Pinehurst No. 2

North Carolina, USA

Pinehurst’s sandy soil and Donald Ross’s design genius are once again fully evident at Pinehurst No.2.

The design of The Old Course at St. Andrews is exemplary on many levels. Most importantly, it possesses a slew of world class holes that few courses match while remaining fun for a wide range of players. No wonder Charles Blair Macdonald routinely copied more holes from this course than any other, as it possesses that elusive design quality enabling a grandfather, father, mother and their son to equally enjoy its challenges (even the day after hosting a grand event). Though some of America’s greatest courses like Oakmont and Merion have design elements of The Old Course laced within them, playing them after they have hosted a significant event would be quite inhospitable! One course stands out on the American golf landscape for its ability to challenge the very best and yet provide maximum fun to a wide range of players. That course is Pinehurst No.2 and it is no coincidence that it was designed by the Scot Donald Ross who was intimately familiar with The Old Course.

Thanks to the successful restoration project completed by Coore & Crenshaw in 2011, Pinehurst No.2’s design attributes have been reestablished making it unique with The Old Course. Both designs hinge on great expanses of short grass – and the challenge it presents – and by greens that shed balls into swales, hollows and other places unintended by the golfer. Fifty yard plus wide fairways once again greet the golfer on every tee at No.2. Gone is the bermuda rough that choked the fairways to thin ribbons. In fact, there is no rough on the entire course, bermuda or otherwise. There are only two heights of grass, one on the greens and the other everywhere else. Hunting with your head down, searching for an errant drive in bermuda rough, is a thing of the past as are 650 (!) sprinkler heads.

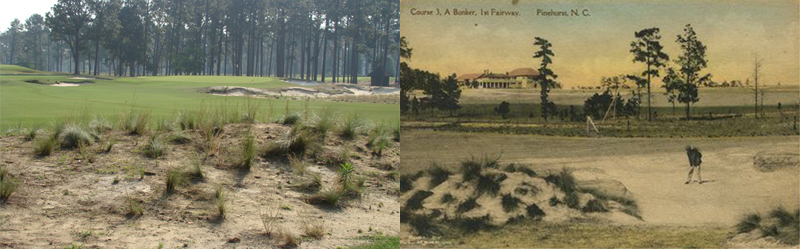

The intended consequence of Coore & Crenshaw removal of thirty-five acres of bermuda rough is that Pinehurst’s sandy floor once again shines through with No. 2 properly reflecting its environs of the Sandhills of Moore County. Predominantly found along coastlines, Pinehurst’s sandy soil is its ultimate trump card over virtually every inland course in America. Reinstating the course’s natural sandy qualities, rather than burying them beneath acres of bermuda rough, was a key objective to Coore & Crenshaw’s successful restoration project. Given that about 85% of the world’s top twenty-five courses are built on sand, overstating its virtues is impossible.

Much like The Old Course, the rub for the good player at No. 2 is to maintain control of his ball. On a soft, receptive course, he plays point to point golf with more precision and confidence, making low scores a distinct possibility. Once the tiger ceases to be able to control the fate of his ball as it scuttles along fast running short grass, worry creeps in, followed by doubt. At this point, the course gains the upper hand.

Not seen for several decades, tee balls are now bouncing three to five yards in the air after landing in the fairway. They run out and 1) stay in the broad fairways, or 2) come to rest in one of the bunkers that protrude into the fairways (and as there is no rough to impede the ball’s progress, the bunkers play larger than their actual foot print), or 3) end up on the native sandy floor strewn with beach grasses, pine straw, etc. where the golfer may or may not draw a good lie. These same scenarios play out at The Old Course where the threat of heather is replaced by wire grass at Pinehurst.

The eye naturally gravitates to the sandy environs but the thin line down the thirteenth fairway marks the fast fading evidence of the new centerline irrigation system. Instead of having 1,100 sprinkler heads to water virtually every spot, No.2 now has 450 irrigation heads that irrigate only the playing surfaces.

The benefit of centerline irrigation is that the fairway edges are becoming molten in appearance, which provides the perfect gradual transition to the sandy areas.

Thirty-five acres of bermuda rough were removed and the native sandy floor was re-established. Sometimes you’ll draw a good lie and sometimes not!

