers and, (2) the course embodies point thirteen in MacKenzie’s ideal features for a golf course, namely that a ‘course should be equally good during winter and summer.’ Yes, this subtle course has it all. Shouldn’t more like it be built?

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)