At the green complexes, the common denominator of The Old Course and No.2 is the short grass that surrounds the greens. The putting surfaces themselves couldn’t be more different as St. Andrews’s massive double greens average over 14,000 square feet while Pinehurst’s famous turtleback greens are only 5,500 square feet. More than half of the technical green space is not cupable at Pinehurst given how they slope off on all sides, thereby leaving targets in the 2,500 square foot range. That’s less than Pebble Beach’s notoriously tiny greens. Yet, the key at both courses is how well you get down in two from ten or twenty or thirty yards from the hole. You’ll likely be on short grass but how do you coax the ball near the hole? You might hit a bump and run into the green’s bank, try a pitch shot or even putt from a long distance. The important thing at both courses is that all options are available and that they are within the physical ability of the vast majority who play the sport. Only a professional can gouge a ball from thick rough while controlling the clubface; that dull challenge doesn’t factor into a game at Pinehurst. Creativity and imagination rule the day here, just as Ross intended.

Despite Ross’s constant adaptation of No.2 to changes in technology and agronomy, the course feels homogeneous and unforced upon the landscape. While No.2 may not compete for grandeur with Pine Valley or Sand Hills or for scenic glory with Cypress Point or Royal Portrush , it nonetheless attracts equally ardent admirers. As Tommy Armour eloquently wrote, ‘The man who doesn’t feel emotionally stirred when he golfs at Pinehurst beneath those clear blue skies and with the pine fragrance in his nostrils is one who should be ruled out of golf for live. It’s the kind of course that gets into the blood of an old trooper.’ Ross himself wrote, and his quote is on a sign by the first tee, ‘I sincerely believe this course to be the fairest test of championship golf that I have ever designed. It is obviously the function of the championship course to present the competitors with a variety of problems that will test every type of shot which a golfer of championship quality should be qualified to play. Thus, it should call for long and accurate tee shots, accurate iron play, precise handling of the short game and, finally, consistent putting.’

As we will see, No.2 accomplishes this with a string of exceptional holes which invite comparison on a hole by hole basis to any course in the world.

Holes to Note

(Please note: Two yardages are given, one from the back markers reserved for events like the U.S. Open and another in the 6,300 yard range.)

First hole, 405/375 yards; The first hole perfectly captures the essence of No. 2 as a wide fairway meanders through a broad corridor of pine trees and ends at a sophisticated green complex. What may not be readily evident are the intriguing angles of play. While the first green is forty yards long, it is only half as wide. Its axis runs from front right to back left and points to the right side of the fairway. For the good player, the target area in the fifty yard wide fairway is shrunk by half as he dearly wants to play his approach down the green’s spine. The less ambitious golfer is just pleased to hit the broad fairway. If the approach doesn’t hold the green, one is likely left with a recovery from short grass and ends up with no worse than a bogey. Most first time visitors will fall under the charm of such a course that tests the best while allowing them to muddle through the round with only one ball. Meanwhile, better players recognize the hard edge of the subtle though exacting challenge. Some players during the year end PGA event in 1991 and 1992 went so far to say that No.2 was the hardest course that they had ever played. They see it as Pete Dye does who once remarked to Tom Doak, ‘On the first hole, you’ve got a five foot deep bunker with an almost vertical face to the left of the green, and a humpback green with a bunch of severe dips in the ground to the right of it. What’s so subtle about that?’

As seen from the fairway’s left edge, this approach angle is disadvantageous because the green is set at an oblique angle. The deep left greenside bunker to which Dye refers is evident above.

As seen from the right, the approach is more friendly with the golfer looking down the full length of the green. The sight of so much short short grass to the right of the green is comforting to the less skilled golfer.

And so it begins! The golfer has missed his approach right of the green and now has what is likely to be the first of many ticklish recoveries that he will confront. Importantly, all options are open as to how he plays the shot.

Second hole, 505/410 yards; Tom Watson considers this one of the best second holes in the world, and he is not alone. To achieve so much character on essentially flat land is an amazing design accomplishment and one wonders why this green complex has never been emulated elsewhere on sandy soil. Local golf course architect Richard Mandell has had plenty of opportunity to study No.2 and says in admiration, ‘What I like about the greens at No. 2 is the way Ross doesn’t just simply open up the putting surface to the middle of the fairway or even to the same spot on each golf hole. He constantly mixes it. For example, the best angle to approach the putting surface of the second green is the far left side of the fairway. A golfer’s instinct is to take the shorter route to gain an advantage and that is the right side in this case. It will take the golfer fifty tries to realize the shorter route is the wrong side to approach the green from. When people talk about the subtleties of No. 2, that is a perfect example: Beating your head against the wall multiple times to figure out that isn’t the way to play a certain shot.’

The second green opens up from the left side of the fairway which is exactly where Coore & Crenshaw recaptured Ross’s bunkering scheme. Restoring width to the fairways allows the good golfer to aim for one side or the other in order to gain the preferred angle to certain hole locations. Hence, No.2 has been returned as Ross’s strategic masterpiece.

Ross pushed up the fantastic second green from its surrounds. Its height and challenge are evident when measured against the golfer in the foreground. Less obvious (but well illustrated above) are the one and two foot random fairway ripples that come from working with sandy soil. If the soil was clay, the sunken flat area would quickly become soft and mushy after any rain storm.

This view from behind the angled second green demonstrates how Ross created angles of play at No.2 and how the greens influence decisions off the tee.

Third hole, 390/330 yards; The third is a rare example of a hole being improved by hosting a major tournament. Several large pines were removed from behind the green to make room for grandstands during the 1999 U.S. Open. With nothing to assist with depth perception, the severely sloped back to front green is an even more terrifying target. Of course, gains in technology enable the modern professional to have a crack at the green from the tee when the hole is played in the 340 yard range. The USGA will certainly utilize a forward set for one or two days during the upcoming 2014 U.S. Opens to goad golfers into risking a bogey or worse for a chance at a birdie or better. The left greenside bunker isn’t a bad place to miss as the green slopes toward the golfer and a recovery is easier from here than over the 5,050 square foot green from where the putting surfaces races away. Again, Mandell notes, ‘Another example of Ross’s subtle approach to green design is that most often the best place to miss it is on the bunker side because the putting surface contours are more receptive to a recovery from that side. While instinct says ignore sand at all costs, that is frequently the lesser of two evils at No.2. Of course, these examples of subtlety only come about from years of refinement. Ross had that luxury as his home is in plain sight from the third green.’

… a nervy pitch to a small green sharply tilted from back to front. Anything long is sure death.

Fourth hole, 570/470 yards; In marked contrast to the first three holes, the fourth features attractive land movement with the fairway some forty feet below the level of the tee. Played through a secluded valley, the fourth feels like a different piece of the property and it is as the fourth and fifth holes were once part of the ‘Employees’ Course.’ Built in 1928 by Ross, these nine holes represented affordable golf for the locals but the timing was poor. The Great Depression hit the following year and the Pinehurst Resort was soon under terrible financial strain. The Employees’ Course was shut setting the stage for its first and ninth holes to become today’s fourth and fifth when Ross undertook a major remodel in 1935. Ross was always impressed by the scenic qualities of this portion of the property. The addition of these holes and their sloping land add great variety to No.2.

This long view from the fourth tee captures the valley in which Ross situated the fairway. The day’s far left hole location means that the flag isn’t visible from the tee which is a rarity for No. 2.

Fifth hole, 475/425 yards; When this hole opened as the 445 yard ninth on the Employees’ Course, hickory golf was the norm and it played as a par five. Nothing has really changed! Yes, it was labeled a par four in the 1930s while Ross was alive but many more fives than fours are carded here, so much so to that some consider it the most difficult two shot hole in American golf. The player can’t see where his tee ball finishes but the line off the tee is less a problem than the resulting fairway stance as the ball sits above a right handed player. From this hook stance, the player must flight the ball some 200 yards to a green featuring a steep false front, a false side and a savage left greenside bunker. Nothing within seven paces of the perimeter of the green allows for a cup, such is the manner in which this green slopes away on all sides. The statistics on this green are fascinating as it only features 1,976 square feet of putting surface with a slope less than 3%. Another 896 square feet of green is between 3% and 4% and might be cup-able under certain (i.e. non-U.S. Open) conditions. The remaining 2,925 square feet of the green features slopes greater than 4%. From well back in the fairway, the target area is minuscule at ~2,900 square feet. While it is rare to find a hole this difficult without water, this most challenging approach is mitigated by the reinstated firm conditions which allow for a run up. Unlike less artfully crafted courses, there is a reasonable bail out area short and right, providing lots of ways to card a five with dignity.

The long journey begins by carrying a short bunker attractively cut into the brow of the hill some 150 yards from the middle tees.

The hill and short bunker off the tee hide the wide fairway and the golfer is reliant on his caddie to provide him the correct line to avoid finding the largest waste area on the course.

Though a beast, the fifth provides options with many golfers electing to hit their second shot to the right and treating this hole as the par five that it once was.

During the 2008 U.S. Amateur, Pinehurst No. 2 featured lots of green grass in the form of narrow fairways and wall to wall bermuda rough. Give owner Bob Dedman credit for calling in Coore & Crenshaw to restore the rough edged look and rustic flavor that Ross and Frank Maples carefully cultivated. (Photograph courtesy of Tufts Archives).

Sixth hole, 225/180 yards; Even as late as the 1910s, the No. 2 course wasn’t acknowledged as the best course at the resort as many considered No. 3 to be superior. At that time, No. 2 was very much in an evolutionary process that lasted over thirty years resulting in the layout we see today. Ross first expanded it to eighteen holes in 1908 to accommodate the boon in winter golf. Then No.2 received a big boost when Ross replaced two holes elsewhere with the third and sixth holes in 1923. The third requires finessee while the long one shot sixth calls for some sort of long iron to a green set on a diagonal along a front left bunker and swale. Like Oakmont and National Golf Links of America, Pinehurst No. 2 took several decades to obtain its final level of refinement and excellence. The location of Ross’s own home only a scant 150 yards from the sixth tee meant that Ross himself oversaw all major course developements, from transitioning sand to grass greens to moving the course from the era of hickory to steel shafts. We aren’t left to wonder what Ross would have done as he did it!

Even the mighty West Course at Winged Foot might not have two back to back green complexes as severe as the fifth and sixth at No.2. Parring these two holes consecutively is a life-renewing experience! Sadly, such was not the case above as this photograph was taken moments before the ball from the gentleman’s pitch was returned to his very feet. Such events weigh on the golfer the rest of the round, making No. 2 mentally taxing like few other courses.

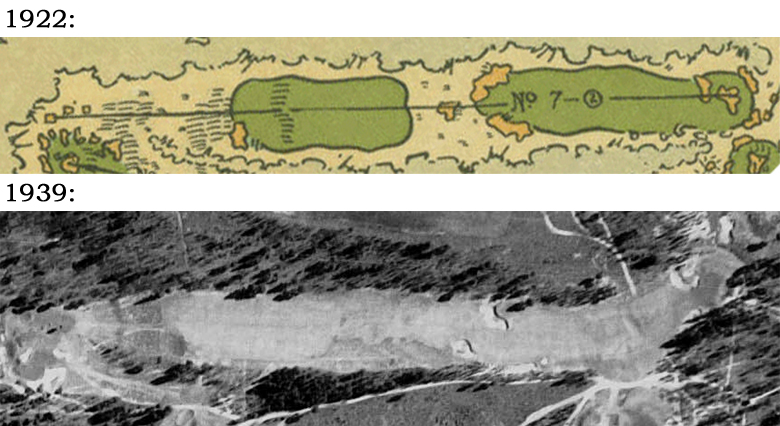

Seventh hole, 430/385 yards; Many restoration projects involve felling trees, recapturing numerous lost bunkers and expanding putting surfaces back to the edges of the green pads. Such was not the case with Coore & Crenshaw’s work. Indeed, the most significant design change to the course occured here at the seventh. Why? Because it was the most altered hole since Ross’s death. Richard Tufts had built up the seventh tee pad, added mounds to the outside of the dogleg and pinched in the fairway at its turn to a mere fourteen yards. Off the elevated tee, contestants during the 2008 U.S. Amateur were blowing tee shots over the trees on the inside of the dogleg and almost driving hole high. Coore & Crenshaw restored the hole’s compromised playing qualities.

Coore & Crenshaw built up the fairway bunker faces that protect the inside of the dogleg making them more penal hazards. Those trying to shorten the hole need to think twice.

This bunker sixty yards short of the green is one of eight Ross bunkers that was restored. Power hitters can no longer blow their tee shots over the corner of the dogleg with impunity.

Eighth hole 490/440 yards; Ross captured some of the most pleasant undulations on the property within this hole. All but the longest drivers play into a valley from where they face an uphill approach to one of the most built up green pads on the course. John Daly famously lost control to the left of this green during the 2005 U.S. Open. Having putted from off the green once too often for his satisfaction, he elected to hit a moving ball and was disqualified. A sad ending for a man with such a gifted short game but the banks that feed balls off the greens can elicit such frustration. A clip of John Daly is found on the Facebook page of GolfClubAtlas.com. Despite its length, the hole plays just fine as the green is open across its front and accepts a wide variety of approach shots.

Though a brute, the eighth rests peacefully upon the land, such was Ross’s talent for cutting bunkers into land forms and for building up green pads in order to present an attractive, yet challenging target. His ability to compliment nature shames almost all architects that have followed him in the greater Pinehurst/Southern Pines area.

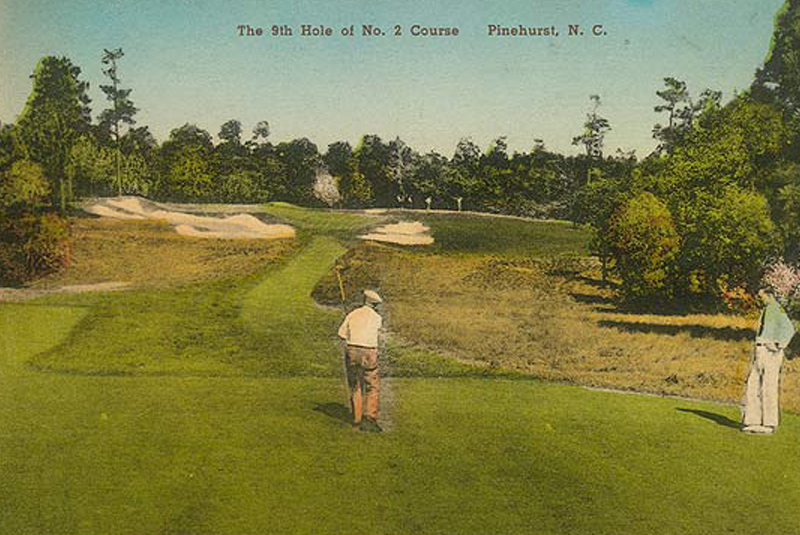

Ninth hole, 190/150 yards; The shortest hole on the course features the most heavily defended green. Set at an angle to the tee, the wide shallow green climbs from front right to back left with a distinct tier at its narrow waist. Similar to the seventeenth at Pebble Beach, the hole location makes a tremendous difference in how it plays. Those on the back flat plateau are difficult because the effective landing area is less than 700 (!) square feet. Front right hole locations are easier to access as the tier in the middle of the green feeds tee balls to them but conversely, the putts feature more break than on the flatter top tier. Though the green measures 6,011 square feet, only 1,880 square feet of it features 3% of slope or less. A very fine one shotter, deserving of recognition for its diversity without appearing contrived.

Today’s back left hole location requires a well struck iron to find and hold the small back plateau.

Just as he was in this postcard, Ross surely would be pleased as to how Pinehurst No.2 presents itself today.

Tenth hole, 620/460 yards; Architects like William Flynn, A.W. Tillinghast and Donald Ross believed in the importance of challenging the golfer with true three shot holes. As far back as 1923, this hole measured 540 yards which was no easy feat to cover with hickory shafts. Initially, the hole played straight ahead to a green located nearer the fourteenth green and featured a Sahara type bunker complex to be carried on one’s second. Subsequently, Ross came to believe that such hazards were too one dimensional as they don’t allow an alternate route for the weaker player. As part of his massive re-do in 1935 that saw the course grow to over 6,900 yards in length, the Sahara bunker complex was eliminated. Instead, Ross turned the tenth fairway to the left at the 125 yard mark from the green. Weaker players could bunt the ball along the fairway and still reach the green in three from a far forward set of tees while the tiger worked hard to properly position himself for a pitch to the green from the new 590 yard set of tees. This is yet another example of Ross attractively engaging all classes of players.

…it isn’t. Out of bounds threatens down the left while this mound down the right ensnares many a pushed tee ball.

The tenth fairway has pivoted left around this crossbunker for over seventy-five years.

Eleventh hole, 485/375 yards; The eleventh and twelfth occupy land near the harness track/polo field where the elevation varies only a few feet. Here is what’s interesting: Standing on the eleventh tee, the golfer who turns left sees prime golf terrain with holes flowing up and down over the attractively rolling land. This is the No. 4 Course which wraps past No. 2 at the eleventh and twelfth holes. Ross could have easily embedded these two flattish holes into the No.4 course if he was so inclined. That he didn’t and because these holes have been in continuous use since 1911 tells us that Ross liked what he accomplished here. Mo less than Ben Hogan numbered the eleventh among his favorite two shotters in golf.

Set across flat land, the carry to reach the fairway looks longer than it actually is. While the playing corridor is relatively straight, look at how today’s far right hole location creates what Max Behr referred to as a ‘line of instinct.’

This photograph of Hogan could well be taken today, such is the recaptured sandy floor of Pinehurst No. 2.

Twelfth hole, 450/360 yards; In contrast to the eleventh which offers clear sailing down the fairway’s middle, Coore & Crenshaw brought in a mound on the left that pinches the fairway to twenty-two yards at the 300 yard mark from the back tees. While a lay-up off the tee might seem prudent, that doesn’t answer the question of which side of the fairway. Time and time again, the challenge posed by No.2’s wide fairways is where ideally to place one’s tee shot. Here, the sight of the flag to the right suggests that the right portion is best. But is it?

No surprise to Coore & Crenshaw fans that they did a remarkable job in recapturing the rawer, more unkempt look that defined Pinehurst in Ross’s time.

Thirteenth hole, 385/360 yards; Ross determined early on that his routing would utilize a ridge line at the back of the famous practice area later dubbed Maniac Hill. He ultimately placed the thirteenth green and fourteenth tee on it with wonderful results. As charming as any hole in golf rich Pinehurst, the thirteenth’s green complex would fit perfectly at Holston Hills, where Ross did such a superb job of locating greens on top of hillocks. While the thirteenth may be short on length, it is long on playing qualities. The green’s false front has returned many approach shots back into the fairway as well as a putt or two! Only twenty-six yards deep, the 5,056 square foot green represents the shallowest target found among the two shot holes. Some modest length holes become easier the more they are played but not here where familiarity breeds respect, as well as less greedy playing tactics.

Ross got the maximum out of the distant ridge line when he placed the thirteenth green and fourteenth tee on it.

This golfer’s pitch shot hit six paces onto the green before spinning off. He now faces a ticklish recovery and will soon be soon left to wonder how he carded a five on a sub 400 yard hole.

Fourteenth hole, 480/420 yards; From its elevated tee, a fine view is afforded down the length of what many consider to be among the finest two shot holes anywhere. In Golf Has Never Failed Me, Ross recounts an interesting story. As he set about bunkering No.2, members began grumbling that the course was rapidly becoming too difficult. Pinehurst No. 1 was relatively free of bunkers and many felt that they would confine their play to the easier course. Within weeks however, all play had shifted to No.2 and according to Ross, ‘we were confronted with the problem of what regulations we could make to relieve the congestion resulting from the desertion of Number One.’ Ross opined ‘that a course bunkered fairly and scientifically is the most attractive’ and that golfers do indeed enjoy being challenged by hazards that are placed in a well thought out manner. Such is the case at the fourteenth with demands that never dull.

The left bunker that protrudes into the fairway in driving zone area shoves golfers to the right, from where the approach is over a deep bunker twenty yards shy of the putting surface. Even from this advantageous perspective, little can the golfer tell how well defended the fourteenth green actually is. Those who miss it long are shocked to find themselves below the level of the putting surface.

Sixteenth hole, 535/480 yards; Playing this hole as a par four in the 1999 and 2005 U.S. Opens was a mistake. Ross intended Pinehurst No. 2 like all his designs to be a course of give and take. The birdieable third and fourth holes precede the brutish fifth and sixth and the shortish thirteenth is followed by the tough fourteenth and fifteenth. Converting the sixteenth, one of Ross’s all time best par fives thanks to the interesting features found 100 yards short of the green, into a par four robs the course of the ebb and flow that Ross so carefully instilled. Hopefully, at least the women will play it as a par five during the 2014 U.S. Women’s Open so that eagle cheers might reverberate through the tall pines creating a thrilling finish. The late great Seve Ballesteros would concur about the unsettling effects of eagle roars versus those reserved for mere birdies.

Pinehurst No.2 has charmed golfers for decades in part because most golfers finish the round with the same ball with which they started. The sole water hazard on the course comes here at the sixteenth where Ross got it quickly out of the way.

This nest of the three bunkers 305 yards from the back markers catches tee balls that weren’t properly shaped into the angled fairway. They are a real menance when the fairways are fast and firm.

This low sliver of a bunker is not visible from back in the fairway as Ross didn’t build up its far bunker wall and instead had it follow the grade of the land. Its impact – and the uncertainty created by not seeing exactly where it is – looms large for those laying up.

Befitting a reachable par five, one of the course’s most penal bunkers is found at the right base of the green. Its serpentine configuration leaves many awkward recoveries to a green that is unique at No. 2 in that the putting surface is nestled down among its surrounds. The other green complexes are more starkly exposed and therefore more visually intimidating.

Seventeenth hole, 210/160 yards; Given how Ross built up his green pads, he was free to insure that they required all type shots without favoring one over another. Take the par threes as a set. The sixth enjoys a right to left Redan playing characteristic as the green slopes from front left to back right. The short ninth requires a precise aerial shot and the fifteenth is straightaway. Here at the seventeenth, Ross built a green that best accepts a fade, thereby completing a fine set of one shot holes that allows the golfer to show off his full repertoire.

In fine contrast with the sixth, Ross angled this green from front left to back right.

Eighteenth hole, 455/365 yards; Despite the modern lines of the low slung clubhouse roof in the background, the golfer feels an intense connection with the golfing greats that have gone before him as he heads up the Home fairway. Jones, Hogan, Snead, Nicklaus, Palmer, and Woods have all played here and expressed their admiration for this brand of golf. The irony is that none have come close to replicating it in their own golf design endeavors. Other courses down Midland Road feature rock-lined ponds and heavily shaped earth, none of which bears any resemblance to Ross’s work.

Ross cut the course’s most fiercesome fairway bunker into the upslope at the eighteenth and it now requires an uphill carry of over 260 yards from the back markers.

Pinehurst’s place in history is secure. It is capable at a moment’s notice of hosting events such as the Ryder Cup and U.S. Open. Rough doesn’t need to be grown as there is none. All the course needs to test the best is fast and true playing conditions. The short grass that feeds balls into well placed bunkers or up – then off – these diabolical greens provides an ample challenge just as it has for decades. In the first half of the twentieth century, No.2 played host to one of the most prestigious events that the PGA Tour has ever conducted, the North and South Open.

Here is what Dan Jenkins had to say:‘For many years, the old North and South Open on No. 2 was sort of a Masters before there was a Masters. Touring pros and golfing enthusiasts alike remember the North-South and Pinehurst as the tour’s annual brush with charm and elegance. Black tie and evening gowns for dinner. Eventually, it was the favorite tournament of Ben Hogan and Sam Snead, who each won it three times and in fact considered it a major as did the equipment and apparel companies who gave bonuses to the North-South winner just as they did for the winners of the U.S. Open, PGA and Western Open.’ What is so impressive about this design, and what makes it virtually unique with The Old Course, is that the next day after hosting such events, a family can enjoy the course too.

Providing maximum fun and challenge to the broadest range of golfers possible is surely the epitome of great golf course architecture. At Pinehurst No.2, it didn’t occur overnight but was very much an evolutionary process. While holes 11-18 have been in play since 1911, holes 3 and 6 were created in 1923, holes 4 and 5 were added in 1935, and Ross converted all the greens from sand to grass in 1935. The success of these transitions – unlike virtually every other great course save for Myopia Hunt and the National Golf Links of America – is that the same man who originally designed the course oversaw all modifications. Thus, Pinehurst No. 2 epitomizes even today a course with a consistent, unified feel. To properly appreciate the evolution of Ross’s masterpiece as well as golf in Pinehurst, be sure to purchase a copy of Richard Mandell’s book entitled Pinehurst – Home of American Golf. It is available in the Pinehurst golf professional shop.

Shortly after finishing the overhaul of Pinehurst No.2 in 1935, Ross penned these telling words that provide great insight into his intent as an architect: ‘Bearing in mind that golf should be a pleasure and not a penance, it has always been my thought to present a test of the player’s game; the severity of the test to be in direct ratio with his ability as a player. I carried out this thought in the changes made on Number Two. I am firmly of the opinion that the leading professionals and golfers of every caliber, for many years to come, will find in the Number Two Course the fairest yet most exacting test of their game, and yet a test from which they will always derive the maximum amount of pleasure. This, to my mind, should be the ideal of all golf courses.’

His words ring as true today as they did then and for that, we can all be thankful that Pinehurst is once again a beacon for all that is good about the game of golf.

The End

![The Park, West Palm (Lit 9) [2023]](https://golfclubatlas.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_7092-2-scaled-500x383.jpg)